Australia still has a chance of flattening the curve of coronavirus cases, and we only have 10 days to act.

A draft report by adjunct professor Michael Mike Georgeff, a mathematician and leading Australian expert on artificial intelligence and health technology, shows we need to go hard now, placing 20 million Australians into lockdown by April 7 to keep coronavirus cases under 200,000.

The report’s predictions come from the Susceptible, Infected, Recovered epidemiological model, mapping worldwide trends and responses to Australian cases. Georgeff and his team fed various assumptions into the model, looking at data gathered from China, the US, Italy, and Imperial College London.

“We wanted to find out what was happening because we were not getting enough information from the government,” he told Crikey.

What they found could mean life or death for the country.

If cases climb above 100,000: Australia’s hospitals will be overwhelmed, and the mortality rate will jump from 1% to 10%.

Australia has around 2,500 ICU beds, and 1,500 with ventilators (though this number is increasing). About 4.4% of coronavirus patients require hospitalization, and 30% of these cases require ICU beds for an average of 10 days.

If peak cases stay below 100,000 at any given time, the mortality rate will stay at 1%. As is the case in Italy, if hospitals are swamped the number will jump to ten times that amount.

If we just rely on social distancing: If we keep cafes and restaurants closed and shut schools, the rate of infection would be reduced by 20%, though the timing of the peak wouldn’t change.

If implemented by the first of April, peak cases would climb to just under 4 million.

The model assumes each infected person infects another every 2.6 days; Australia’s growth rate is currently doubling every three days.

If testing and isolation can happen in under two days: Australia’s infectious period is about six and a half days — that is, from the time someone is infected with coronavirus, to the time they self-isolate.

If as soon as someone suspected they may have coronavirus, they were able to get tested, receive results and isolate within two and half days — bringing the average time to four and a half days, counting people who are asymptomatic or don’t get tested — by April first, cases would climb to over two million.

“If we could get tests immediately then you might not need isolation, but that’s not possible,” Georgeff said.

If we tested fast and implemented social distancing: Combining the two above strategies would limit peak infection loads to less than one million.

If we go into lockdown by mid April: If we went into a month-long lockdown from April 19 to May 16, we’d see a reduced peak caseload to around three million people.

Around four million would never be infected and the second wave of the virus, once people are reintroduced into the community, would be smaller than the first.

If we implemented fast testing, social distancing and mid-April lockdown: A combination of all three measures implemented before April 10 would see the peak number of infected people drop to under 700,000, with ten million people not being infected.

Importantly, action after April 10 would add millions to the peak infection load.

If we go hard and fast, now: The report recommends a “hammer and dance” approach: extreme measures now, and then tweaking with re-introduction measures.

“You hit it really hard then play with numbers as you slowly release it back,” Georgeff said. For this to work, people over 70 would need to go into lockdown immediately; 20 million people (most of Australia’s population) would need to be quarantined by the April 7.

In line with other models, 80% of Australians would have to be in lockdown for it to work.

Lockdown wouldn’t last very long either — between one to two months with the appropriate testing measures in place. Case numbers would still be higher than our health system can cope at 200,000 people (reduced by putting more people in quarantine earlier), with four million Australians affected. The death toll would likely be less than 40,000.

Professor Tony Blakley, an epidemiologist at the University of Melbourne told Crikey his modelling had produced similar results.

“Keeping infections beneath 200,000 a day seems plausible. In my very basic model I made it 125,000 minimum,” he said.

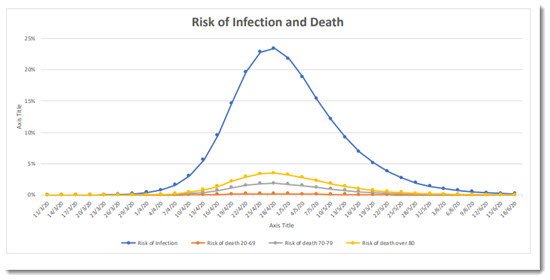

Whatever happens, don’t go out between April 16 to May 13 — this is when the probability of infection is the highest.

