This article first appeared in John Menadue’s Pearls and Irritations.

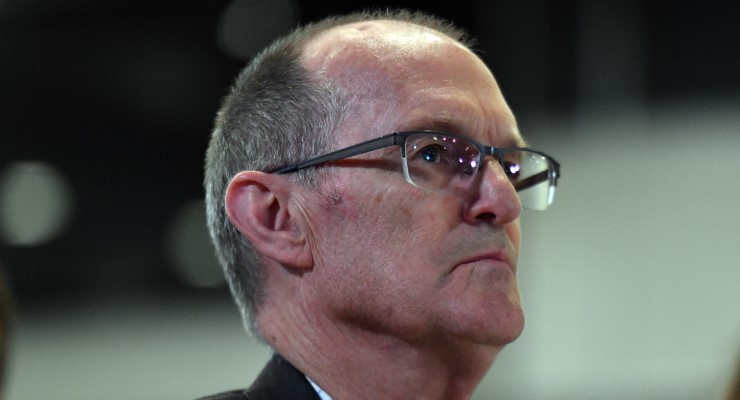

The report by the secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet Phil Gaetjens into Bridget McKenzies’ handling of the Community Sport Infrastructure grants fails to address key questions and raises serious concerns about the relationship between the government and the public service.

For a start the Gaetjens’ report should have been publicly released so that we could all satisfy ourselves that justice had been done.

A secret trial where the evidence considered and the reasons for the judgement are not released does not satisfy any standard of accountability.

However, the minister, Bridget McKenzie, has now resigned from cabinet — on what she appears to regard as a technicality — and the government would clearly like us all to now move on and forget this incident.

Nevertheless, we should continue to be concerned by Gaetjen’s finding of not guilty to the more substantive charge by the auditor general that “There was bias in the award of grant funding … [which] was not consistent with assessed merit of applications”.

The key evidence cited by the auditor general was that just over half the grants approved by the minister were not recommended by Sport Australia. In effect, the Minister ignored the assessment by Sports Australia against the known criteria, and instead the auditor general found that:

The award of funding reflected the approach documented by the minister’s office of focussing on ‘marginal’ electorates held by the Coalition as well as those electorates held by other parties or independent members that were ‘targeted’ by the Coalition at the 2019 election. Applications from projects located in those electorates were more successful in being awarded funding than if the funding was allocated on the basis of merit against the published program guidelines.

On the other hand, according to the prime minister, Gaetjens allegedly found that “the data indicates applications from marginal or targeted seats were approved by the minister at a statistically similar ratio of 32% compared the number of other applications from other electorates at 36%”.

And on this evidence Gaetjens allegedly found “no basis for the suggestion that political considerations were the primary determining factor”.

Frankly I find these (unsubstantiated) findings by Gaetjens difficult to reconcile statistically with the evidence produced by the auditor general.

For Gaetjens to be right, applications from the marginal and targeted electorates would have had to run at double the overall rate to be consistent with the eventual electoral distribution of the grants. Of course, any such presumed bias in the application rates beggars belief and I query the government’s defence on these grounds.

However, the other line of defence by the minister and the government is that she had the right to use her discretion and determine her own allocation of these grants, irrespective of any criteria and assessment against those criteria.

No-one denies that ministers should have discretion; it is they who are elected, not public servants. Nevertheless, as David Solomon pointed out, ministers are bound by a code of conduct in the exercise of their ministerial discretion.

That code requires them to act with due regard for the integrity, fairness, accountability, responsibility and the public interest.

In relation to grants programs, compliance with the code of conduct usually means ministerial discretion is limited to ministers determining the criteria for assistance, but not deciding which individual applications most merit assistance.

In any event, reasons must be given and documented for how ministers exercised their discretion.

Indeed, some may remember that it was Ros Kelly’s inability to produce documentation of her reasons that led to a negative finding by a House of Representatives committee, and Kelly losing her job as the minister responsible for a similar sports grants program 27 years ago.

Thus, the obvious question that the Gaetjens’ report should have addressed is: what is different this time?

If McKenzies’ department had been responsible for administering this Sports grants program, then she would have had to abide by the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines (CRGGs).

