The GST commenced 20 years ago today, and within neoliberal circles there’s plenty of commemoration. The GST is — to use the lie of Peter Costello — the “last great reform”, the last time when politicians were bold reformers, in dire contrast to the wishy-washy current generation.

It’s no mere exercise in nostalgia, of course, but the basis for a demand that further reform be undertaken, including of the GST — a demand made all the more urgent by the pandemic.

Rather than being the last great reform, there is no evidence the GST has produced any of the benefits claimed for it at the time by the Howard government and its media cheerleaders.

Let’s go through them.

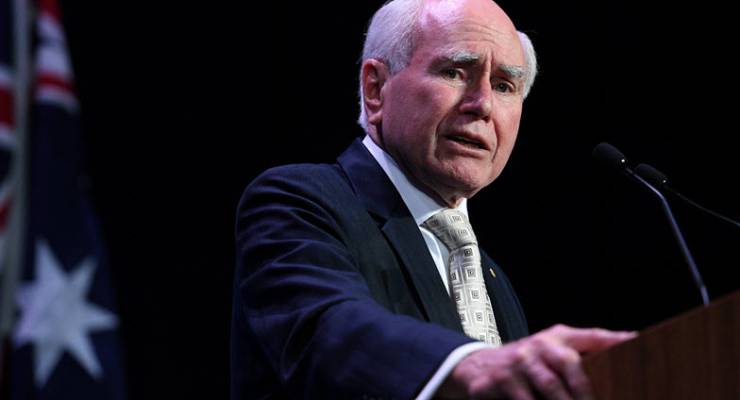

The GST was supposed to end the black economy. “The cash or the black economy runs rampant. The introduction of a goods and services tax will drag the cheats into the net,” boasted John Howard in 1998.

The current government’s own Black Economy Taskforce, however, estimated it was still worth up to 3% of GDP in 2017, or $500 billion to $600 billion — so large that the government has introduced a $10,000 cash limit to try, again, to stop it. The GST didn’t kill the black economy; rather, as tax expert and (briefly) Labor MP David Bradbury once noted, it merely formalised it at 10%.

Indeed, the government was warned at the time it was engaging in fantasy with its claims about the black economy.

As a consumption tax, the GST was also supposed to lift the national savings rate, in line with economic theory.

That’s still an argument trotted out by more recent proponents of consumption taxes. Australians were routinely scolded in the 1980s and 1990s about not saving enough (and relying too much on foreign debt, with the Coalition warning that there was x-thousands of dollars of debt for “every man woman and child in Australia”). After the election of the Howard government, the household savings rate fell from 5-6% to less than 2% — it even went negative in one quarter.

But after the introduction of the GST, the household saving rate actually fell even further, with eight successive quarters of negative savings between 2002 and 2004. The only thing that boosted household savings was the financial crisis — between late 2007 and late 2008, the household savings ratio went from 1.6% to 10%, and didn’t fall below 7% until 2015.

The GST was also supposed to, in Howard’s words, “guarantee growing levels of revenue flows to all of the states. And what that means is that the states will be able to find a secure funding base to provide the schools, the police services, the hospitals, the roads, and all of the other day-to-day services that all Australians wherever they live have a right to expect.”

In fact, the states rapidly fell to complaining about the formula used to allocate the GST. While that’s not a problem about the GST, it has become clear in recent years, as consumer spending has shifted toward food and health services, that the exemptions baked in by the Howard government have crippled the capacity of the GST to fund “schools, police, hospitals”.

The wounding impact on retail trade of the government’s policy of wage stagnation has also hurt revenue. Once-impressive annual GST revenue growth of 9% in the 2000s has now reduced to just 3.6% in the most recent budget papers. And where revenue once routinely exceeded budget forecasts, for the year just ended, even before COVID, the government was expecting GST revenue to come in $6 billion below its initial budget forecasts several years ago.

The GST was also supposed to be more efficient than the taxes it replaced, with sundry state and federal “nuisance taxes” (which did not need a GST for them to be removed) and previous wholesale sales taxes. “A goods and services tax will sweep away the 10 inefficient commonwealth and states taxes we now have,” Howard claimed, which would, he predicted, “enable us to reach our dream, our goal, of becoming a major financial centre in the Asia-Pacific region”.

The GST in fact hasn’t stopped Sydney — our only viable candidate for a major financial centre in the Asia-Pacific — slowly falling behind other major Asia-Pacific financial centres since then. But more problematically, there is no evidence of any of the efficiency benefits claimed for the GST — because no one has bothered to try to identify them.

The efficiency gains from a GST were simply asserted by the Coalition, by economists and by the media, but no one has ever sought to verify whether such “dynamic benefits” were achieved, especially given the distorted implementation of the GST via the Senate, or whether they were simply plugged into the modelling used to justify the GST without any attempt to verify that they existed.

