The big economic topic in Australia is always house prices. Always.

House prices affect everything, from the number of bodies huddled on our streets at night, to the strength of the consumer economy. Australia’s banks are all heavily exposed to mortgages, so house prices undergird the stability of our whole financial system.

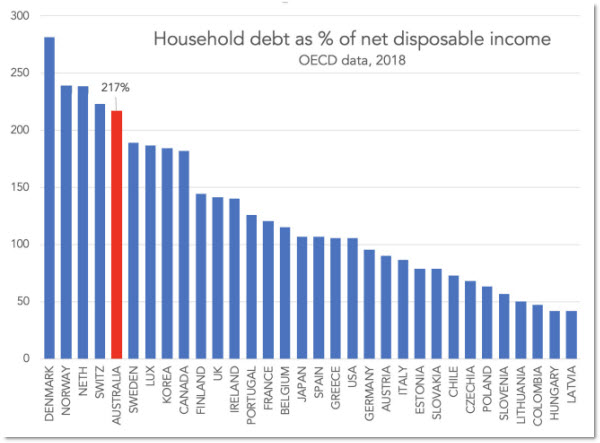

Rising house prices have sent Australian household debt up and up, creating a staggering ratio of debt to income.

OECD data shows our household debt is among the highest in the world.

Debt is always risky. If it can’t be repaid, both the borrower and the lender lose. That is why Australia’s mortgage mountain is one of the biggest economic concerns during the pandemic.

If people lose their jobs, they won’t be able to service their mortgages. If they can’t pay their mortgages, they are forced to sell their home (or the bank repossesses it and the bank sells it). These sales would happen in a weakened market, making the situation even worse.

To avoid unnecessary forced sales in a weak market, banks have been offering loan deferrals. In the bad times, they’ve offered an option to defer repayment – for an initial six month period that will expire in September, and then an option to extend to March.

Almost 900,000 Aussie borrowers have taken them up. But it can’t last forever.

There is no shortage of pundits and observers who are extremely bearish on Australian housing. People who will tell you the entire Australian economy is a housing Ponzi scheme and the big four banks are moments away from implosion.

These people have taken some big hits in recent decades, but right now their arguments have more credibility than ever. I remain tempted by some of what they say, but I also refuse to become untethered from the facts on the ground.

What is happening?

Last week we got a lot of new facts about the housing market, courtesy of two big banks. Both CBA and NAB released useful data on home loan deferrals.

Each released different kinds of data. CBA, in its full year report, gave us a shallower glimpse into their loan book, and made things look reasonably good. NAB, in its third quarter trading update, gave rather more detail, and in doing so revealed a few places where things look a bit grim.

First, to CBA — Australia’s biggest lender.

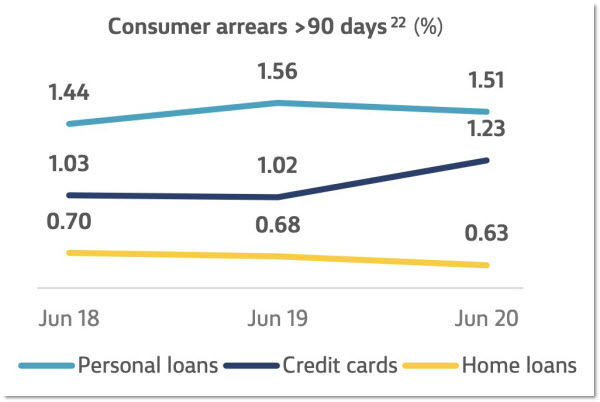

The good news from CBA is that home loan arrears are down not up. That’s a pretty spectacular achievement in an environment of rising unemployment and sinking wages.

Also, only 8% of their home loan customers had deferred their loans. Of these customers, the bank assessed 12% as being “high risk” and a further 26% at some risk level.

The ratio of the size of the home loan to the value of the house is an important metric for home lending. Ratios above 100% are risky.

They can be caused by lending to customers with small deposits who then see values fall. Two-thirds of CBA’s deferred customers had ratios below 80%, meaning they owed at most say $400,000 on a $500,000 home.

Overall the CBA numbers should be taken with a grain of salt, but they give some hope – at least at this early stage. The NAB numbers are slightly different, although it is hard to be certain if they are performing worse or simply being more forthcoming.