In that case McKenzie would have had to use criteria that established merit in the same way as Sports Australia did in conducting their assessment for their recommended allocation of these grants.

Furthermore, the government has now accepted the recommendation by the auditor general that the present exceptions should be removed and that in future all programs should be bound by the CRGGs.

But that seems to be tantamount to admitting that McKenzie should have been bound by these rules this time too. So the fact that she got off on this unfortunate technicality doesn’t excuse her ethically for not following the code of conduct.

So, where does this leave us in relation to the Gaetjens’ report?

Personally, having also been the secretary of the prime minister’s department and cabinet, and having been involved in a similar situation, I find the fact that Gaetjens’ report apparently ignored these fundamental considerations of good government and ministerial conduct inconceivable.

In my view the Gaetjens’ report reflects poorly on its author.

It would seem on the evidence that Gaetjens has produced a report whose only purpose was to get the government off a political hook.

One suspects that finding McKenzie guilty on the grounds of political bias in her administration of these grants would have implicated other ministers and/or their offices, and therefore she was exonerated on this charge.

However, as head of the public service, Gaetjen’s first duty is to uphold its values and integrity. And as set out in its enabling legislation, the Australian Public Service is meant to be apolitical, serving not only the government but also parliament and the Australian public.

Gaetjens should be setting an example for the rest of the APS — indeed the head of any organisation has their greatest impact on its culture.

My other concern about this sports rorts saga is what it tells us about the prime minister’s attitude to the public service.

As the High Court has found: “the maintenance and protection of an apolitical and professional public service is a significant purpose consistent with the system of representative and responsible government mandated by the constitution”.

But the Gaetjens’ report reinforces doubts about whether Morrison accepts the independence and impartiality of the APS.

Furthermore, this report comes on the back of the Morrison government’s rejection of all the recommendations from the independent Thodey Review of the APS which would have strengthened that independence, and therefore reinforces that concern.

In contrast, John Howard said in his 1997 Garran Oration:

Let me say at the outset my firm belief that an accountable, non-partisan and professional public service which responds creatively to the changing roles and demands of government is a great national asset. Preserving its value and nurturing its innovation is a priority of this government.

The responsibility of any government must be to pass onto its successor a public service which is better able to meet the challenges of its time than the one it inherited.

On the evidence of the last few months, Scott Morrison has failed to live up to his mentor’s precepts — indeed, he seems to positively reject them.

Michael Keating is a former head of the Departments of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Finance, and Employment and Industrial Relations. He is presently a Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University. This article first appeared in John Menadue’s Pearls and Irritations.

So we need someone to leak the Gaetjen’s report.

Appoint a one-eyed dog to watch the junk-yard, expect one side to go missing.

Howard’s professed precepts to Howard’s reality? You’d need a few Mackinac Bridges to bridge that gap.

One of the reasons for Howard’s enduring success was that his rhetoric was extremely effective in reassuring people and giving them what they wanted to hear.

Of course it was all completely cynical and calculated and his actions betrayed an entirely different set of values and priorities, but hey, he sounded so sincere when he said all these nice things so hordes of people lapped it right up.

There must be a slight chance that Gaetjen himself may be decent, and his report honest, and that Scotty either cherry-picked (at best) or outright lied (at worst) about the contents…we all know that Scotty is quite partial to a bit of bald-faced lying.

Either Phil or someone from the department should blow the whistle with a public copy of the report, and thus distance themselves from the governments illegal and unconstitutional stench.

What odds a Morrison/Liberal apparatchik being/doing that?

What odds that Morrison is not letting a copy of Gaetjens’ report go anywhere near the Home Affairs Minister’s Office.

What odds that Dutton doesn’t have a tame hacker on staff?

“…so that we could all satisfy ourselves that justice had been done.”

Witness K, Bernard Collaery, an unnamed prisoner held in the ACT prison after a secret trial. There is no longer justice – there is simply whatever the government wants to do and it shoves any critics before closed courts.

It is breathtakingly outrageous – and few Australians seem to care.

Both the major parties have colluded in those cases, so let’s elect the Greens. Of course if we do that, the USA will interfere. Again.