Banks were instructed by the banking regulator earlier this year to not pay dividends to their owners, but instead hoard those profits as defence against running out of capital. It sent a signal that the regulator was deeply concerned about the health of Aussie banks.

That rule has since been loosened, but the risks are far from over. Aussie households are hanging on for now, but as Christmas approaches income support will be removed and then early in the new year banks will start to demand loans once again be repaid.

So what will happen to Australian banks during this recession? They stand behind trillions of dollars worth of loans in this country, and many of those loans are still at risk. The biggest category of loans Australian banks own is mortgages, and they have performed so well for so long that it is worth worrying that banks may have become complacent.

With falling migration rates and a shrinking economy, it is rational to expect Australian house prices to soften. Louis Christopher, of property research firm SQM, has warned of a possible 30% fall. A sharp crash of that magnitude would be bad enough for Australian households, damaging their wealth and thereby affecting their spending, but it would be even worse if it propagates into a financial crisis that sends Australian banks to the wall.

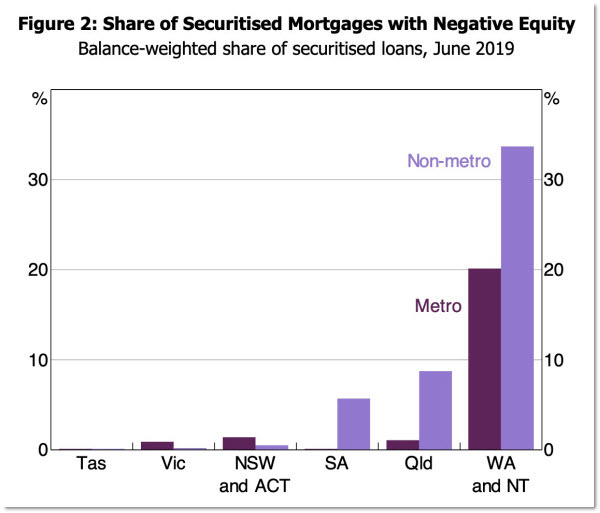

The next graph shows the share of mortgages in June 2019 where the owner owed the bank more than the house is worth, what they call “negative equity”. In rural Western Australia and Northern Territory, that figure was almost 30%. In Perth and Darwin, 20%.

The eye is drawn to those tall bars in the graph, but from the perspective of Australian banks’ balance sheets what matters much more is the short bars on the left. The share of mortgages in negative equity in Victoria and NSW is extremely small, despite the correction in house prices during 2017-18.

The idea that negative equity will spread to the capital cities and then bankrupt the banks is a popular one among a certain segment of gloomy forecasters.

Mortgage defaults hurt banks because they end up owning an asset that is worth less than the loan on that asset, and they make a loss. Defaults have actually been fairly rare in Australian history, largely because house prices have risen so steadily. If house prices enter a broad-based correction, what will happen?

If house prices tumble, do people immediately default? New research from the Reserve Bank of Australia suggests it is more complicated than that. Using a dataset of nearly three million loans, including mining regions with high instances of default, they find very little evidence people default “strategically” on their mortgages.

“Early studies focused on ‘strategic defaults’, framing mortgage default as a rational response by borrowers to negative equity,” writes the study author, Michelle Bergmann.

“As more loan-level data became available, empirical studies called the predictions … into doubt. Far fewer borrowers defaulted than … predicted, even at very high values of negative equity.”

People might owe more than the house is worth, but we keep paying that mortgage off anyway. Defaulting is not costless — it means you have to move house, it harms your reputation and it does horrible things to your pride. People generally want to hang on to that house.

“The median US non-prime borrower did not strategically default until negative equity reached 70%,” writes Bergmann.

Mortgage default requires a “double trigger” says Bergmann. Owing more than the house is worth is not sufficient for people to default. Neither is losing income. But when both are present, the risk of default goes up enormously.

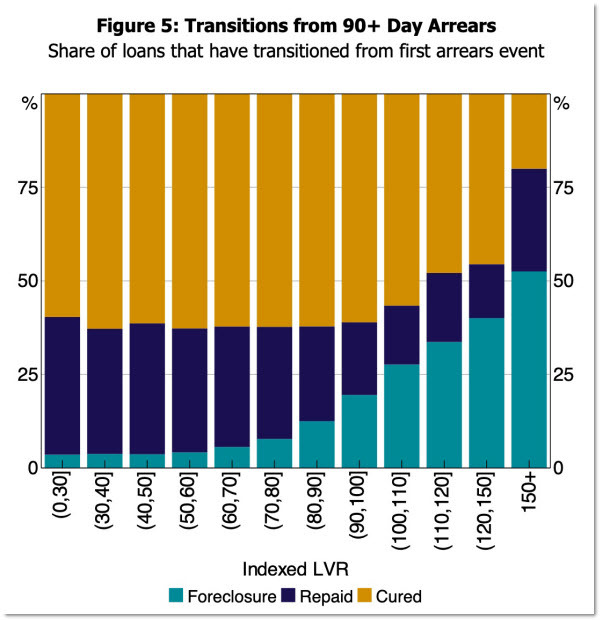

The next graph shows what happens to loans which are already in arrears. They might foreclose, be repaid (by selling the asset) or “cured” which means the repayments get back on track. The horizontal axis shows the loan-to-value ratio (LVR). At the right hand side is a loan to value ratio of 150+, which implies owing 50% more than the house is worth.

It turns out that if you owe $1.5 million on a house that’s worth $1 million and your repayments are already in arrears, you have an over 50% chance of defaulting — being foreclosed. Then the bank owns the house and it has to deal with the loss.

