The claim

At the height of Australia’s recent bushfire crisis, Liberal backbencher Craig Kelly made the rounds of national and international media outlets.

In a combative exchange with meteorologist Laura Tobin on ITV’s Good Morning Britain, Kelly argued against the long-term drying out of the Australian landscape.

Tobin said: “Australia have just had, in 2019, their highest year temperature-wise ever recorded and their driest year ever recorded, with forecasts and temperatures that go back over 100 years.”

Kelly responded: “There’s a few issues there. Firstly, the first 20 years of this century we’ve had more rainfall in Australia than [over] the first 20 years of the last century”.

He expanded on the claim on his Facebook page, writing:

As climate scientists acknowledge, and anyone that can read a graph understands — although there are regional variations, across a [sic] 120 years of data, as Co2 has increased there has been no nationwide drying trend.

So, has Australia had more rainfall this century, compared to the first 20 years of the last century? And does the data show there is no nationwide drying trend?

RMIT ABC Fact Check investigates.

The verdict

Kelly’s claim is flawed.

Data collected by the Bureau of Meteorology shows an increase in Australia’s annual average rainfall for the first two decades of this century compared to the years 1900 to 1919.

However, experts contacted by Fact Check said this was a flawed means of assessing rainfall patterns and drying trends overall in view of Australia’s vast landscape and the high variability in rainfall behaviour.

They said the national average disguised regional differences, which were most starkly felt between the north and the south of the continent.

On average, northern Australia has become wetter but parts of southern Australia — namely the south-east and south-west — have become much drier in recent decades.

Further, less rain has been falling in the cooler months in the south, a period critical for streamflows, water storage and agriculture.

Experts told Fact Check that because Australia is such a large country national averages wouldn’t reflect regional changes.

Anna Ukkola, of the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of NSW, told Fact Check: “Talking about ‘Australian’ rainfall is just as useful as talking about European or Asian rainfall.”

“The north/north-west of the country has been getting wetter and drives much of the national increase. But parts of the south-west and south-east have been getting drier, in particular in the cool season …”

“In south-western Australia, the last two decades have been the driest since records began in 1900.”

Measuring rainfall

Australia’s rainfall data has been collected and disseminated by the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) since 1900.

The bureau calculates national rainfall averages as well as averages for each of Australia’s eight states and territories, and for specific geographic regions.

These regions include the north and south broadly, as well as the eastern, south-eastern and south-western parts of Australia.

