Someday I will tell you about my past involvements in both sides, Sir John Kerr writes of left and right politics in one of his absurd, toe-curling letters to a Buckingham Palace private secretary who could not care less.

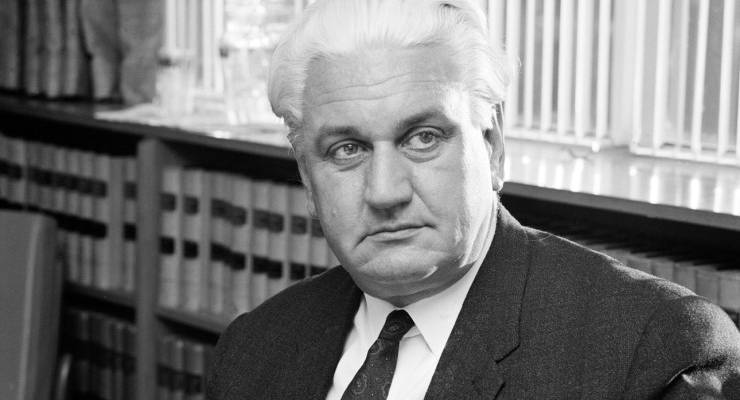

It was a strange place for a strange man to wind up. From the start, he had been seen by his friends as a man who might do great things. John Robert Kerr had been born in Balmain, his father a worker and radical unionist at the Eveleigh railways works (now a failed arts venue — symbolism will never be far away in this story).

He gained a scholarship to Fort Street High, the Sydney selective high school, and then another one to Sydney University in 1932, having topped the year. There he impressed everyone with his intellect, his drive, his force of character. He was the man who had read everything, particularly in sociology and history; Marx, Lenin, Nietzsche, Spengler, Sorel, Hegel, Pareto, the works.

He would later be famous for finding a mentor in Doc Evatt, dashing High Court judge and author of a study of the governor-general’s “royal prerogative” powers. But another Fortian had already helped him along the way: Alf Conlon, a young freebooting Sydney character who had spoken at his old school as part of an outreach project for his employer, the Shell Oil company. Conlon persuaded Kerr to set his sights on university. Indeed he joined him there, as a mature age (24-year-old) medical student.

Kerr was of the radical left, because who among the working class contingent of Sydney Uni would not be in the 1930s, and though he never joined the Communist Party he was part of a louche group of fellow travellers who would form the nucleus of a Sydney set.

Kerr would know many of the radicals who would dominate left politics for two generations — indeed, he would introduce several of them to the works of Marx. They were bohemian, anti-imperialist, anti-fascist, certain that world war was coming, and modern in their habits. Someone remembered Kerr, stirring soup, with a child on his hip, and reading Schopenhauer at the same time.

He was muscular, handsome and rock-jawed, a socialist-realist portrait of himself.

By the late 1930s, much of that group, though still Marxist, had rejected Stalinism and gathered around the dynamic organiser Nick Origlass — a mainstay of Sydney radicalism for half a century in a movement that was not yet known as Trotskyism. It was the start of a path that many others have taken.

When the war came, Kerr’s mentors came good. He was taken up into the unit that Conlon — starting from a base as Sydney Uni SRC president — would form called The Directorate of Research and Civil Affairs (or the Directorate for short), whose brief was half unconventional warfare, and half spying on the Americans for Australian general Thomas Blamey.

Based in Victoria Barracks on St Kilda Rd, the Directorate comprised poets, anthropologists, anarchists, with a floating brief that soon evolved into a focus on the Pacific and Australia’s role there. By 1944 Kerr was de facto deputy to the brilliant, shambolic Conlon, as the Directorate became responsible for the “Ern Malley” hoax; negotiations with the CIA-precursor OSS about taking over parts of Britain’s Asian empire; for US geological survey flights over the Australian desert; and for the plan to create a national university in Canberra from which to build an Australian sphere of influence and an Australian atomic bomb.

By the end of the war, the Directorate was running Borneo. Yet this was not the high point of Kerr’s war, which came when Evatt took him as senior staff to the inaugural UN conference in San Francisco and became acting secretary-general (by alphabet — Argentina was excluded for fascist sympathies), quite possibly saving the thing, with Kerr his rock-solid organiser.

It would never get as good again.

How could it? Back home, as the peace turned into the Cold War, the great clash of world politics became as sleazy and cynical as it had in 1939. Kerr and others shucked their last parts of left radicalism when the Communist Party stole the election of the steelworkers union leadership, back in the Balmain docks which Kerr was born within sight of.

A court challenge by worker Laurie Street with Kerr as his barrister occurred as Robert Menzies tried to ban the Communist Party. Street was a Trotskyist. He soon ceased to be one, as his cause was taken up by US agencies who organised for him to tour the US, warning of Communist infiltration of unions.

