They should kill her kids and give her one of their livers. Then keep the other for when she inevitably needs a third.

One of the most affecting parts of Wild Butterfly — a dramatised documentary that chronicles Perth mother of two Claire Murray’s life, brief notoriety and death — is when it revisits some of the anonymous bile that collected under every discussion of her on social media.

The above quote is the worst, but not by much.

Murray had been a heroin addict when her liver failed. She relapsed after her first transplant, and the new liver developed blood clots.

Because of her drug use, she was told she could not be considered for another transplant. She was given three to six months to live.

***

Michael Murray, Claire’s father, was surprised as his family pulled up to the Parliament of Western Australia in February 2010 to see a cluster of journalists waiting for them.

The Murray family was there to discuss with MPs what might be done for Claire.

The next day, the story was on the front page of The West Australian.

“From that day on, the media were phoning everyday,” Michael told Crikey. “Myself, my wife at the time, my two other children, uncles, aunts, brothers, sisters, everyone. There were journalists that were parked outside the house for days.”

The vans were outside the houses of the Murray extended family. Initially, the family engaged with the media, thinking it would foster public support.

“We were pouring our hearts out to these people, they would give us the impression it was going to be from a place of sympathy, and then we’d see it in print and it would be the opposite,” Michael said.

The family eventually received an interest-free $250,000 loan from the state government to assist with arrangements they had made to visit Singapore for a second operation.

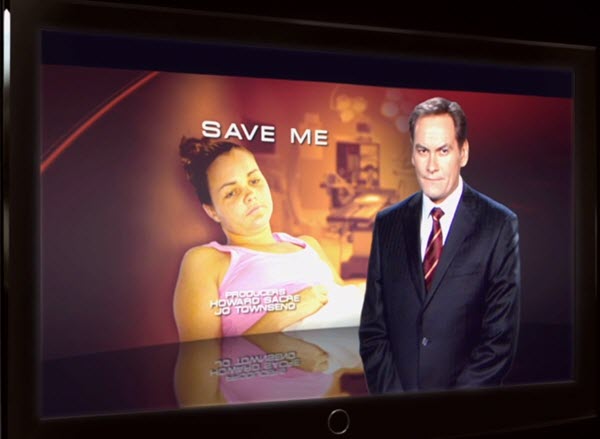

“Then it just went crazy. 60 Minutes got involved, the radio got involved, the TV stations got involved.”

“It wasn’t a nice place to be. We were going through …” Michael pauses for a long time. “We were trying to save our daughter’s life.”

The West held a poll asking if Murray should receive a second liver. “Which to me,” Claire’s mother Val says in the film, “was asking, ‘do you think she deserves to live or die’?”

76% of respondents voted that she did not deserve another liver.

60 Minutes paid to accompany the family to Singapore. Their reporter, Liam Bartlett, sat by Claire’s hospital bed and said “the fact is, you’ve brought this on yourself. You’re a junkie. Do you deserve a second chance?”

In a resulting piece, he wrote:

As tragically sad as all this sounds, and it is, I don’t expect you to feel sorry for Claire Murray.

To be brutally frank, having spent time at her bedside, I find it extremely difficult to like her at all. But here’s the redeeming thing — Claire doesn’t expect it …

This is a young woman, a heroin addict, who admits it’s her fault and nobody else’s that she finds herself in this invidious position.

“With 60 Minutes, we were believing there was going to be a bit of sympathy,” Michael recalls. “And it was quite the opposite.”

Bartlett — who was not approached to participate in the film — told Crikey he hadn’t seen it and thus “it would be foolish and ignorant to comment on its content”.

He said he stood by the 60 Minutes story “fully”.

Claire Murray died in April 2010, in a Singapore hospital, after complications resulting from the second operation. She was 25 years old.

“There were a couple of journalists who hung around after that, who I knew, who asked questions, but we didn’t give out any more information,” Michael said. “We learnt our lesson.”

“Claire could have been anyone’s daughter,” the film’s director Shireen Narayanan said. “And because of the way it played out in the media, it shows how deeply embedded the societal stigma around drug use really is.”

Despite the intervening decade, she said this remained a problem.

“I think in so many ways — say around mental health issues, or sexual assault — reporting standards have improved. But when talking about drug use … there are still really significant issues.”

Professor Steve Allsop of the National Drug Research Institute told Crikey media treatment like that which Claire Murray received has effects beyond the individuals concerned.

“Dehumanising language like ‘junkie’ means people think ‘oh I’m not like that’ and don’t seek help if they’re at risk,” he said.

“Or they don’t seek help because they think they’re going to be judged. So it effects prevention and treatment outcomes.”

Allsop said this societal stigma — most recently expressed through drug testing for welfare recipients — was part of the reason drug and alcohol services remained chronically underfunded.

More than 100,000 Australians seek treatment for drug dependence every year. It is estimated that only about half of those people receive adequate treatment.

For all the words written and broadcast about her, huge parts of Claire’s story were elided.

When she was 12, Claire was raped at a school camp. As Narayanan puts it, as much as the story is about a media pile on, Wild Butterfly is also about an unsolved crime. The case was re-opened in 2016 after four years of lobbying from Val and Michael.

The film chronicles a series of systemic failures that followed; the response of Claire’s school, a series of misdiagnoses regarding her worsening mental health, and allegedly missed medical information that might have saved her.

“Piecing this together, it became clear Claire’s story was an incredible snapshot of systemic failure across the board,” Narayanan said.

Wild Butterfly is an attempt to return to Claire a humanity that was taken from her, time and time again, by individuals and institutions. It is, at times, an unbearably harrowing film.

“I don’t just want to single out the journalists, there were mistakes all the way along,” Michael said.

“Hopefully the movie makes some positive changes, so we don’t see another Claire Murray.”

Wild Butterfly is showing in select cinemas around Australia. For screening times, go here.

For anyone seeking help, Lifeline is on 13 11 14 and Beyond Blue is 1300 22 4636. If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault or violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au.

A timely reminder of the flip side of media freedom. I can marvel on the one hand at the family’s gullibility in expecting anything but the worst from a tabloid tv show while at the same time feeling great sympathy.

Ordinary people should not need to be wary of media exploitation and mistreatment at times of crisis. I’ve never heard of an industry commitment to reform or self regulate these issues. Get this fixed and you’ll find a lot more people interested in protecting media freedom from mendacious political control.

Frontline is as relevant as ever.

“We were trying to save our daughter”.

Sweet Jesus.

How can anyone with a pulse deny the simple validity of a feeling like that?

I don’t get people.

The story is almost always the same.

Firstly a pubescent or pre-pubescent child is sexually assaulted, usually by someone they trust.

If the report the abuse, then comes the stigma……… then they go off the rails.

If they don’t report it, then most children go off the rails………

The majority of “Drug Addicts have a life history like this”.

If the media do not know this, then their education has been lacking.

Claire was lucky that she had people who cared for her and about her.

I don’t watch 60 minutes because of the trashy judgmental attitude portrayed.

Unfortunately, as a reporter, Liam Bartlett allowed his personal judgment to interfere with his objectivity and as such is perfectly fitted to work on 60 minutes forever.

Yeah, heartless and mindless journalism from where you’d expect to find it.

And the craven cowardly public pile on.

We are an awful people.