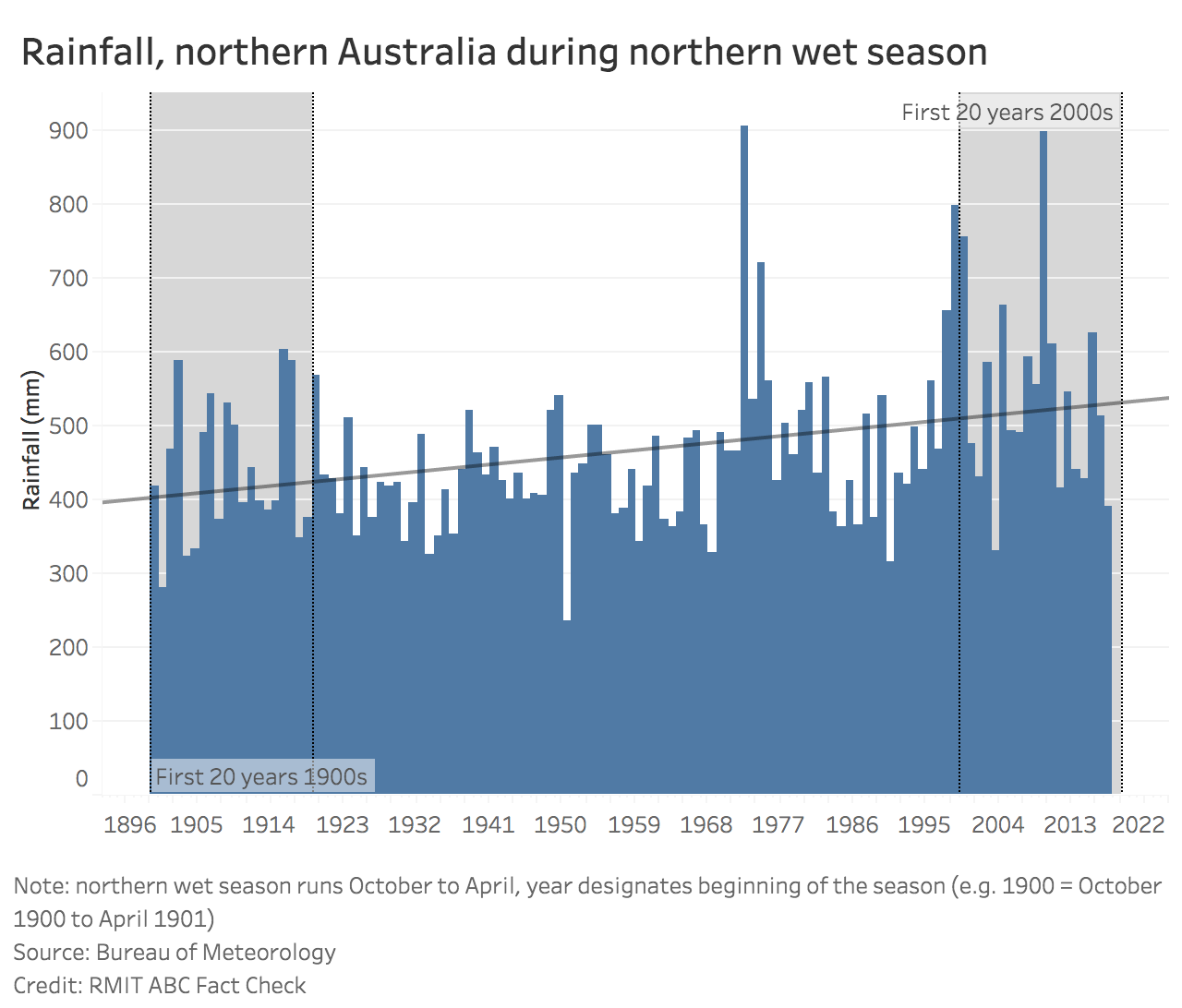

In northern Australia, which takes in the northern half of Western Australia, the Northern Territory and most of Queensland, the wet season (the period in which high rainfall is expected) runs during the warmer months of the year — from October through April.

