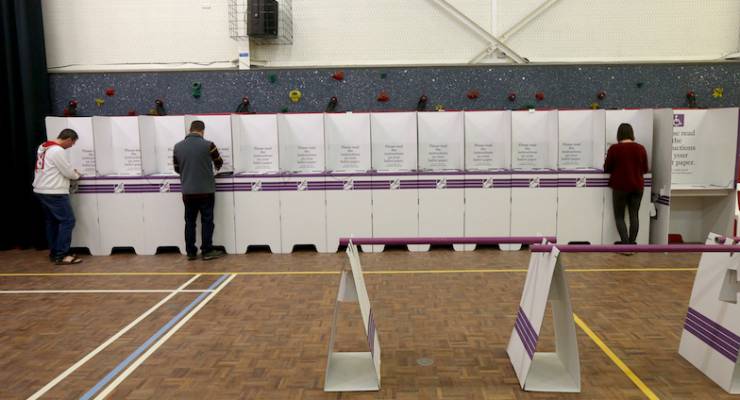

As official warnings and public concern about coronavirus reach an ever higher pitch, more than 3 million Queenslanders will be corralled into polling booths over the next fortnight to vote in compulsory local government and state byelections.

For those unwilling to wear the state’s unusually stiff $130 fine (or the shame of abrogated civic responsibility, if that still counts for anything), the only alternative option is a postal vote — and that window closed with yesterday’s 7pm deadline for applications.

The website of the Electoral Commission of Queensland proved unable to cope with the demand yesterday afternoon, when many prospective applicants were met with error messages upon entering their personal details.

Those experiencing difficulties were advised that they could send their details through by email, although this wasn’t immediately apparent on the application page itself.

The elections are due on Saturday March 28.

According to Graeme Orr, University of Queensland law professor and a noted authority on electoral law, it is still within the power of Local Government Minister Stirling Hinchliffe to postpone the council elections. The byelections for the state seats of Currumbin and Bundamba could also theoretically be called off if the speaker rescinded the writs.

Since a state election will be held in October in any case, it might well be argued that filling the latter vacancies for a few months is not worth the bother.

However, the official position is that neither pre-poll nor election day booths will experience activity amounting to a gathering of more than 500 people, as per the latest advice of the chief medical officer — advice that will surely be showing its age well before next Saturday.

The only concessions in prospect are a possible extension of opening hours at pre-poll booths, and advice that voters should bring along their own pens or pencils.

Certainly it’s a sound principle that established democratic processes are not to be lightly interfered with.

But that hasn’t stopped local elections being delayed for a full year by Boris Johnson’s government in the United Kingdom. It also hasn’t stopped French President Emmanuel Macron from announcing the suspension of municipal elections scheduled for Sunday.

In the United States, Ohio has just called off a presidential primary that was due to be held tomorrow our time (primaries in Arizona, Florida and Illinois will, apparently, proceed), and looming primaries have been delayed until May in Georgia and June in Louisiana.

However, that surely only kicks the problem down the road, as there is no reason to think the situation will improve before then — or even by the time of the presidential election itself on November 3.

Those nervously wondering if Donald Trump might wish to exploit the situation to subvert democracy can rest easy, as any contingency relating to the presidential election would require the consent of the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives as well as the Republican-controlled Senate. It would also have to square with the constitutional requirement that a new presidential term must begin on January 20.

What might happen is that more states will follow the lead of Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Utah and Hawaii in conducting their elections entirely by post — although this method raises genuine concerns about the potential for fraud.

Despite looming elections in the Northern Territory in August, and in Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory in October, there is no sign yet of such measures being contemplated in Australia.

But the emergence of the present crisis raises interesting questions as to how things might go if disaster were to strike shortly before a federal election, where much of the architecture is set in place by an entrenched Constitution.

According to Graeme Orr, the milder end of the scale would involve extending pre-poll voting and relaxing fines for those unwilling to expose themselves to whatever risk.

In the extremity, writs for an election could be rescinded by the governor-general for the House of Representatives and state governors for the Senate, and a temporary all-party government of national unity formed.

But in the absence of a newly elected parliament, such a government would be unable to enact legislation, including the money bills that need to be passed at least once a year to allow government to function.

After giving us Pauline, Clive, Dutton, Canavan, Katter, Joyce (v.1), Bjelke and all the rest, I’m surprised Qlders are still allowed to vote at all.

So the March 28 QLD Council elections could healthily proceed on a BYOP Basis – Bring Your Own Pencil! Beyond satire!

Over the next 11 days, we can expect government/s (They all seem to have a finger in this decentralised pie) to further limit public gatherings, catching up with other international countries.

How the hell do health authorities, who preach isolation as a major effective strategy, allow masses of people to roll through a small number of polling booths on one day?