The Australian Hubei Chamber of Commerce and the Hubei Association of Melbourne are probably best known for their association with “junket” operators, ferrying high-roller VIPs between Wuhan and Melbourne’s Crown Casino.

They are also known around town for gala events and sponsorship of cultural performances, including the PLA-inspired musical Red Guards on Honghu Lake performed in Melbourne in 2018.

Less well known is their capacity for charitable fundraising and getting things done for a good purpose.

Stirred by graphic stories on Chinese social media of hospital staff in Wuhan struggling to deal with the coronavirus epidemic, local members launched a new round of fundraising to help medical teams in Wuhan.

Within a few weeks of Beijing acknowledging the outbreak, they had teamed up with other associations and private firms to raise more than $200,000.

Then the problems began.

It was not just that the city of Wuhan was in lockdown, or that Australia had imposed strict travel bans, or even that commercial airlines were cancelling flights by the hour.

The reality is, Wuhan had little capacity at the best of times to handle charitable donations. The bureaucratic hurdles in the way of cross-border donations presented further headaches.

In China, party and government officials dominate official charity distribution networks. They assume the right to take a substantial cut for their own expenses, and often hand over donations to party and government cadres rather than passing them on to the people for whom they were intended.

Faced with the outbreak of the coronavirus, the national Ministry of Civil Affairs identified five party-managed charities to handle donations from outside Hubei province, including the Wuhan Charity Federation and the Wuhan Red Cross. It ruled out participation by other charities and non-party civic groups.

From my experience, people in China feel that official charities cannot be trusted with money. In this case they were right to be doubtful.

By mid-February, the Wuhan Charity Federation had received around 3 billion yuan– more than A$658 million — in donations. It then extracted $65 million for its own administrative expenses before transferring the remainder to the local government to manage.

Donors vented their anger on social media about their private generosity being converted into another revenue source for government.

Experts were of the same mind. Charity specialist Jia Xijin of Tsinghua University in Beijing said the Wuhan charity should have distributed the funds itself instead of handing them over to government: “This is not the correct way for a social organisation to do its job … [it] essentially makes them tax collectors [for the government].”

So there was no question of sending money directly from Melbourne to Wuhan.

And yet donations in kind were faring little better. Chinese social media was awash with stories and photos of donated goods piling up in charity warehouses in Wuhan. Early in February, the local Red Cross acknowledged the problem and conceded that donors could bypass official charity distribution networks and deliver supplies directly to hospitals.

It’s then that a number of stories started to emerge about donors and charities bypassing official channels and delivering aid directly to preferred hospitals. The Melbourne Hubei initiative was one of them.

For the Melbourne-based Hubei associations it helped that a small team of public health specialists at La Trobe University was already planning to purchase and forward a large consignment of needed medical supplies to hospitals in Wuhan.

At that time the La Trobe team still needed to identify appropriate equipment, find suppliers, and one way or another ship the goods directly to hospitals in Wuhan. They had no money either. But they had the expertise and the connections.

A teacher of health services management at La Trobe University, Dr Zhanming (Ming) Liang, knew some of the doctors on the front lines in Hubei who had been transferred from a hospital based in another province, Shandong, where she had spent time working. She reached out to the hospital.

Ming also called on the support of a friend who had studied in Wuhan, Shawn Lin. She identified and sourced equipment and worked with another health management specialist at La Trobe who put her in touch with Wuhan native Jie Fang and the Hubei Chamber of Commerce.

The Hubei associations had been talking about of raising funds but had no idea what to do with the money.

The obstacles were formidable. By all accounts it was the persistence of the two women, Ming from La Trobe and Jie Fang, a successful businesswomen from Hubei, that made the difference.

Ming had the idea and the expertise and pulled the team together. Jie Fang raised the funds, contacted airlines, and got in touch with hospital managers in Hubei.

She also managed the logistics including securing approvals, getting the equipment up to Sydney and onto the flight, and finally on the ground in China where she found people who could deliver the supplies to the target hospitals.

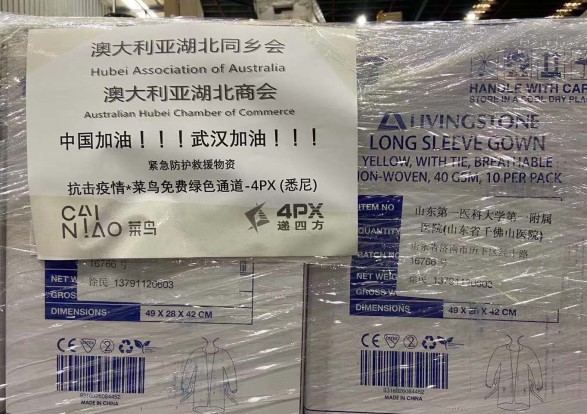

Less than a month after Ming launched her initiative, almost five tonnes of medical supplies including 100,000 pairs of gloves, 20,000 isolation gowns, and 2100 face shields and masks were bundled into pallets and shipped directly to eight hospitals in and around Wuhan and Shandong.

Macquarie University historian Dr Mei-fen Kuo researches the role of women in old-style male-dominated community associations in Australia, particularly their charitable activities.

“Women leaders are transformative,” she told me. “They make things happen in ways the old brotherhoods just can’t match.”

Great story, Professor. I hope these two get the commendation they deserve both here and in China.

Except, we need a good deal of what the Latrobe team extracted a little closer to home. I admire the spirit, but not the source of the supplies.

So now they have helped to solve the crisis in Wuhan, what about organising to get some of those supplies, hoovered up from Australia, back here to help. I understand the priorities – now it’s the time for reciprocation.

My sentiments exactly, PG! We are hearing every day about shortages of these items in Australian hospitals…I even know of one instance where thousands of masks were stolen from a Melbourne hospital ED.

So…NO, I don’t think this whole exercise is praiseworthy. It should never have been allowed to happen.

A warm and wonderful gesture, on a par with that of property developers Greenland and Risland, as sen in SMH, (and who knows who else?).

Little problem though – no wonder we’re now short of protective gear.

It seems the buy-out of medical supplies such as masks and hand-sanitisers was happening in other countries as well, and all at the instigation of the CCP authorities.

Watch the first 3 min of this to see what was happening in elsewhere.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OkBYeKAsbxg

Cutting red tape? Not much tape would have been needed to cut to get those masks into China.