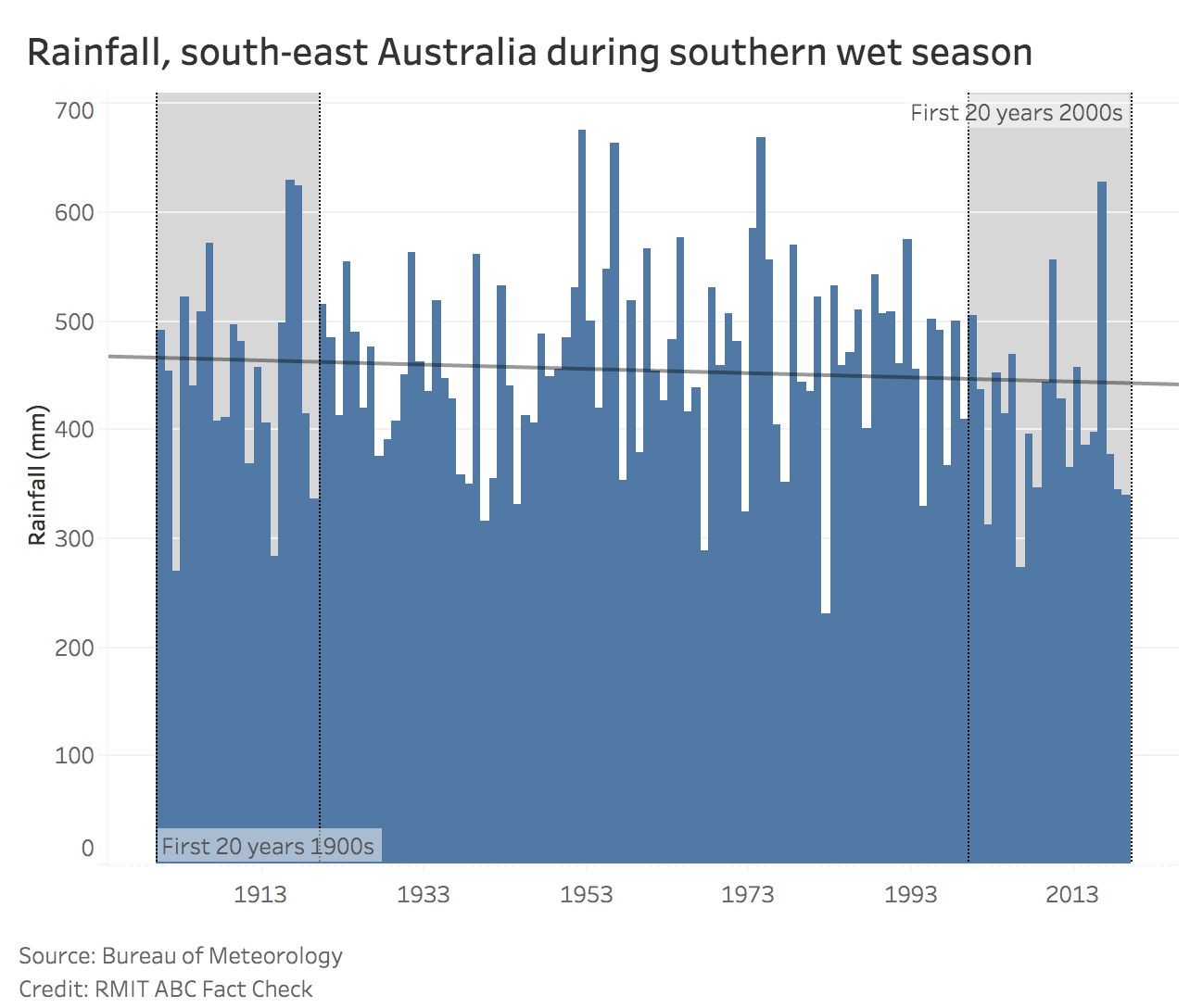

The opposite is so for southern Australia, which includes the southern half of Western Australia and southern Queensland, as well as South Australia, NSW, Victoria and Tasmania, where the wet season occurs in the cooler months of April through to October.

For the sake of consistency, the bureau tracks rainfall changes by calculating variations to the 1961-1990 average, in keeping with international standards.

Considering rainfall patterns for specific regions allows for a clearer view of trends, according to experts.

This is because national rainfall data could be skewed by extreme results in different parts of the country.

University of Melbourne climate scientist Dr Josephine Brown told Fact Check “it is more meaningful to consider trends in different regions and different seasons” when considering rainfall data.

Key influences on Australia’s rainfall

Rainfall across Australia is highly variable, not simply because of the difference in regional wet seasons, but because of different atmospheric and oceanic drivers.

The El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Indian Ocean Dipole both have a major impact on Australia’s rainfall.

According to the Bureau of Meteorology, the former is a natural climate cycle with “a sustained period of warming (El Nino) or cooling (La Nina) in the central and eastern tropical Pacific”.

Among other impacts, the El Nino phenomenon leads to reduced rainfall and warmer temperatures in the eastern and northern regions of Australia.

The opposite occurs with La Nina, which usually develops in autumn or winter and is accompanied by an increase in rainfall in eastern, central and northern Australia, and cooler maximum temperatures in the southern tropics.

Melbourne University’s Dr Brown said El Nino and La Nina occurrences and impacts were important to understand because they are responsible for “a large part of our rainfall variability”.

“It does help to understand the year-to-year variability. And … [during] the 20-year periods that we’re talking about there were a number of major El Nino and La Nina events.”

Another weather influencer is what’s known as the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), which affects a different region of Australia to ENSO, impacting rainfall and temperature patterns over eastern and southern Australia during May to November.

Put simply, “the Indian Ocean Dipole is the difference in ocean temperatures between the west and east tropical Indian Ocean that can shift moisture towards or away from Australia”.

