The story is 6000 years old, but without world-first digital projection technology and a new funding model that turns traditional arts sponsors on their head, it simply couldn’t be told.

Yabarra: Dreaming in Light, the immersive cultural experience that has become a breakout hit at this year’s Adelaide Fringe Festival, is an ancient story told in a very modern way.

And after the fringe turned an initial $150,000 state government grant into a $1 million multilayered Dreamtime story, it is destined to have a profound impact on future cultural presentations of Indigenous stories across the nation — not just in how they are created, but how they are funded.

Just this week, members of the Australia Council, the country’s peak arts-funding body, were given a guided tour of the digital animated light installation.

The walkthrough transports audiences through the story of how Tjirbruki, overwhelmed by the grief of his favourite nephew’s death, decides he can no longer live as a man and ascends to the heavens.

After being roundly rejected by traditional national grant bodies, the Fringe was able to turn Yabarra into reality thanks to eschewing traditional funding and sponsorship methods in favour of the process of co-creation.

The process was made easier by the fact that, in South Australia, the minister for Aboriginal affairs, tourism, and the arts are all the same person, Premier Steven Marshall.

And it was also possible due to the power of the Adelaide Fringe Festival, the nation’s largest cultural event, which last year sold more than 800,000 tickets and scored a $19.4 million box office.

The fringe, as commissioner, presenter and fundraiser, gathered together artists and producers — such as Aboriginal Arts collective Yellaka and digital creators Monkeystack — as well as sponsors and technology companies, when the project’s ultimate form was still unclear.

The fringe scrapped its annual street parade in the desire to do something different, and create an Indigenous arts hub around Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute, Australia’s oldest Indigenous cultural institute.

The state government gave an additional $100,000 as an artists’ grant to create a First Nations cultural program for the festival.

“Everyone is at the table equally,” said fringe director and chief executive Heather Croall. “The best of Indigenous storytelling, the best of technology, the best of immersive storytelling.

“The power of co-creation means it is not all signed off and not everyone knows what they are doing. There is a much higher level of uncertainty but it can create something way bigger. It could become a model for creating art, but it would take a lot to get big funding organisations to shift.”

The depth of technology used throughout project is striking. Tjirbruki is brought to vivid life by the world’s first folded, two-axial rotatable lens, which allows for continuous ceiling and wall projection. There are 36 projectors, 29 intelligent lighting fixtures, 684 kilograms of velvet drapes, smoke machines, low-fog machines, a hazer and a custom built indoor tornado.

“It is a lifechanging experience going through Yabarra, people’s hearts open, people’s minds open,” said Croall. “You can’t leave without wanting to know more.”

Yabarra is also the story of Kaurna Senior Woman Aunty Georgina Williams, who in the 1970s helped to reawaken the ancient tale and fought to keep history alive.

“The thinking about the story and mapping it has been going on for quite some 6000 years. We have just been waiting for the technology to catch up really,” said Karl “Winda” Telfer, creative cultural producer of Yabarra and Senior Kaurna Custodian.

Old wisdom. New ways. “The technology has been really important to pull all generations in, to look in a different way and understand and reflect on that,” said Telfer, who is Williams’ son.

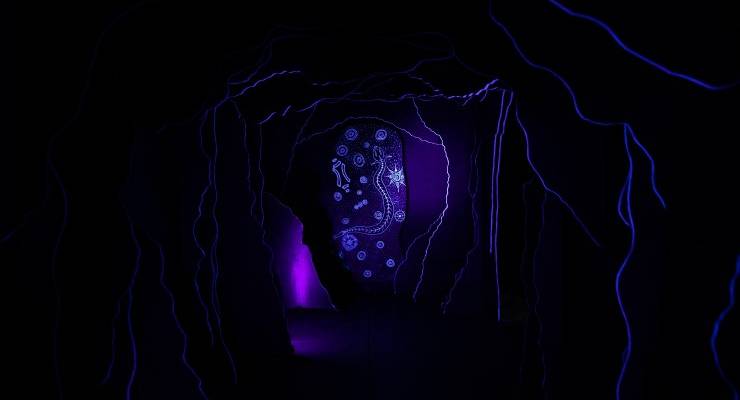

As audiences enter, an illuminated campfire sets the scene, before yellow footsteps lead visitors onwards. Overhead animals glide through the milky way, the river of ancestors.

Spirit trees dot the landscape while animations slowly transform rock faces into the face of Tjirbruki, who, overwhelmed by the killing of his favourite nephew, sheds tears that cascade down a weeping rock, creating a fresh water spring.

An inscription urges calm, slow observance of the unfolding story: “Learnings come from patience, teaching comes from knowing and seeing comes from respectfully waiting to understand.”

The message was one Premier Steven Marshall seemed eager to share.

“The premier has been in there about eight times, he keeps taking people down,” Telfer says.

Marshall’s government reflected that support with its total grants of $250,000 towards Yabarra and the Tandanya First Nations Hub at the Adelaide Fringe.

“Yabarra is a new way of telling an ancient story. A world class offering that deserves to be shown overseas,” Marshall said of the project.

The experience runs until 10pm each night and is crowded with school children, festival regulars, tourists and even motorsport fans attending the nearby Clipsal 500.

“We are spreading the ideas across different understandings of culture,” Telfer says.

The ancient creation story is specific to the Adelaide plains region, but echoes of such stories can be found across the country and around the globe.

In the farthest chamber of the walk, Tjirbruki decides to no longer live as a man and transforms into an ibis and ascends via a spirit wind — depicted as an artificial indoor tornado.

Thunder and lightning streak across the chamber. The sound causes a young girl in our walk to flinch, until she and her mates dance around in the smoke column that spins into a twister up into the ceiling, symbolising the ascension of Tjirbruki.

“People are just overwhelmed,” Telfer said. “Those sorts of interactions are priceless in terms of understanding cultural stories and First Nation peoples.”

Adelaide Fringe runs until March 15. The author travelled with the assistance of the fringe.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.