Social media has exposed what many people of colour have known for years: the police force has a racism problem, with some officers far too keen to issue a beating.

Twitter, Facebook and Instagram have become platforms for seeking justice for what’s unjust but obscured from public view. Through social media we’ve also learnt just how many officers are complicit in the brutality of their peers.

These images and videos have converted the powerlessness often felt by people of colour into action. Rather than hearsay, bystanders can now contribute evidence by live streaming police violence and showing us what police would rather be kept hidden.

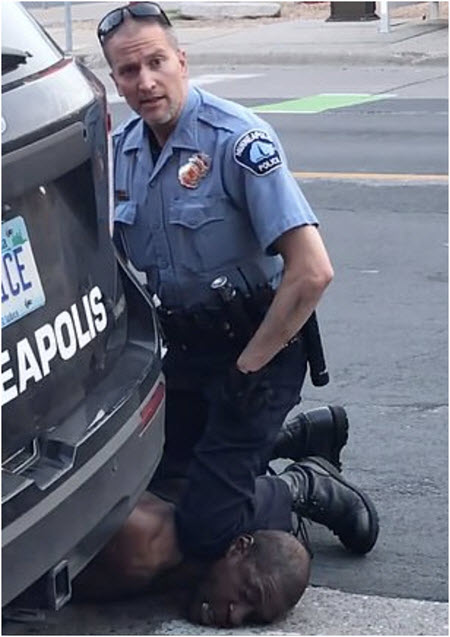

The viral eight-minute video of a police officer kneeling on the neck of George Floyd, killing him as he said, “I can’t breathe”, has sparked three weeks of protests.

The sense of order and authority the police have come to represent was dismantled by justifiably angry protesters who lit buildings on fire, looted stores and destroyed colonist statues.

Much like the bystanders who told police, “he’s not moving” and they should check his pulse, we felt a deep sense of powerlessness witnessing Floyd’s death through our screens.

But without that video and the protests that followed, ex-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin and the other officers could have very well gotten away with their involvement in the killing.

Floyd’s death was sadly reminiscent of the police killing of Eric Garner in 2014. Footage filmed by a bystander showed the 43-year-old father being wrestled to the ground in a chokehold by a police officer before turning limp. Like Floyd, he said, “I can’t breathe”.

After a grand jury failed to indict the officer, protests erupted in New York, again thanks to the power of the image — and social media.

The brutal bashing of Rodney King in 1991 might have been the first viral video of police brutality. In the video, more than 20 officers responded to alleged speeding. Ten of those officers stood around and watched King get beaten with batons and kicked on the ground. What followed was riots across Los Angeles.

Australia isn’t immune to systemic racism in the police force — you just have to look at the fact there have been 437 Indigenous deaths in custody since 1991 and not a single conviction.

Footage of a police officer kicking an Aboriginal teenager’s legs out from under him, making him fall face first, caused outrage as thousands marched in the country’s Black Lives Matter protests over the long weekend.

And forever seared into the Australian memory are those images of Dylan Voller in Don Dale Detention Centre strapped to a chair, with a bag over his head. They sparked global outrage and prompted a royal commission.

Social media is a crucial tool to expose injustice but these images also prompt the question: what goes on when the cameras aren’t rolling?

Again, the issue is NOT this 437 number. IT is not proof of racism, although the number of indigenous people in custody is.

Even the Guardian admits:

“Then, as now, non-Indigenous people died in greater numbers, and at a greater rate, in custody than Indigenous people.”

So why are the majority of aboriginal deaths in custody from natural causes?

Should every time that someone dies of natural causes should we be picking a random police or prison officer and charging them with causing “death by natural causes”?

The 413 deaths is a good statistic for media sound bites arguing police and prison officers have murdered every single one, but no one likes to highlight things like, a huge number of these deaths are natural causes, a few are suicides, some are from say pursuits where police never touched them and they died in subsequent car accidents. If you take into consideration all the deaths that in no way could be argued are murder all of the sudden the number of Aboriginals arguably “murdered” by police or prison officers becomes a whole lot lower.

Maybe someone should spend some time going over the Australian Institute of Criminology report into deaths in custody since 1991 and actually drill down into what the 413 deaths in custody actually means.

An addendum to the last comment is that I see merit in looking at aboriginal deaths in custody and trying to avoid them where possible. I just don’t like people going out and insinuating there have been 413 murders since 1991.