Brown said the El Nino Southern Oscillation was more important for the north and the east of the continent, whereas the IOD affected winter and spring rainfall, in “a band across southern and eastern Australia”.

“They [ENSO and IOD] have a different spatial pattern in how they affect Australian rainfall.”

Rainfall across the country: then and now

Data recorded by the bureau for Australia’s annual average rainfall supports Kelly’s claim.

From 1900 to 1919, Australia’s average annual rainfall was 438mm, which is less than the recorded average (494mm) between 2000 and 2019.

This is despite 2019 being the driest year on record, when just 277.63mm of rain fell — 40% below the 465.2mm baseline average (1961-1990).

This record-low average actually incorporates above-average rainfall in parts of Queensland’s north-west and northern tropics, as well as in parts of Western Australia.

Ben Henley, a lecturer working in Monash University’s School of Earth Atmosphere and Environment, told Fact Check that a national average for one year of data revealed little.

“2019 was a real outlier, an extraordinarily hot, dry year,” he said.

“Extremes can be significant and interesting to look at, but with high inter-annual variability, we could very well have the wettest year on record next year.

“There’s so much variability in Australia’s rainfall. We have to deal with such high variability, and be aware that it can mask underlying trends.”

Indeed, the bureau’s annual climate statement cautions that “every period of rainfall deficiency is different”.

It goes on to say that “the extraordinarily low rainfall experienced [in 2019 is] comparable to that seen in the driest periods in Australia’s recorded history, including the Federation Drought and the Millennium Drought”.

Meanwhile, Australia’s highest national rainfall average occurred in 1974 (759.65mm), followed by 2011 (707.73mm).

