Is the current generation of conspiracy theorists any different to those of yesteryear?

Are the virus hoaxers, who think COVID-19 is a Bill Gates plot, or anti-vaxxers, with whom they’re linked, or QAnon adherents, or “replacement theory” white supremacists, or incels, any different to previous generations of anti-Semites (who still blight society, of course) or anti-Communists convinced that Moscow controlled the world, or anti-Catholics who saw all Catholics as agents of the Vatican, or anti-Masons… on and on the list goes.

There have always been conspiracy theorists, a minority of the population who are characterised by, in the words of Norman Cohn, “the megalomaniac view of oneself as the Elect, wholly good, abominably persecuted, yet assured of ultimate triumph; the attribution of gigantic and demonic powers to the adversary; the refusal to accept the ineluctable limitations and imperfections of human existence…”

Richard Hofstadter, in his seminal essay on “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”, argued that

Certain religious traditions, certain social structures and national inheritances, certain historical catastrophes or frustrations may be conducive to the release of such psychic energies, and to situations in which they can more readily be built into mass movements or political parties … Perhaps the central situation conducive to the diffusion of the paranoid tendency is a confrontation of opposed interests which are (or are felt to be) totally irreconcilable, and thus by nature not susceptible to the normal political processes of bargain and compromise. The situation becomes worse when the representatives of a particular social interest — perhaps because of the very unrealistic and unrealizable nature of its demands — are shut out of the political process.

From the perspective of 2020, Hofstadter’s United States of 1964 looks positively benign, and its predominant conspiracy theory — that communists had seized control of the US government, the media and major cultural institutions — seems fairly tame.

But the idea of a society that is highly polarised, unable to compromise with itself, and where significant groups feel themselves shut out of power, feels very familiar, particularly after three decades of neoliberal policymaking that really has shifted the rationale of government to looking after powerful interests rather than the public interest.

What is very different is the internet. There’s long been a broad tendency to blame every social ill on the internet, in the same way that video games, rap, television, rock’n’roll, radio etc were blamed for previous ills.

The internet is technology, entirely neutral in its operation, but likely to amplify existing social characteristics because it facilitates connection and communication. That’s a boon especially for minority groups who can connect with each other on a global basis whereas, in analog times, their connections were limited by geography, family and workplace, or by the analog methods of information distribution.

So the conspiracy theorists of 1964, with their obsession with communists, their hatred of civil rights and their fear of fluoridation, had far less capacity to connect with each other and encourage and influence each other than modern conspiracy theorists, who exist almost entirely online.

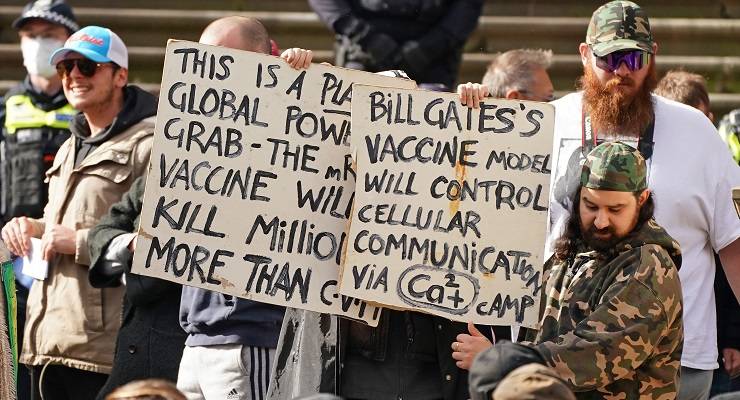

This is why a protester at an anti-lockdown rally in Melbourne will hold up a sign devoted exclusively to QAnon and other US and Trump-affiliated conspiracy theories.

Australian conspiracy theorists no longer bother with Australian-made conspiracies — they use fully imported ones, almost always bearing a proud Made In the USA label. Angry opponents of globalisation and fierce patriots, they’ve gleefully embraced the homogenisation and free trade of conspiracy theory that has turned them into protesters indistinguishable from one another in Dallas, Melbourne, London.

But the internet doesn’t just connect ely connects them up, it reinforces them. Unlike analog-era conspiracy theorists, modern day ones can spend their entire lives in a conspiracy bubble, never needing to stir forth into the real world.

They can filter their media feeds to delete any evidence that contradicts the conspiracy, and highlight interpretations of events, however absurd and contradictory, that reinforce it. They can egg each other on, and have their beliefs normalised; the conspiracy theorist in the 1960s was constantly at risk of reading something or talking to someone who might convey how far outside normal life their belief system was.

