Australians are dipping into their super funds like Winnie the Pooh sticks his paw in a jar of honey. The Australian government decided to let us take out up to $20,000 in two bites. Millions of people didn’t need to be asked twice.

The official estimate for the amount removed from Australia’s retirement savings system is now a whopping $42 billion.

According to ME Bank — a bank owned by super funds — the group most likely to raid their super are those aged 18-24. 30% of them dipped in compared to a population average of 8%. Because of the magic of compounding, the effect on retirement incomes in this group is much higher than the effect on a person with a shorter period until retirement.

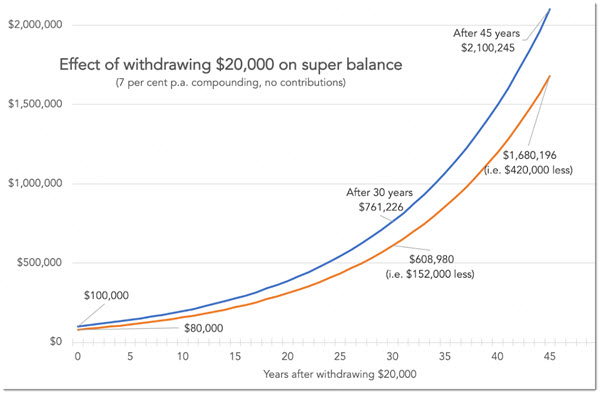

The way compounding works is via a kind of curve we are all familiar with by this point of the pandemic: an exponential one. In each time period the increase is higher, making the curve turns towards vertical at the right-hand side.

As the next graph shows, a 20-year-old with 45 years until retirement could have expected $20,000 in superannuation to turn into $420,000 extra in retirement. Whereas a 35-year-old with 30 years until retirement could expect that $20,000 left in super to turn into $152,000 extra. The longer you have until retirement, the more those few dollars matter.

Sounds simple right? Young people should just have patience! Let’s look more closely. This graphic makes a couple of assumptions.

First is that young people would have $20,000 to withdraw at all. Now, I set the starting point at $100,000 so the curve illustrating the effect of withdrawing funds starts at $80,000. That starting point doesn’t change the difference between the two scenarios. You could do the comparison between having $20,001 or $1 in the first year and the difference between the lines would be the same.

But even having $20,000 in super to withdraw is very rare for young people. The median person aged 15-24 has just $2500 in super.

What that means is most 18-24 year olds given the opportunity to clean out their super fund of $20,000 will have left the cupboard bare. And no matter how magical the magic of compounding might be, you can’t create an exponential curve if you start with zero. Young people who clean out their superannuation during the pandemic will be starting from scratch when, or if, they next find a job.

Superannuation is seen as very democratic. But it is not evenly distributed at all. The median super balance for all Australians was $65,000 for men and $45,000 for women in 2017-18. Does that shock you? It’s not what all those glossy AMP ads would suggest is normal.

The average super balance in Australia is $169,000 for men and $121,000 for women. The average looks much higher than the median because superannuation holdings, like most wealth, is concentrated among the top end. Meanwhile, millions of Aussies have literally zero in super. The uneven distribution of superannuation in the community means realistically, the aged pension is unlikely to go away. Even in 2065, people who chased their super down to zero in the pandemic will still have access to a pension. They’re not going to be on the streets.

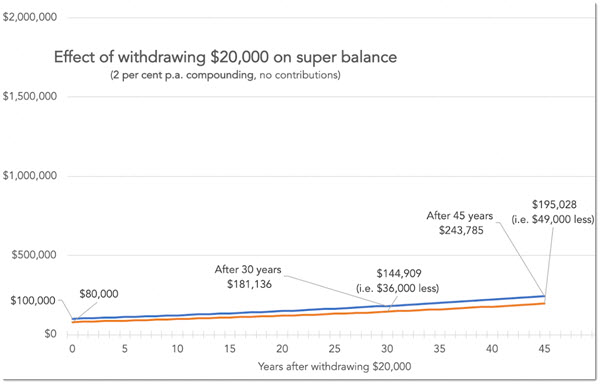

The second assumption in the graphic above is the rate of return. This is vital. I chose 7% because that’s been a historic norm for investing. But what if it isn’t accurate? If the return is lower, the apparent penalty for withdrawing funds is much lower.

As the next graph shows, with 2% returns for the next 45 years, the penalty for withdrawing $20,000 now is just $49,000 in 45 years time. I’ve used the same scale as on the graph above to make the comparison stark.