What we need to be worried about is a double hit — if house prices start to fall, then the newest loans will sink into negative equity. If unemployment is also high, some home-owners will be unable to repay. Some of those loans will satisfy the “double trigger” criteria and will default.

This is not America in 2008. The housing bubble can, potentially, pop without creating a financial disaster. But if employment crashes in the same places where house prices are tumbling, then we need to be extremely cautious.

“…defaulting — being foreclosed. Then the bank owns the house and it has to deal with the loss.”

I’m no expert, but I seem to remember from the GFC that this was the case in the US, but here the defaulting owner still has to continue paying what they owe. Is this wrong?

Correct, Woopwoop. In the US your debt is nullified when you hand the key to the bank. (Note that in the US, interest paid on mortgage is tax deductible – as with negative gearing but on your place of residence as well as any investment properties.)

In Australia, the mortgage stands until paid off. Provided your income is still sufficient to cover the monthly payments, and since you still need somewhere to live, you just stay where you are, keep paying the mortgage, and hope that inflation or rising house prices will eventually put your head above water again.

If your income drops to a level that makes the monthly repayment impossible, you sell the house, pay the proceeds off against the mortgage, and continue to pay the difference between the sale price and the mortgage amount until it is paid off.

Needless to say, the first option is less worse.

DF – Correct up to a point, but only in the case of non-recourse mortgages in the USA do you get to hand the keys back and walk away. If you’re an American and you’re one of the minority of borrowers who’s negotiated a typical recourse mortgage as we’re forced to do here, then you’re just as likely to try and ride out the downturn as we in Australia are.

MoC – thanks. Can you pls explain what are recourse and non-recourse mortgages?

Asking for a friend.

Non-recourse mortgages are where the bank cannot chase you personally for any outstanding balance owed on the property after they’ve foreclosed and sold it. With a recourse mortgage they can chase you for eternity or until you’re declared bankrupt, whichever comes first!

We have almost 100% recourse mortgages in Australia while most Americans have non-recourse ones. Also in Australia, if you have less than an 80% deposit your bank will force you to buy Lenders Mortgage Insurance, which means that the bank WILL get paid by that insurer for any shortfall after the mortgagee sale, and then the insurer will chase you for eternity for that payout, or until you’re declared bankrupt, whichever comes first! What a system eh!

This is a very poorly written piece. A default occurs when the mortgagor (owner) fails to pay and amount due under the terms of the loan. A breach of covenant occurs when the mortgagor there is a breach of a term of the mortgage by the mortgagor, eg when the amount of money owing under the mortgage exceeds a specified percentage of the value of the security (ie the house). The mortgagee has a range of options under the mortgage when either a default or a breach of covenant occurs, one of which (after certain preliminary steps) is to realise the security (ie sell it and use the proceeds of sale to pay the mortgage debt or as much of it as possible. (Realisation in these circumstances is now often called foreclosure in this country, although foreclosure technically is something else. It’s better to talk of a forced sale.)

As a matter of fact, one lesson that the banks learned back in the “recession we had to have” in the early 90s is that most homeowners will do everything they possibly can to meet their mortgage repayments, and that house prices will always (with hardly any exceptions) eventually rise over time; so it’s usually not necessary to force a sale merely because the owner has missed one or two payments or the house has gone into negative equity. In fact, selling when there’s negative equity is often the silliest thing the bank can do, because by doing so it will lose that equity shortfall forever, whereas if the bank sits tight the value of the property will eventually recover and indeed exceed the amount of the mortgage, and the mortgagor will eventually pay the debt in full, including interest.

One other thing, one of your charts has a heading referring to “Securitised Mortgages”. That’s a term with a specific meaning, and only quite a small proportion of mortgages are “securitised”.

Thanks Robin, and others, clarification quite useful.

Though I’m not sure the banks and the owner can rely on the ever growing house prices solution if a bust comes to pass.

On a related point, an economy that is completely dependent on increasing house prices is one built on sand. Methinks the desperation for continued population growth is less about the effect on GDP, and as much about the predicament we find ourselves in, relying on growing house prices or the economy gets it. Imagine holding a gun to your own head and shouting ‘anybody moves and he gets it.’

Mel Brooks, Blazing Saddles.

I don’t know about the “built on sand” thing. The sand has been pretty solid for a very long time. Of course I’m talking about “the long run”; within a shorter period it’s very possible to lose money on real estate. My wife and I bought a house in 1981, which, unbeknownst to us, was the tail-end of a boom. I would say that for the next 4-5 years it was worth less than we paid for it. We never got to the point where it was worth less than the mortgage, I’m glad to say. Five years later again, in 1990, after another and extremely spectacular boom had been and gone and we were again in a property down cycle, we sold it for over three times what we had paid 9 years earlier.

“Defaulting is not costless — it means you have to move house, it harms your reputation and it does horrible things to your pride. People generally want to hang on to that house.”

Further to that, good luck trying to get another homeloan down the track.

I can’t think of any ‘strategic’ reason why someone would default (unless they plan to plan to pull a Christopher Skase which would be particularly difficult at the moment).

As mentioned in the article, it is not in any parties interest to default so the only logical position is to hold as long as you can with defaulting the option if you have no other choice.

It looked a lot like the reserve bank was buying mortgages off the big end at book value as a liquidity measure.. wasn’t that the cause of the major uptick in their stock prices about a month ago.. it seemed to be a movement in the to big to fail direction last seen in the GFC..