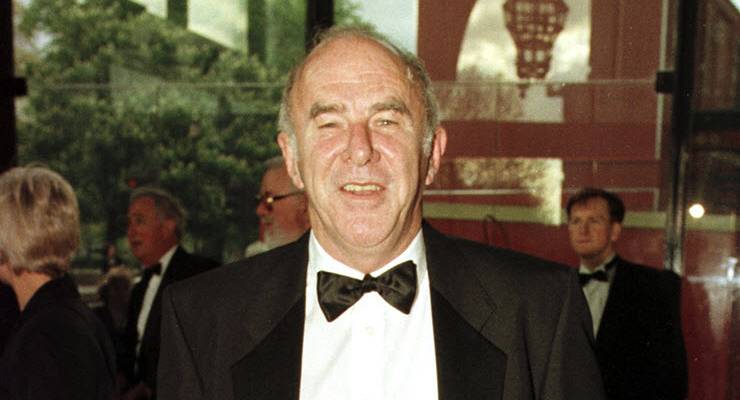

Goddammit, Clive James. The man spends a decade not dying of an allegedly rapid terminal illness, and then shuffles off while half a dozen other things are going on. This august publication should probably observe the practice of writing its obituaries ahead of time, but we don’t so ehhhhh, this will not be a full consideration of Vivian Leopold James, simply a first reaction.

Call it a prelimbituary, an amuse mort. The man wrote 40 books, and one imagines there are more to come, from diverse sources. He deserves a bit more consideration than can be given in a morning.

And he deserves it for two reasons. The first is that most of the immediate notices will be of the higher boilerplate variety, brilliant this, brilliant that, of the Aussie generation that, Germs, Robert, Barry, etc, etc, all of which will sound like the memorial of a senior military figure whose life works and motivations his obituarists do not understand, but who was, in the end, so garlanded with honours that his importance cannot be denied.

So it is for a writer in the public eye for decades, whose recent works included a long narrative poem, and a collection of his essays and reviews of the poet Philip Larkin, all put out, and commercially pushed by his faithful publisher Picador. The result was a paradox: Clive James became the poet for people who don’t read any other poetry, the critic for people who wouldn’t even know where to find other literary criticism. Truly assessing his legacy means getting beyond the catalogue of honours of a man who had got himself a pretty unique deal in Anglosphere publishing.

The second reason, for this writer at least, and I suspect I am far from the only one, is that, in my lifetime, my view of James has swung from his work being — to quote Peter Corris’ review of him in the old National Times— “the reason God gave you eyeballs”, to finding it so irritating, smug, rote and frequently fatuous that I recognise it as an irrational reaction, but can’t do anything about it.

His translation of Dante’s Commedia, which managed to be worse than Dorothy L. Sayers rhymed version from the 1920s, the essays in Cultural Amnesia, where a piece on a French film essayist is liable to veer off into a defence of John Howard’s border policy, the volume of memoirs dealing with the TV years from which all the wit and self-deprecation of the early volumes had been excised in service to the legend that he was now a great thinker on the media — these seemed to get good reviews. Some of them were by people I respected, yet every time I picked one up, all I felt was the disappointment with someone whose writings I once couldn’t get enough of.

A Clive James book once cost me a friendship. I was 18, had a job as a dishwasher in a busy restaurant, was enjoying the pleasure of buying stuff with hard-won wages. I’d picked up a second volume of his TV criticism from the ’70s, having randomly encountered the first, and felt a pure surge of pleasure and revelation at what was a sort of metropolitan cultural studies: pitch-perfect appreciation of ’70s sci-fi kitsch such as the Martian Chronicles (“have you checked the gyroscope?”), full-length reviews of Wimbledon when rain stopped play, and commentators had to fill with updates on the winding out of the tarpaulin, etc. You could do this? Apparently you could.

Waiting for a late train at Flinders St, just starting what would be a delicious, an essential, 40-minute read, I saw D come down the platform ramp — and he saw me, and my look of utter dismay, impossible to revoke, that I would now not get to read Clive, and that boring, stilted, hurt conversation was the last time D and I ever spoke. And, to be honest, I cared more that I hadn’t got to read Clive James.

That was how much Clive meant to me once. So there was good Clive and bad Clive. Or was there? Going back to the early stuff a couple of years ago — which I wish I hadn’t — the TV criticism, the early lit crit in At the Pillars of Hercules, the first two volumes of memoirs, it all seems so, my god, the only word is jejune.

Why does the TV criticism spend so much time talking about the USSR and the Holocaust? Why does the lit crit veer so often into cod summaries of Wittgenstein? Why is Falling Towards England stuck together with so many cheap one-liners, like a nervous stand-up comic who makes the audience more anxious rather than relaxed the longer he goes on?

I couldn’t get enough of the stuff when I was 18, but I was 18. What do actual adults see in it? Did I overdose on it? What went wrong? Was it Clive’s public persona, which suddenly became pompous and pronouncing, as if he were an actual scholar? Was it his asinine denialist pieces on climate change, which revealed that, after all, he really might not be too bright? Was it that voice, that ridiculous where-was-it-from, mid-Atlantic brogue, an Australian in Britain trying to sound like an American, that seemed to confirm Auberon Waugh’s judgement of him, both snobbish and accurate, that he was a “cringing man on the make”?

What can you say about a man who says of his own poetry that “it sounds like reproduction furniture looks”, and who then keeps on writing it, for decades more? God knows, god knows. But his work deserves some more thinking on than the sum total of my irritations, focused to a point by the announcement of his demise.

In the mainstream press, the shilling lives will give you all the facts. Here, let’s see how Clive James looks a bit later, now that he’s no longer around to get in the way of himself. We are not done with you yet, but vale Clive James.

Send your memories of Clive James to boss@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication.

Best tribute to Clive James must be Jeffrey Smart’s portrait of him which consists mainly of a yellow corrugated iron fence, with a tiny figure leaning over a bridge in the distance.

Nice summary GR though you obviously knew more about him than me. I really enjoyed his auto bio of a struggling horny expat trying to get work and a root in a cold grimy England.

The tv stuff was often good but became formulaic and all those other words you used. A wordy tonight show Third Ronnie.

Didn’t know about the poetry and CC denialism by otherwise smart people is one of the most bizarrely fascinating conundrums of our age.

My father had the same two reactions (decades apart) as Guy did. In his case the author was G.K. Chesterton, not so accomplished a poet.

For my part I first noticed him through his tv shows in which he crawled (sorry pandered) to his English audience by sneering at the Japanese. As you learn in high school the easiest way to avoid being bullied is to get in first by picking on the nearest scapegoat.

Let his eulogy be the one delivered by the Headmaster in The History Boys.

“He loved words.”

I dont think ‘sneered’ is fair. He used his tv shows to feature tv from elsewhere that looked weird to us. It was fun, though others (and he, maybe) overclaimed – kenny everett was the true pioneer

Not half as much fun as “Mourning my friend, Princess Diana”. Is it too much to hope for a few words from Prince Andrew?

As usual Rundle doesn’t pull his punches & it’s hard to disagree with this assessment. On reading the translation of Dante’s Commedia, an Italian pal was so dismayed that he spent a couple years writing his own version in order to expunge Clive’s from memory.

However, his talk show, The Late Clive James, was often premium viewing. Check out some of the old interviews on Youtube, especially those with satirists Peter Cook & Barry Humphries, both of whom appear to relish the exercise.

Ditto

From his early work which I read avidly, laughed at ,and once even bought in hard back,

how did he get to his far later ABC radio series in which Clive and some other bloke talked over the top of each other on mightily obscure topics in a sort of erudition version of “It’s a Knockout?