To assuage the loneliness of social distancing and remote working, I sent a few “how ya goings” last week to my closest friends, all in our early 20s.

I wasn’t prepared for the bleakness of their responses. Almost all have been stood down without pay indefinitely. Some are unsure how they will pay their rent next month, or if they should refuse. Group chats normally filled with jokes and memes have become group advice/therapy circles for those navigating Centrelink for the first time in their short working lives.

Every young person I know could relay a similar story of economic carnage. Given the greater proportion of young workers in customer-facing or entry-level roles, or on casual, apprentice/trainee or gig-based contracts, we have thus far been the group most impacted by business shutdowns and panicked layoffs.

Recessions hurt almost everyone. Many elderly people, on top of hunkering down in fear of the virus, have watched their super accounts slashed. Many middle-aged people are wondering how to feed their kids without a regular pay cheque.

But amidst the chaos, it is worth reflecting on what the seismic shift wrought by the virus will mean for the next generation, whose working lives will begin amid the greatest economic calamity since the Great Depression.

Last August, The Atlantic writer Annie Lowrey wrote that “the next recession will destroy millennials”. Well, the next recession is here, and the signs indeed look ominous.

Youth out of work

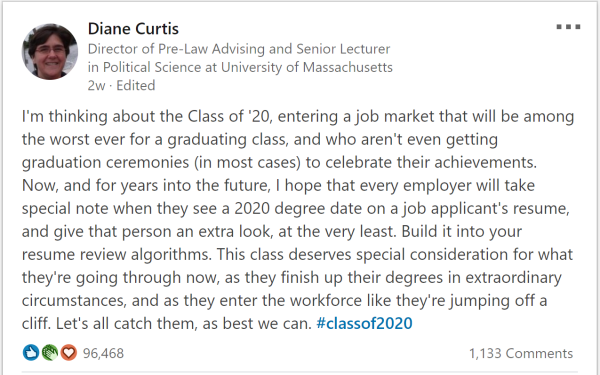

Past recessions have disproportionately impacted young people’s careers. While many people are hurt by recessions, evidence shows that those who graduate from education into a post-recession economy face “significant earnings losses that take years and years to rebound”. It literally stunts your economic growth.

We witnessed this in the “recession we had to have”. Richard Denniss has written eloquently about the raw deal he and other young grads copped in the early 1990s, getting by on crappy casuals gigs and the dole as youth unemployment hit nearly 20%.

We saw this again on a global scale after the global financial crisis (GFC), with long stretches of high youth unemployment, growing waiting times for young people to get jobs in the fields they trained in, and stagnant entry-level wages. Indeed, as the labour market has continued to flounder, myself and many other young people copped the brunt of endemic illegal wage theft.

Now, economist Jeff Borland estimates that two groups of Aussies will be hit hardest in this economic downturn – those losing income due to shutdowns, and those losing income because others have cut back their spending.

“Workers in both at-risk groups are predominantly young”, he says. “More than half are under 35 years of age.”

A rich boomer landlord “recovery”

Not content with prolonging our ascendance up the job ladder, the way authorities typically respond to recessions also tends to delay young people achieving another life milestone — buying a home.

If the economy starts to go pear-shaped, the Reserve Bank drops interest rates. This is necessary, as making credit cheaper coaxes people to keep spending even if clouds are blackening overhead.

So once the chaos blows over, it soon becomes a good time for those with the means to invest (read: older, wealthier people) to do so. But invest in what? Businesses that provide well-paying jobs? Social goods that help the disadvantaged? Nope. In Australia, the government gives investors big incentives to pump far too much money into housing, creating a useless asset bubble.

Now more than ever, as health authorities plead with us to stay at home, we must see the folly of making home ownership immensely harder. We have created a two-tier housing class, with investors hoarding properties they don’t need, while the young and poor remain far too vulnerable to evictions and homelessness at the worst possible time.

A better way

A rich boomer’s investment property will not give my mates a job they can count on. We must not kick off another decade-long sham “recovery” of sluggish wages and booming assets. Only a sustained and fair stimulus, and structural changes that fairly distribute the recovery, will set our economy on a just course after its isolation period.

Before this crisis, I saw little political appetite in Canberra for such an agenda of intergenerational fairness. However, the Morrison government has shown remarkable pragmatism in shaking off its frugal tendencies and becoming “accidental socialists“. Perhaps, just as they saw reason on wage subsidies and raising Newstart, they might come around on investing in jobs for the next generation and curbing our nation’s unhealthy obsession with property.

If not, our nation will give a generation of young people the worst possible start to their working lives. They might even lose faith in capitalism – or indeed, democracy.

We cannot let this virus become a terminal illness for our economy’s future, or the generation it will depend upon.

Welcome to others reality folks. I trust out of this storm we are weathering some empathy will remain when it goes for those whose lands are blighted by warfare and conflict. Whose futures have been wiped out because someone bigger than them decided they would and they could. Whose livelihoods have been put on hold for years just to stay alive. Who cannot shelter at home because it’s either gone, or about to be bombed, shelled or occupied. For those who decided the best option was to flee and seek safety elsewhere. Yes, this is tough, Australia, but it’s a walk in the park on a sunny day for those in Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, Mali, Libya and areas of Myanmar, for example. Remember, Australia will still exist, function and flourish after all this. It’ll bounce, maybe slowly but maybe we’ll, others are completely without hope.

I’d include in the “buggered brigade” anyone under 30 in the EU.

The shit has not yet begun to hit the many fans there, between pollution, socially & racial inequity, sclerotic institutions and by far the largest cohort of useless eaters in comparison to the young.

Britain, in what ever form it survives, and it will, has fewer of the ills of the complacent Continent and far less severe cases of those they do share.

Australia Felix could be the future – except that it’s already been sold out from beneath us.

This is now getting on for 48hrs waiting for approval.

Why does Crikey bother having a comments section – viz making FOUR articles in the Tuesday edition, post facto, closed to comments?

And you expect MONEY for this?

OK, 48hrs gornnn, how about 72?

Everyone has their own story to tell. No one’s asking millennial’s to jump out of a trench and run at a fully functioning, 1909 Maxim machine-gun. If anything, it’s the oldies this time who are at the wrong end of the barrel. ‘One day at a time’, I suppose. And I won’t be retiring anytime soon either…

If anyone, including the young, had not already stopped ‘believing’ in neoliberalism, they have not been paying attention for any of the last 40 years.

It’s a depressing state of affairs when my friends and I who are lucky enough to be in recession proof industries are seeing a silver lining that maybe we could afford a loan for a house.

Though yeah, neoliberalism should be dead but with Josh and Scotty still promising a flattening of the tax rate ‘soon’, it looks like the corpse will remain on life support.

If the stimuli were aimed at building infrastructure, the younger generations would receive some benefit from that.

But as the stimuli have been, realistically speaking, aimed at keeping business afloat and people off the unemployment statistics, once the money has been spent there will be no long term benefit.

The effects of the pandemic will last for many years to come, and many of the businesses being propped up now will fail in the next couple of years.

I can’t see tourism, for example, bouncing back anytime soon.

What a really thoughtful comment. As much as business is doing the right thing at the moment, many are are going to become more efficient after the dust settles. Will they then be hiring or firing??

True Wayne, we are going to have to close our borders for 18 months IF a vaccine is found within 12, or more like 2 to 3 years.