Those benefits may have been realised, but without evidence of them, they have all the substance of the promised elimination of the black economy and rise in household savings we were told we were about to enjoy 20 years ago.

Tomorrow: what evidence — if any — is there of the GST’s success?

Do you think the GST has benefited Australia? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication in Crikey’s Your Say section.

Well what a surprise, another neoliberal myth shown to be false. Watched all the same under Thatcher with VAT replacing sales tax etc. Just the same outcome there too.

I dislike the GST because it’s a regressive tax. The poor pay a higher percentage of their income than the rich.

It should be replaced with a progressive wealth tax. An average 1% annual tax on net wealth would generate around $120 billion a year, and replace many other taxes such as the GST and capital gains tax.

And with modern information technology, it would be easy to administer, and impossible to avoid.

The rate on the poor could be set much lower than 1%, so they’d pay very little. And the rate on the rich wouldn’t be much more than 1%.

I agree, and fines should be on the same principle. The $1500 or so fine for lockdown breaches in Victoria must be catastrophic for some.

Does anyone know what the payment rate is? Are people paying?

Does anyone know what the payment rate is? Are people paying?

I too agree. Despite the cavils dumber economists have with Piketty, his proposal for taxing wealth annually (not only at death) make a lot of logical sense

How exactly does the poor pay a larger percentage of their income given it is a flat rate of 10% and largely non descretionary items such as food is GST free.

I think the GST has largely done its purpose as designed at the time. I remember being excited at coca-cola would reduce in price as it hit with a 25% sales tax.

I think Bernard is being a bit too harsh, the old sales tax returns used to take us about a week each month to get done, the GST BAS returns cut that time down to an hour or so a month. It is a shame that like most things the LNP do, they stuffed the GST by giving exemptions for things they and their mates spend most of their money on rather than looking at what would have been best for the country.

Yes. But you still have to spend your time being a tax collector.

Thanks for the much needed scepticism about the GST, Bernard. The so-called “efficiency” of the GST is a purely ideological claim. In the neo-classical model of general market equilibrium, it is efficient because the model supposes that markets are complete (for every good there is a market), every market is perfectly competitive, and wages are competitive wages under full employment. Unfortunately, none of those assumptions is correct in the real world. The burden of taxation is shared equally between goods and does not cause shifts in demand in itself in the model economy but what might be needed in the real world is that the burden of taxation fall more heavily on consumers of cigarettes, consumers of oil and on products whose price is held high because, for example, despite gaining profits from being able to run its factories year round, the US firm Weber, wishes to extract more profit from its Australian customers for barbecues by charging them much more than the US price translated into AU dollars, with delivery costs added. In a world with large externalities and weakly competitive markets, a GST cannot be efficient in the way it is in the ideal model economy of neo-classical economics. The advantage of the GST is to investors, who get a regressive tax on consumers and tax relief for removal of other tax costs on their investments, which are not taxed by the GST because making yourself healthy does not count as consumption to be taxed by a GST. In real economic terms, it will have no effect whatever on coming out of recession but, hey, if we need to raise taxes for public works, why not raise our most regressive taxes. No doubt we can count its cost in cups of coffee.

“wealthy” instead of “healthy”. This wasn’t a typo, since “w” and “h”. It was the all too helpful automatic spell checker, which makes the wrong guess too many times.

since “w” and “h” are too far apart on the keyboard.

“it has become clear in recent years, as consumer spending has shifted toward food and health services, that the exemptions baked in by the Howard government have crippled the capacity of the GST to fund “schools, police, hospitals”.

At the risk of causing myself to vomit by defending Howard, it has to be said that the only reason the food exemptions are in the current version of GST is that Meg and the Democrats refused to pass the legislation in the Senate if they weren’t. Howard and Costello wanted the purer “no-exemptions” GST that Roger Douglas created in NZ.

The only reason we have the GST at all is also because of “Meg and the Democrats”.

Which is why they no longer exist.

Fred could not be more wrong and similarly for Jane. The demise of the Democrats is an interesting sociological phenomenon and had nothing to do with the GST. The Federal Greens are in not a dissimilar predicament.

See my embargoed note to this topic tomorrow (maybe).

Exactly B Jane. I will never forget the smile of Meg Lees alongside Peter Reith, having negotiated the introduction of the massive GST that hurt poor people the most.

On such a massive tax, she was so proud to have got the LNP to exclude books and some such, and so imposed a burden on many on low incomes.

Meg Lees disappeared in to political obscurity, ratting on her own party’s policy to oppose the GST in the 1998 election. After that, The Democrats became political history, fast.

Always found it strange that the media legend persists that Howard got a mandate to introduce the GST. Opposing it were 4 parties- the Oz Democrats, ALP, One Nation and The Greens.

The 1998 primary vote of those 4 parties opposing the GST introduction was close to 60%.

If 60% of voters don’t vote for a Party, and they achieve Government, does that mean they can make an unchallenged claim they have a mandate for all policies?