By now Kerr had made the break to become a leading light in the Australian Association for Cultural Freedom (AACF), and the Asia Foundation, both local branches of wider global CIA fronts.

As the cracks preceding Labor’s 1955 split began to appear in the party, Kerr was sought as a candidate by both factions of the party — and later by both DLP and ALP, but thought the Catholic right was going nowhere and that his one-time hero Doc Evatt had failed to flush out communism from the main party. A failed tilt at the AACF presidency appeared to add to what was a growing bitterness at how things had turned out.

None of this should be seen through the smoky prism of the later Sir John Kerr, stumbling around the Melbourne Cup in top hat and tails. None of it was yet a desperate and cynical grab for influence.

Had he wanted that, he could have joined Labor in the 1950s, where he might have been a rival for his friend Gough Whitlam. The Whitlam and Kerr families had holidayed together in the ’50s; both would remember a beachside discussion in which Whitlam made clear that he would stick with Labor despite some Communist entryism, which he saw as minor, and the Communist party as already fading. Kerr made it clear that he could not, and that the issue was a world-historical one.

Such conversations were had across the western world in the decade by people who had found themselves caught up in great events and great human possibilities, and tragedies and crimes, and had to make some fundamental choices. But there was also a difference.

Whitlam wanted to sewer the outer suburbs of our big cities and get every kid his own room, desk and lamp to do his homework with; Kerr wanted to be part of Great Events.

Whitlam was happiest with a Hansard and a report on rail electrification prospects; it is Kerr who had read Hegel. And it’s not as if history was not reaching out to Australia — the 1954 Petrov Affair, in which a senior Soviet attache defected and his wife was nearly abducted back to the USSR, kicked off both the Labor split and the intense hunt for a “third man” spy in MI6, sending the CIA into 20 years of counter-intelligence paranoia.

But after that Australia settled into an early rehearsal of suburban post-histoire, and Kerr and others were faced with the dilemma: this was the peaceful, democratic, mildly socially progressive West they said they wanted.

Yet for those who had been made by history in the 1930s, it was a kind of death. For those who had suffered actual history it was a kind of paradise. (Migrants made Australian suburbia because they had landed in a place where no one was trying to shoot you for your surname. Boredom was the gift of life.)

By the time the NSW Liberal Party reached out to Kerr the muscle had turned to flesh, and the man had turned to drink. He was rescued from penny-ante legal work by Sir John Carrick. Carrick was a working-class boy, Changi survivor, and former aide to Lord Mountbatten who saw the Liberal Party as a vehicle for steady progressivism, and built much of the NSW party’s infrastructure (and mentored John Howard, inter alia).

He was also an advocate of the independence of the Senate. Carrick tried to persuade Kerr to seek Liberal preselection, arguing that that was where his politics now lay; instead he helped Kerr get a judgeship on the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, and then to become chief justice of NSW.

From the Palace Letters we know the man that Kerr had become by the time he was knighted (on premier Robert Askin’s recommendation) and had become governor-general in 1974. If you think these letters would be too dry to read, think again.

The correspondence forms a sort of cubist portrait of a man desperate not to be respected, or loved, or liked, but first and foremost desperate simply to be.

The letters are the clinical notes of a man in deep bad faith, someone who has been offered a role which will define him, and takes to it with an embarrassing urgency.

Many people reading them have noted an unmistakeable tone of neediness, the great man become a crushed boy. What did a bewildered palace make of his six-page single-spaced disquisitions on the honours system, the relevance of the curtsy, the Australian people’s love for Princess Margaret? My God, on and on he goes. The former radical sounds like a courtier in the Freedonia of Duck Soup, from Stalinist to Marxist, tendance Groucho.

A generation of people, young or youngish at the time of the Dismissal, seeing a future ripped away from them, have a white-hot anger at the man Kerr by then was. He has come to be portrayed as someone whose life was a mewling, puking hunt for those honours. I do not believe that for a second.

This was the least of consolation prizes for someone who had been part of history; this was, at least, something, when the alternative was nothing at all.

Saying that Kerr staged the Dismissal by ambushing Whitlam simply to get into history doesn’t answer the question: get into history for what? People get into history via the Guinness Book of Records, if they have no reason to want to be part of it. Kerr’s great good luck was to have a crisis on his hands, which was of a continuity with the great struggles of Australia’s past, and a continuity with the man he had once been — the history hungerer.