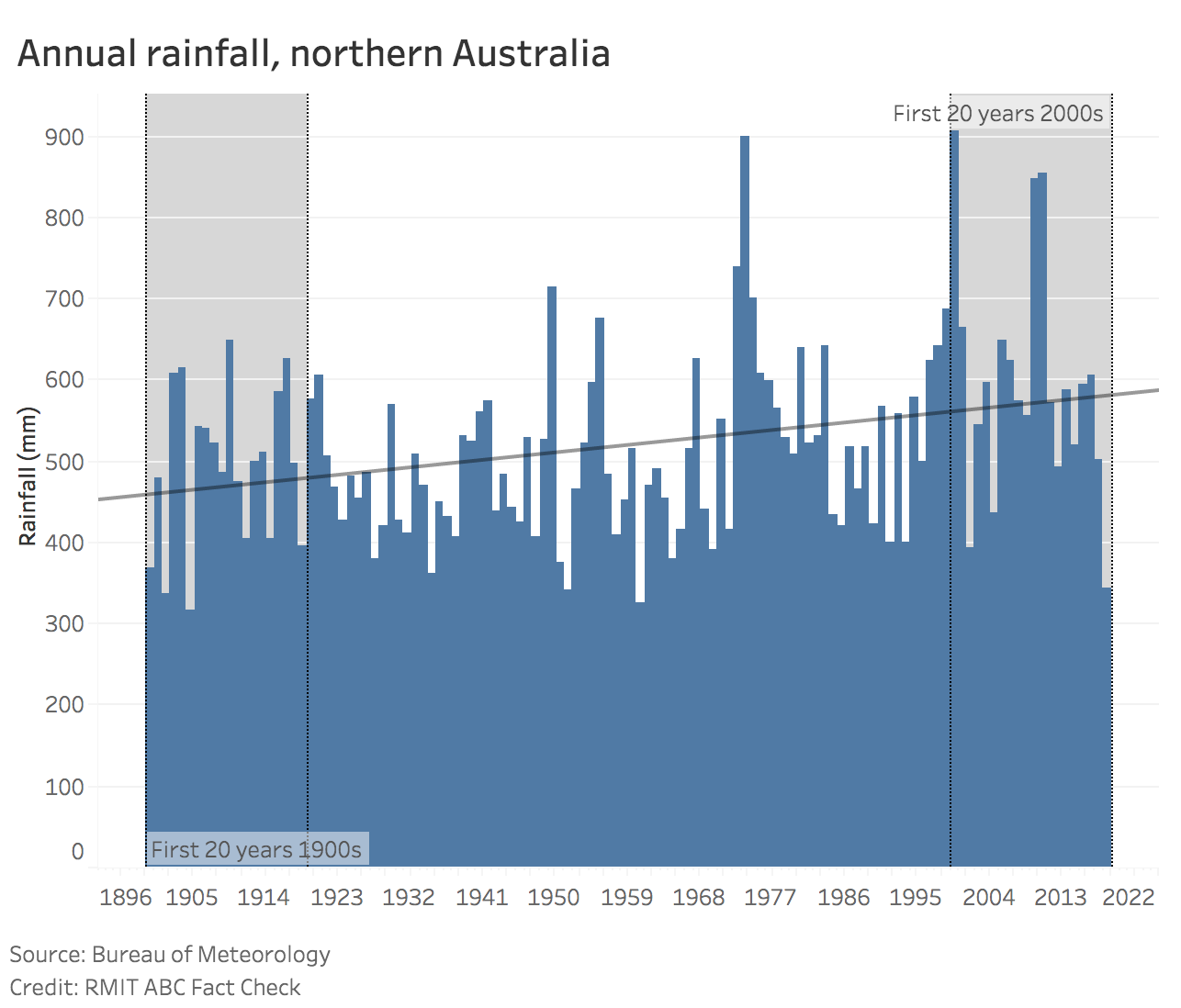

Northern Australia

In 2019, according to the bureau, most of Australia experienced below-average rainfall, with “much of Australia affected by drought“.

However, increased “tropical activity” in “parts of Queensland’s north-west and northern tropics” has skewed the national picture, leading to “above-average” rainfall overall.

Indeed, while annual average rainfall in northern Australia between 1900 and 2019 was 519mm (just below the baseline average of 524mm), increased recent falls during the wet season have been responsible for much of the national rainfall gains.

Southern Australia

In recent decades, rainfall averages across parts of southern Australia have been low.

This has been particularly so during the April to October wet season, which is crucial for agriculture across the region.

While the long-term trend line suggest annual rainfall has been rising in southern Australia between 1900 and 2019, average rainfall during the wet season was 246.07mm — 4% below the 256.1mm baseline average (1961-90).

Brown explained the upward trend in the southern region’s annual rainfall over the 120-year period as influenced by rainfall recordings for inland areas “where there is a weak positive trend”.

The south-west and south-east

The drying trend has been most evident in the south-western and south-eastern corners of Australia where less rain is falling during the cooler months of autumn and winter.

Brown told Fact Check the trend was clear in the decades since the 1970s, while Ukkola said projections suggested the regions would receive less rainfall in the coming years, especially during the cool season which was crucial for streamflow generation and, therefore, water resources.

“In south-western Australia, the last two decades have been the driest since records began in 1900,” Ukkola added.

Dr Henley, of Monash University, said: “We’re seeing significant drying trends in the southern Australian cool season, but in the warmer season, when tropical moisture pushes further south, we have seen some increases in rainfall.”

However, this was largely unhelpful from a water resources point of view, because the higher evaporation in the summer reduces the amount of water flowing into dams.

“A key concern with such a change in the seasonality of rainfall is the amplified effect it has on the inflows into water supply reservoirs.

“If more of the rainfall falls in summer, more of it gets lost to evaporation. Rainfall in the cool season is quite precious in that respect — a lot more of it is converted into runoff.

“So, you can begin to see why seasonal changes in rainfall are really important for water supply and agriculture.

“In southern Australia we are seeing some declining trends in streamflow which is a real concern.

Eastern Australia

Annual rainfall in the east was particularly low in 1902 during the Federation drought, measuring 330.49mm; it was highest in 2010 (1028.39mm).

However, as experts have cautioned, looking at a region’s annual rainfall average isn’t necessarily representative of the broader rainfall trend.

This is particularly so in the east, which takes in the north and the south where rainfall patterns are varied.