In a low returns world, there is much less advantage to saving. Taking out $20,000 now makes far more sense. This is the fact we all must wrestle with.

In general, the chocie to consume now or consume later — whether to save or borrow — depends on our own preferences. I can borrow, moving consumption from the future to the present. Or I can save, moving consumption from the present to the future. How do I make these choices?

Most people would prefer to consume now, all other things being equal. This is why we pay interest on savings — you have to offer some reward to get people to defer consumption.

How much return do you need to be motivated to save? It depends on what they call a discount rate. This varies by person. Do you need 1% a year? 5%? 7%? It can swing wildly depending on your circumstances. Your discount rate might shoot up if you lose your job, for example. After all, you need to eat and pay your rent in the here and now.

Official interest rates are at zero. The federal government is borrowing billions of dollars for 30 years at under 2%. It may be rational to assume long-term returns will not be high. If your personal discount rate is 3% and you expect returns on your super to be 2%, raiding your super makes perfect sense. This is the reality facing young people; income loss in the here and now, plus low expectations about the returns on saving.

The history of the Australian stock market has been one of high growth, but as the super funds tell you in the fine print, past performance is no guarantee of future performance. In Japan, the Nikkei index remains below its 1991 levels. Trying to save in that context has been a fool’s errand.

It is easy to moralise about young people raiding their super. But it may be that doing so is the rational response to the world they face.

It’s not a moral issue about young people withdrawing all of their super. I’m in my 50’s and acutely aware of my retirement savings, but given the chance in my 20’s, I would not have hesitated to pull out my super and spend it on something more pressing.

The moral issue is that the LNP Govt knows this. They will also know that the $42billion drawn down will have a cost in multiples – what $300 billion or so in retirement savings? And that will need to be picked up by taxpayers. The same taxpayers who the LNP keeps promising lower taxes.

Interesting maths.

The only math the LNP cares about is gutting the super industry. They know they’ll all be long retired or dead by the time the massive bill for their bastardry comes through…

Dead right. Would it be drawing too long a bow to suggest that the reason the government provided not one razoo of assistance for the vast army of casual (sorry “flexible”) workers was for the purpose of weaponising their poverty against the industry super funds to which most of them belong? The LNP and their owners have feared the growing capital accumulation of the industry funds for years and have been trying every trick in the book to destroy them. Covid gave them a perfect opportunity – the lives and precarious livelihoods of the poor bloody casuals are dispensable in the fight against one of the LNP mortal enemies.

Of course none of the LNP brains trust considered that casuals would continue working, thus spreading the virus to rich and poor a like, because they have no other choice.

Well, Jason, as a single woman who’s just hit 60 and who only earned what might be described as a higher income in her mid 50s for less than a decade, I can tell you that I now deeply and bitterly regret withdrawing $10,000 from my then employer’s extremely generously supported super in the late 80s. This shortsighted move has created a six figure deficit to my modest super balance. And, having been unemployed now for a year, unless I can find a job that will enable me to contribute at least a little more to that balance and for at least the next seven years (pension eligible age), the going is gunna be bloody tough in my old age.

Did the LNP Government fully considered the consequences of this move in terms of creating an even larger underclass of aged pensioners some decades down the track? I think not. All caution and sense and concern for the future well-being of a couple of generations was thrown to the four winds as this opportunity to attack our super system was manufactured out of the pandemic.

Sensible piece. It ought to be remembered also that many people aged 65 have only had any superannuation since 1992 when it became compulsory. That is, they were about 37 before they began to accumulate any funds. Today’s young people may still end up with larger balances than many older folk. A bigger problem is the introduction of fees for tertiary education, requiring them to take out loans to be repaid over many years. In a rich country like ours higher education should be free again. So, instead of complaining about the hit to tiny super balances, those who really care about the fate of the young should be campaigning for the abolition of tertiary fees and HECS debts.

Good to see some nuance and maths in this piece Jason. Yes, it’s much less clear cut than some imagine.

Also, the average amount taken out of super. for the 15-24 age group was a tick over $2000, so likely there was nobody in that bracket taking out the full $20K, and if they did it is likely they’re in a well paid gig and will more than make up for it over 40 years.

Also, the 7% return, on average, that superannuation companies like to sprinkle widely through their prospectuses are close to unachievable for the next decade, and anyone invested solely in high growth will probably lose much more than that if we see what looks inevitable to me, a substantial stock market correction bringing it back to planet earth and a subsequent longer term recession and possible depression.