Well, we have previously laid out the arguments as to why Sir John Kerr would have unilaterally sacked the government weeks earlier than required: a belief that the Whitlam government had to go then, precisely because the Coalition’s Senate vote was about to crack and cause his ’60s-era associate Malcolm Fraser a loss he would not survive; a need to kill the loans affair, whose billion-dollar search he had probably accidentally, illegally signed into law in 1974; a residual suspicion that Whitlam’s government was being manipulated by the Communist Left, which was wrecking the power of the intelligence agencies; Whitlam’s explicit threat to not renew the leases on US spy bases, due December 9; his threat to reveal in Parliament that the Australian permanent defence establishment knew of CIA agents in-country; a telegram from the CIA threatening the end of intelligence sharing if such proceeded; the threatened “social revolution” of the 21 bills held up by Senate obstruction, which included the first stage of major resources reclamations from private speculation; a desire to uphold the “reserve powers” as a living principle, and thus make a stand for the palace “firm” he had become part of; and the fear that Whitlam would remove him first — and this last feint at history would end in absurdity afresh.

There is no way of determining what role these different motivations played in Kerr’s decision, because the idea that there is a stable order of such out there somewhere is a fiction of who we are and how we act.

It was always manifestly absurd to simply reject the notion that a former radical would not be drawn to a radical act in the name of its opposite; or that a CIA client actor would not have as a consideration Australia’s role in a crucial feature of the West’s cold war armoury, and its position within the Western alliance altogether.

Now, Kerr’s letters make it clear that ignoring such factors is wilfully bad history, falsification, propaganda.

Between November 3, November 11 and November 20, when he wrote an account to the palace, Kerr’s way of speaking about the crisis manifestly changed — from regarding it as a political stoush, founded on Senate “deferrals” with weeks to run, to a national crisis created by Senate “refusals” which had to be resolved.

That was simultaneous with Whitlam’s refusal to back off naming CIA agents in parliament, and refusal to guarantee the lease-renewal of the bases. Any genuine future history of the Dismissal will have to include that.

But of course any future history of the Dismissal will have a different aspect to it than previous. The 50th anniversary approaches. By then, anyone with a childhood memory of it will be near their sixties; as an adult, their seventies. To many in younger generations it has become a cliché of the boomers, their thwarted accession.

But that will offer a chance to tell it more completely, as part of a history not only of the post-war Cold War, but of the century itself, inaugurated by the Bolshevik Revolution; presenting the most radical possibilities for humanity’s self-possession while flinging it into the abyss.

The Whitlam government got there too late, and it was all too rushed and haphazard. So there is always a degree of fantasy in pondering Rex Connor’s plan to buy back the resources sector, run it for national benefit, plough the money into a home-grown uranium industry which would create energy verging on a free good, and thus bootstrap the country still further.

With two full terms, with Whitlam elected in 1969, with that plus a social program, would we have become the Norway of the South, with a multi-trillion dollar future fund?

Who knows, but what we wouldn’t be is the giant bubble we have become where people who can’t afford a house on their thieved hospo wages are told they live in the greatest country in the world, where you need a degree for everything but it will cost 50 grand, where the poor and precarious have been cut loose, the environment has been wilfully destroyed by deliberate neglect, the major media is a property of intersecting right-wing cabals, the universities have been destroyed from within and without, and a local culture has been allowed to fade and die in favour of Netflix and a US film lot.

Yes, it could have been different, and the reasons why it wasn’t so probably happened earlier than the Dismissal.

But that set the seal. The Fraser government renewed the bases, inaugurated the ECHELON program — the true precursor of the current NSA total surveillance system — re-upped the spy agencies’ powers and money after the 1978 Hilton bombing, and sold off the farm.

Labor’s internal wars saw the right come out on top. When they explicitly renounced an independent foreign policy and national buy-backs, the Murdoch press dialled down its anti-Labor rhetoric, and they won the 1983 election.

The final act? The late-’80s, early-’90s Hawke-Keating privatisation of a series of natural monopolies which had under-girded Australian social democracy, and the gifting of The Herald and Weekly Times to Murdoch, which did for us media-wise.

If we look back at it again and again, it’s because it is a tragedy, and it could have been otherwise.

Look back not for nostalgia or consolation, but because it is only in understanding that full contingency of history that we grasp the future, and the possibility of making it.

John Kerr entered history, but not in circumstances of his choosing.

A country without history? Just look at it! John Kerr, nothing other than a top-hatted buffoon? No, he was Australia and the 20th century — all the squalor and hope and absurdity of the times in one life.

He got his reward and his punishment, stumbling around a racetrack, jeered at by stadiums of people, the fool to his own Lear, profitless in the desert he helped make.

Guy, this is a really interesting read, thank you. I was unaware of a lot of Kerr’s associations in his early days and while I am aware of, and have read extensively about the Whitlam dismissal, this was a refreshing look at things. Cheers, Chris

Laurie Short!

Yes, I thought so too … last I noticed Laurence Street was a judge and Lieutenant Governor of NSW ….

See you and raise you an Eveleigh!

Nice work, GRundle.

To those who were around to see it, I thought Kerr’s alcoholic Melbourne Cup oration was one of those choice moments when the veil is temporarily lifted on the sanitised image of a problematic A-Lister.

The oration was gold but the GG’s footwork was something else again.