Eastern Australia experiences significant year-to-year rainfall variability due in most part to the impact of ENSO. In the eastern half of the country, El Nino events typically produce decreases in rainfall whereas La Nina events mean wetter periods.

What the experts say

Experts contacted by Fact Check said that although Australia’s average annual rainfall had been increasing — with the last two decades among the wettest on record — relying on this measure alone was problematic.

Ukkola told Fact Check: “Talking about ‘Australian’ rainfall is just as useful as talking about European or Asian rainfall.”

“The north/north-west of the country has been getting wetter and drives much of the national increase. But parts of the south-west and south-east have been getting drier, in particular in the cool season…” she said.

Brown said Kelly’s statement did not capture the full story of rainfall and drying trends.

“Australian rainfall is highly variable… so, comparing two 20-year periods may not give reliable information about long-term trends.

“Any average over 20 years is likely to be dominated by the El Nino and La Nina events in that period because they have such a large effect on Australian rainfall.

“They produce very large anomalies — either wet or dry depending on which phase we’re in.

“The other problem is when you’re talking about the average rainfall over the entire area of the continent, it isn’t very meaningful because the trends are different in the north and in the south. Trends and variability in Australian rainfall are different in different regions.”

The north-south divide demonstrated this most starkly.

“Because the total amounts of rainfall are larger in the north, it dominates calculation of average Australian rainfall,” said Brown.

“But, of course, the majority of the population and agriculture is located in the southern part of the continent.”

She added: “The last two decades have seen strongly declining rainfall in south-east and south-west Australia with 17 of the last 20 southern wet seasons below the long-term average.”

Henley said: “On the ground, it doesn’t make too much sense at all to talk about all Australian rainfall.”

“People care about water availability at their specific location, and what’s happening directly upstream.

“It’s important not just to look at total annual rainfall, but also where and when that rainfall falls. We’re seeing changes to what we call the spatio-temporal distribution.

“In other words, where and when rainfall actually falls, which seasons, how heavy the downpour, the duration of time between when rain falls — there’s a lot more to the picture than just total annual rainfall over a very large area.”

Matthew England, of the University of NSW Climate Research Centre, said: “Northern Australia has on average become wetter, and south-east and south-west Australia have become drier.”

Therefore, looking “Australia-wide, total rainfall amounts are useless and irrelevant to the question of recent drying trends over south-east and south-west Australia, because those drying trends are offset by increased rainfall to the north”.

Further, higher rainfall and extreme drought were not necessarily mutually exclusive in a land as vast as Australia, according to Ukkola.

“Higher rainfall can occur with more droughts if rainfall becomes more variable.

“Indeed, Australia’s rainfall has become more variable since the early 20th century and climate models project this trend to continue with climate change.”

Henley added: “We’re acutely interested in understanding when and where the changes in the hydrological system occur and what’s driving them.

“I’m concerned that highlighting particular aspects of the data, without having concern for other aspects, can lead to a broader misunderstanding about the very serious nature of climate change. We have to look at the full picture.

“Climate change is the single biggest challenge ever faced by humanity. We have absolutely no time to lose.”

Principal researcher: Natasha Grivas

factcheck@rmit.edu.au

Sources

- Australia: State of the Environment, Rainfall: Climate, 2016

- Bureau of Meteorology, Indian Ocean Dipole in Australia

- Bureau of Meteorology, El Nino in Australia

- Bureau of Meteorology, La Nina in Australia

- Bureau of Meteorology, Annual rainfall, temperature and sea surface temperature anomalies and ranks, 2019

- Bureau of Meteorology, Annual climate statement 2019, January 9, 2020

- Bureau of Meteorology, Australian Climate Influences: El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

- Bureau of Meteorology, 120 years of Australian rainfall, 2020

- Bureau of Meteorology, About the rainfall timeseries graphs

- Bureau of Meteorology, ENSO Wrap-Up: Current state of the Pacific and Indian oceans, February 18, 2020

- Bureau of Meteorology, Indian Ocean influences on Australian climate

- Bureau of Meteorology, Tracking Australia’s climate through 2019, December 2, 2019

- CSIRO, Climate change in Australia: Projections for Australia’s Natural Resource Management system, 2015

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.