Less than a year after an election fought over franking credits, the Coalition government has dropped more than $200 billion to keep Australians afloat with almost complete support from the opposition.

Political fault lines seem to have been smoothed over, as leaders work together to save Australia from a health and economic crisis. Bills are passed without debate. Union boss Sally McManus and government Industrial Relations Minister Christian Porter are now buds. One of Scott Morrison’s key advisory bodies includes former Labor minister Greg Combet. State premiers of both political colours are happily enjoined with the national cabinet.

But politics never really went away. Beneath the face of bipartisanship, there are plenty of fights going on, from politics to business, sport and the media.

Scott Morrison v the states

One of the first divides to emerge was between Morrison and state premiers. Over a weekend in mid-March, when daily infection numbers were accelerating, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews and NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian, frustrated with the federal government’s pace of action, jumped the gun and leaked plans to shut down all but essential services, leading to a day of communication breakdown and confusion.

And while the federal government has won praise for some of its decisive, well-supported measures to combat the crisis, it only arrived at many of its policy positions after much pressure. Morrison initially appeared reluctant to shut things down aggressively. The government spent much of the week before it introduced the JobKeeper payment arguing against the need for such a wage guarantee. The government only extended the coronavirus supplement to Youth Allowance and Austudy after pressure from Labor and the Greens.

And there remains the tricky issue of state schools. As students return to school in Victoria, the prime minister insists that schools stay open. But the state government still wants students to stay home unless they cannot learn remotely, with Andrews saying keeping kids away from schools was “common sense.”

The Ruby Princess

The decision to let the Ruby Princess dock is a stain on Australia’s otherwise broadly competent management of the pandemic.

So far, 18 deaths, and 700 cases, about 10% of our total number, are linked back to the cruise ship. Since that outbreak, the blame game has shifted back and forth between Australian Border Force (ABF) and NSW Health. Within days of the ship docking, NSW Health Minister Brad Hazzard admitted letting off passengers was a mistake. Meanwhile, Berejiklian told cabinet it was ABF’s fault. The next day, ABF boss Michael Outram said it was NSW Health’s fault. NSW Police have commenced a criminal probe into the debacle, set to last till September.

Are we there yet?

As Australia’s infection curve trends down, and it becomes clear that we have so far escaped the apocalyptic scenes of Europe and the US, pressure for the economy to reopen is intensifying.

Opinion pieces in The Australian Financial Review, The Australian, and The Sydney Morning Herald, among others, have pushed to open things sooner for the sake of the economy. The call to relax restrictions as soon as possible has also gotten traction from several business leaders. Governments and health officials are less hasty. Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt says restrictions can’t be relaxed until we’ve seen a sustained decrease in cases, an increase in rapid response capabilities, and a clear exit plan. And scientists note that experiences in countries like Singapore show that if we take our foot off the gas too early, the numbers can shoot back up. Still, expect this debate to intensify over the coming weeks.

How do you solve a problem like the NRL?

The future of the NRL has somehow become one of the most intriguing COVID-19 suplots. The league was one of the last sporting competitions in the world to suspend its season on March 23, just 24 hours after pledging to keep playing. Chair Peter V’landys had already gone begging for public cash. Then there was the brief, absurd pipe dream of an “NRL Island” — keeping the game afloat by isolating it on a tropical island off the coast of Queensland.

Last week, the league announced plans to resume the season by May 28. V’landys said he had confirmation from NSW Police that it was safe. But state and federal health officials said they hadn’t spoken to him for months. Amid all that came a public feud between the league and broadcast partner Nine, whose spokesperson last week accused the body of mismanaging the game for many years.

The fight for our civil liberties

In our haste to eradicate the spread of COVID-19, we could be sacrificing our civil liberties. States have given police broad powers to issue steep fines and possible jail time to people for leaving their houses, and there are already concerns about their overuse.

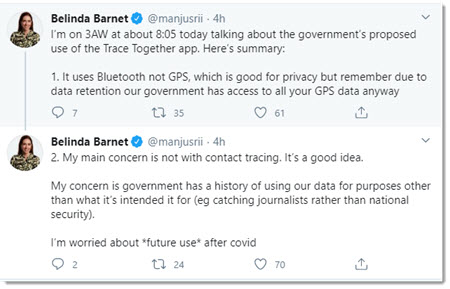

In a few weeks, the government will unveil an opt-in app that uses phone tracking to trace the spread of COVID-19. While contact tracing is crucial to the fight against the virus, the app will give governments an extra tool in its surveillance arsenal. While it can already track our location, the app allows Bluetooth to determine who we’ve been close to, raising fears that its use will become normalised well after the virus recedes.

Just a point of geography. The media reported that the NRL was going to use a camp at Calliope in Qld to play their games. Calliope is not an island – it is a town west (inland) of Gladstone in the Capricornia region of Qld. Silly I know, but it really annoys me when southern media experts show their ignorance about the geography of this large state.

I wouldn’t trust our Government with a tracking app for a second. They have never shown even the slightest bit of digital responsibility, and I can’t imagine it starting now. As with a lot of what’s happened, it’s all chickens coming home to roost for a government who has spent the best part of the decade reducing trust in the government as part of their overall governance strategy.

Also on schools, I honestly believe the only reason Scotty is out calling for everyone to go back is that he is genuinely too stubborn to admit he was wrong weeks ago.

So glad that I only have a $10 dumb phone.

To my mind bipartisanship is not possible in a democracy.

If all the parties act together surely that then makes them a single party. Single party states are not then democratic, as there is no one else to vote for.

Am I wrong?

The USSR reportedly had a vestige of democracy in its one-party system. When you picked up your ballot paper you could vote “Yes” or “No” for your single candidate. If your candidate was defeated, as sometimes happened, the Party had to find a better candidate. I’ve heard that Russia preserves this system with multi party elections. I was told you can vote “None of the above” to reject all the candidates and force a rerun with all new candidates. If we had that system here I suspect we’d have a lot of reruns until the parties started to understand it.

THE SADDEST of the events has been the appalling handling of the Ruby by the unequivocally responsible Border Force– it is beyond belief that Dutton has not resigned over this, and until he does the deaths will be floated around as a political curse until they land where they may as the leader of the Border control at national level cannot be found…

Not as serious, but equally appalling is the treatment of the Biloa family…. what a coincidence? by exactly the same shrinking violet from his clear responsbility–Dutton.

Albanese went into deep hibernation when Labor lost. He refutes all of Labor’s good pre-election policies, I believe the ALP is told to keep quiet and I do not believe he stands for any Labor principles.

Probably more useless than Joe Biden v Trump.

Albo also writes in News Corpse – Shorten refused to meet Murdoch.

Without a decent opposition, Morrison swans off with the next election.

very depressing as Dutton gets away with murder. Taylor secretly destroys the environment further.