Action is needed now, Georgeff says. “It’s all over in a month or two if we act immediately,” he said. “We have to start giving a consistent message to the public.”

This research is consistent with the article “Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance” by Tomas Pueyo

https://medium.com/@tomaspueyo/coronavirus-the-hammer-and-the-dance-be9337092b56

What Thomas’ article also explains is this suppression strategy gives us time – to test & trace a lot more, to properly develop treatments, and in the long run develop a vaccine.

Wash your hands, social distance, stay home. You have one job. Do it well, as well as the medicos who are caring for the ill. Do it now. No excuses.

Common sense would have indicated that a complete shutdown for 3-4 weeks would have been the best option right from the start. But a government focussed entirely on “the economy” over “the people” and still hoping it can spend its budget and have it too, was never going to make the obvious hard choice.

Despite citing “health advisers” for keeping schools open, the reasons given were always economic, not health.

Stimulus 1 was obsolete before it was even declared.

Stimulus 2 is still focussed on economy and not the wider public health implications.

It is not a case of if we have a lockdown, but when, and the health and economic impact will be greater for having waited as longer.

Exactly!

Treat it as a health issue and hit it with everything we have and the economics will be minimised. Everything else is playing around the edges.

“It is not a case of if we have a lockdown, but when, and the health and economic impact will be greater for having waited as longer.”

Funny, that is much the same as can be said for climate change mitigation!

‘Flattening the curve’ is nonsense. All you do stretch out the time it takes for R0 (‘mean infection rate’, or various other definitions used) to play out.

The benefit in ‘flattening’ helps keep the collapse of the health system at bay, which is a significant benefit – but what about the ‘fatigue factor’ over a longer time operating at peak capability?.

Flattening also allows fingers to be crossed, in the hope a vaccine becomes available quicker than likely, and for treatment regimes to be developed.

Juliette O’Brien got close, yesterday, here – https://uat.crikey.com.au/2020/03/25/covid-flatting-the-curve-graph/

As her piece was headed;

“Forget flattening, this is the curve we really need to watch

Simply trying to flatten the ‘hockey stick’ curve of Australia’s exponential coronavirus cases will not help us

stop the virus. To do that, here are the numbers we need to pay attention to.”

Put simply, you need to ‘bend the curve’, not flatten it.

If you can bend the curve, you have taken the R0 under 1. The coronavirus/COVID – 19 has an R0 between 2.0 & 2.5. Flu is around 1.3. Ergo, coronavirus/COVID -19 infects more, faster. Plug in its higher lethality (Mortality Rate), and you have ‘bigger on bigger’.

This medico is not the only one to put this forward, but he is local, so give him a try;

https://www.theage.com.au/national/don-t-flatten-the-curve-bend-it-the-fatal-flaw-in-our-covid-19-strategy-20200324-p54d8f.html

“Don’t flatten the curve, bend it: the fatal flaw in our COVID-19 strategy”

The only 2 countries to bend the curve? China and South Korea;

“This is not what happened in China and South Korea. They reduced R0 below 1, and so dramatically bent their “cumulative incidence” curves away from the exponential line. If you can reduce R0 below 1 and keep it there, the virus quickly dies out. China achieved it through an unprecedented lockdown, South Korea through widespread testing and contact tracing. These measures have produced a shortened epidemic, with fewer people infected and less deaths than would have occurred if they had simply “flattened the curve”.”

The “cumulative cases” graph is easy to find – it’s all over the web.

Those numbers are the cumulative case numbers.

Every man and his dog is coming out with graphs predicting a repeat of Italian tragedy in Australia. This is yet another. These ‘predictions’ are just that, based on other scenarios but still predictions. I predict that what happened in Italy won’t happen here. We have some degree of control, Italy didn’t. Read Linton Besser’s article on ABC website describing what happened in Italy – a clusterfuck from the get go. Stay safe!