Now, you can have your irrational beliefs constantly affirmed, to the point where you become convinced that not merely are you the rational one, but that people who refuse to believe the conspiracy are maliciously irrational. The internet normalises abnormality of all kinds, good and bad.

That may well be a reason why so many conspiracy theorists are now considered actively dangerous. White supremacists, “sovereign citizens” and “Great Replacement” advocates have long been identified by US law enforcement agencies as the major domestic terrorist threat in the US. More recently, incels have been identified as an emerging threat after a number of mass murders carried out by misogynist young men who view feminism as a plot against their right to have sex.

And in 2019 the FBI identified “conspiracy theory-driven domestic extremists” as a threat, who likely “will emerge, spread, and evolve in the modern information marketplace, occasionally driving both groups and individual extremists to carry out criminal or violent acts”. Its report specifically mentioned QAnon theorists.

Just because US security agencies identify someone as a terror threat doesn’t make them one — the likes of the FBI and the NSA have a history of identifying peaceful protest groups as potential threats, including Dominican nuns and Greenpeace. But when QAnon members plead guilty to terrorism charges and fire guns in a pizza restaurant crowded with families, there’s a solid base for law enforcement agencies to worry about them. Anti-vaxxers, too, have increasingly shifted from online to real-world harassment.

The issue in Australia is whether ASIO and the AFP — who were taken by surprise by the Christchurch massacre, having believed that far-right extremists were incapable of mass-casualty attacks — are as up to speed on the emerging threat from internet-fueled conspiracy theorists as their US counterparts.

Christchurch prompted ASIO to be a lot clearer about the terrorist threat from the right — to the fury of Peter Dutton, who lied that left-wing terrorism was an equal threat. But the pandemic, and the irrational claims of virus denialists, might serve to focus their minds away from the threat posed by journalists and whistleblowers and toward internet obsessives who not merely peddle conspiracy theories, but are prepared to hurt and kill for them.

In my long experience wacky conspiracy theorists are a lot less insulated from the ridicule and opposition of the real world than is often made out.

I have an old friend who’s been famous for decades for latching on to every nutty conspiracy going. And for all those years he’s had all his mates and more recently his adult children, challenge, ridicule and dismiss each and every one of them. He is however on every other level a sociable person who works hard and loves his family.

It’s never been a surprise to me that the worst crimes of such types are the socially isolated lone wolves. They don’t get that feedback from the everyday world to balance the nonsense they feed each other. The best thing normal people can do is to squarely challenge and ridicule these loons whenever the situation presents.

I was shocked to find my sister and niece the other day thought that the doco “Plandemic” made a lot of sense! And these are my own blood relations living in Sydney, not some whack jobs living in hillbilly USA. For the first time it scarily brought home to me the power and reach of crazy conspiracy theories. I tried to non-confrontationally talk about “alternative, science-backed” perspectives, but they weren’t having a bar of it. The encounter actually made me feel nauseous.

Yes, their passion is scary.

I wonder how much conspiracy theories are actually multiplying, or just being amplified with the new media. Racism is a good example where racists are getting more vocal, despite a number of measures showing society is less racists. The racists are emboldened because they’ve now got their own echo chamber, yet they are increasingly a fringe group. Taking the conspiracies as mainstream instead of a vocal fringe could very well become self-fulfilling.

Whether it’s just a few loud voices, or a growing chorus of angry paranoid people with a tenuous grip on reality, let’s hope the security organisations in Western countries take them as a serious threat to public safety.

I received in the mail this morning a pseudo newspaper amongst a lot of other junk mail which recently has been delivered by Australia Post . I didn’t bother reading the pseudo newspaper because a quick scan revealed that it contained a heap of articles that can only be described as demented “bullshit”. If indeed this crazy “newspaper”was in fact delivered by AP then that organisation stands condemned and is aiding and abetting the embedment of right wing fascism in this country. I refuse to name the title of this so called newspaper as to do so would give it some semblance of legitimacy.

There’s a piece on ASPI today that shows how closely aligned the motivation and ideation of the NZ mosque shooter and many Islamist terrorists are, based on their manifestos.

Also: 5G cellphone towers are being burned in the USA now, (not just England and Europe any more).

Most of the world _is_ too complicated to understand. A large part of human brains is now thought to be dedicated to inferring motivation in those around us, a useful adaptation for a social species. There’s a down-side though, in that it predisposes many people to look for (and find) motives for things that “just happen”. If there aren’t any people obviously involved, then secretive cabals must be responsible…

On the other hand: it could also pay to keep an eye on who might benefit from impairing the deployment of 5G.

“A large part of human brains is now thought to be dedicated to inferring motivation in those around”

It was ever thus, Andrew. We haven’t evolved one iota from caveman.