If we get 7% returns over the next 10 or 20 years I’ll be very surprised indeed. I’ve left work recently and have parked everything in cash and bonds. The worst time to experience a stock market correction is immediately after you’ve retired. Strangely I have seen only one reference to that academic study in the MSM, and even more surprising is that my industry superannuation group didn’t think to inform me at all. I don’t think they even knew.

I received gobsmackingly bad advice, in my opinion. Luckily I have been following what’s happening in the world and was in a place to make my own decisions.

The kids are alright, and if they used it to pay off credit card debt and then tore up the credit card it would be the best investment they have ever made.

There is a public policy perspective and an individual perspective. From a public policy perspective, superannuation can save the government from funding retirement through the old age pension. It can also be argued that the pool of funds invested boosts the economy (though consumption also boosts the economy). To what extent these objectives are achieved is debatable, but it is presumably the motivation for providing tax incentives, however poorly designed, for superannuation.

From a personal perspective, the tax incentives can’t be ignored (though they are less valuable at lower marginal tax rates). So it is not just a case of comparing consume now, with save and consume later, it is a case of consume now vs invest in super with tax incentives and consume later vs alternate investment and consume later.

Ian, this is wrong. Superannuation costs both society and the government far more than an aged pension funded from taxation. The tax subsidies for taxation of superannuation already costs the government more in revenue not recieved than the old age pension in expenditure outlays. These tax subsidies used to be counted as ‘tax expenditures’ by the government, but this was changed because it didn’t look good as most tax expenditures are really welfare for the rich. Further the superannuation industry in fees and commissions cost the Australian economy billions a year. According to Richard Dennis of the Australia Institute this is billions per year, roughly equivalent to what the government spends on the military each year. Most of this massive unnecessary cost is avoided with a tax funded aged pension scheme. It is a just a burden or deadweight loss on our economy.

The argument about investment is also wrong. Usually it is argued that compulsory super increases savings. Empirical evidence is that it doesn’t. For all but the poor who have no choice, Compulsory superannuation savings can, and usually are, offset by people borrowing more. It does not increase savings or the pool of money available for investment.

Also, most people consume their superannuation Reasonably quickly after retirement and then still go on the old age pension.

There is also a good argument (though I’m not aware of empirical evidence) that compulsory super encourages bad or poor investment decisions. This has two parts. First is that those on the superannuation industry are investing ‘other people’s money’ and are less likely to make the best decisions for those people. Just like institutional aged care, institutional financial management is likely to be just as bad. All care, no responsibility. Hence you have the spectre of investment in extremely unethical businesses, tobacco, infant formula etc. The second part is where individuals are having to manage their superannuation. My sister, a nurse, was spending hours each week looking at the stock and money markets worrying about her superannuation. She was a very highly educated and proficient nurse, but she knew nothing of financial markets….. and nor should she. In essence the superannuation system imposes quite an unnecessary time costs on her.

You are correct that there is a difference between what an individual should do versus public policy when it comes to superannuation. Like other commentators I’d have to agree that superannuation is a difficult decision given the uncertain future, uncertain non-guaranteed returns if any from super, the loss of the aged pension due to means testing on retirement versus the generous tax subsidies. From a public policy viewpoint it is exceeding difficult to find supporting argument except perhaps the Hawke/Keating line that superannuation provides a non-inflationary wage increase and (for industry funds) involves labour (union officials) in investment decisions usually made by capitalists, or the moral argument put forward by the Liberals when confronted with the evidence that Australia’s superannuation system doesn’t increase savings and is just a big welfare for the rich scheme, that it is an ‘incentive for thrift’.

Don’t think it us about saving the government from funding retirement through the aged pension but in fact making the aged pension sustainable for those who really need it.

Why? It may seem counter intuitive to the narratives in Australia, but we have a burgeoning number of retirees in the permanent population with a proportional decline in the working age population, both are support by temporary churn over of net financial contributors.

The alternative to superannuation and/or crashing the aged pension, is raising taxes on the working age population, taxing more retirees while decreasing services and benefits, like the aged pension.

Australia is in the top five of most sustainable pension systems in the world along with Canada, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland; not a bad club to be a member of either.

https://www.worldfinance.com/wealth-management/top-5-most-sustainable-pension-systems-worldwide