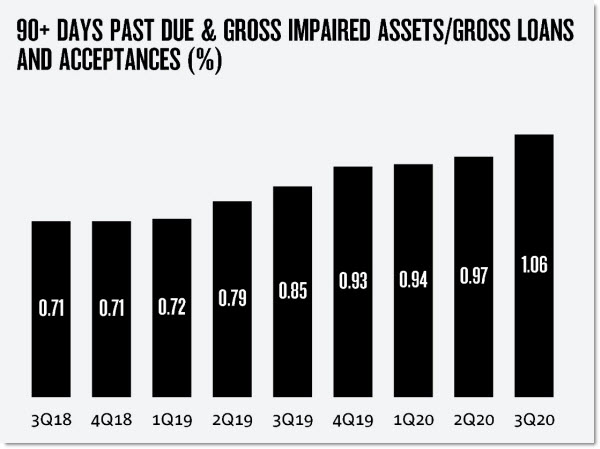

NAB loans impaired and past due are up slightly, but at just over 1% remain low by historical and global standards.

NAB has $92 billion in home loan deferrals, compared to $48 billion reported by CBA. And some of its customers are in serious strife.

“Analysis of deferral customers with NAB transaction accounts indicates ~20% with >50% decline in salaried income since the start of April,” the bank wrote in its supplementary disclosures, released on Friday.

With employment dire nationwide and especially bleak in Victoria, you have to worry about those loans. Who can pay off a home loan when their income is halved?

Of course, borrowers with small deposits are required to get loan mortgage insurance, and NAB has only $4.5 billion in deferred balances where the borrower has no such insurance and they owe more than 80% of what the home is worth. Some of the pain will be passed on to insurers.

Another slightly concerning statistic released by NAB – their deferrals are mostly in large loans. While only 14% of their home loans are over $1 million, those loans represent 21% of deferrals.

But for some arguably good news, it is owner-occupier loans that are over-represented among deferred loans, not the more volatile investor loans. Interest-only loans are also under-represented among deferred loans.

What happens next?

This is not the GFC. Major Australian lenders are extremely unlikely to go broke – largely because of the lessons of that crisis. Banks are frequently stress-tested and they are stuffed with capital such that they can withstand a downturn.

NAB still reported a profit of $1.5 billion in the 3rd quarter. CBA reported a statutory profit of over $9 billion for the financial year. They have plenty of buffer even before the government has to step in. That is not to say that all smaller lenders and property finance companies will make it out intact.

What the data show most clearly is a small — but not insignificant — share of people struggling with their home loans. Markets are affected by what happens at the margin. If the 12% of CBA’s high risk customers have to sell at the same time as the 20% of NAB’s customers who have seen their salaries tumble, that could be enough to tip the housing market downward.

Hooray? The frustrating thing about a falling housing market is it doesn’t just represent cheaper homes for young people.

It also affects the incomes of the many people who work in the housing industry and related industries. The RBA got something of a rude shock in the 2018 house price downturn when it realised how much of Australia’ economy was geared to housing.

Economists are already revising their estimates of the shape of the downturn from a short sharp downward spike to a long grind. It seems likely a downturn in housing will make the economic recovery slower and even more drawn out.

“The RBA got something of a rude shock in the 2018 house price downturn when it realised how much of Australia’ economy was geared to housing. ”

So doesn’t this show that the housing market is indeed a Ponzi Scheme?

Whether or not the housing market is a Ponzi scheme, it is surely unarguable that houses in Australia are way overpriced?

Don’t ignore demographics, i.e. not ‘immigration’ or ‘population growth’ based upon temporary churn over, especially major cities, but in our permanent population across the nation including regions.

Oldies living longer and now baby boomer bubble transitioning to retirement which would suggest significant downsizing etc. to occur over the next generation but no such significant demographic bubble to follow in gen x etc.?

The is whistling in the dark, to keep up courage, identical to the nonsense about the economy getting back to growth.

Ain’t gonna happen.

And, if we expect to maintain civil society, shouldn’t.

“Australia’s banks are all heavily exposed to mortgages, so house prices undergird the stability of our whole financial system. “

It’s been our problem for 30 plus years now, it was always a disaster. Love the line about the RBA being surprised in 2018 to realise. Where the hell have their heads been?

Of course it’s a Ponzi scheme, it’s just one that will take longer to play out. Whatever else, it is a huge drag on the economy as so much of wages goes to repaying housing debt rather than living.

But our brainiac politicians thought rising house prices were such a good thing, come on down Mr Howard and Mr Costello.

Has there been a Treasurer who knew less about economics than Costello?

I can’t think of one!