When sex discrimination commissioner Kate Jenkins delivered the landmark report into sexual harassment in Australian workplaces in March, following an 18-month national inquiry, she said there was momentum for change.

“Australia was once at the forefront of tackling sexual harassment globally … Australia now lags behind other countries in preventing and responding to sexual harassment,” she wrote.

“There is an urgency for change. There is the momentum for reform.”

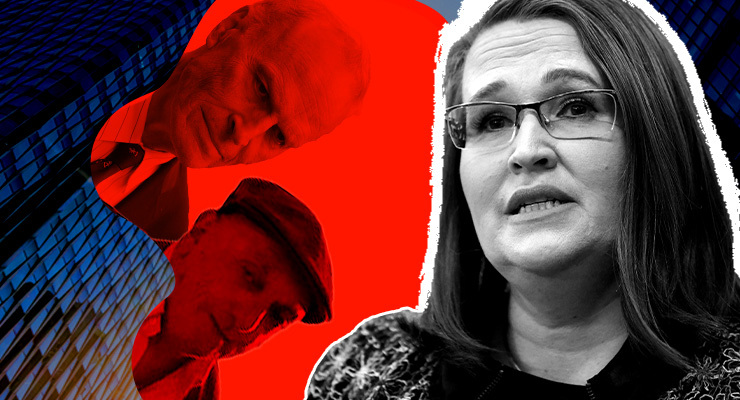

But six months on, momentum for reform has not led to monumental change. Sexual harassment continues on a serious, pervasive level and, as cases involving Canterbury League Club chair George Coorey, former AMP Capital boss Boe Pahari, and former High Court judge Dyson Heydon have shown, powerful men can face misconduct claims stretching back months and years — and when they are outed, they often get off with nothing more than a slap on the wrist.

Over the course of this week, Crikey will detail how the allegations against Pahari came to light, and how AMP didn’t take action until investors started pulling their money — showing just how removed the board was from what is expected by the community.

We’ll also look at the low rate of reporting in sexual harassment cases, analyse the ongoing mental, physical and career effects on victims, and examine how those at the top are often promoted instead of punished, encouraging a culture of harassment.

We’ll investigate what’s changed, and what hasn’t. The ’90s may have been decades ago, but many things are still the same now as they were back then. From boards stacked with members of the “boys’ club”, to allegations kept quiet, change has been superficial and slow to come.

Finally, we’ll ask a series of questions that often go unasked. Once a company knows about someone’s history of harassing colleagues, who — aside from the perpetrator — should be held liable? Is hiring more women to boards really the way to go? And why is sexual harassment still framed as discrimination, instead of a workplace health and safety issue?

Read part one of Crikey’s investigation here.

Its always good to be sure everyone fully understands, going in, the quoted headline figures from these reports. The most eye-popping one is I suppose this: ‘One in three people experienced sexual harassment at work in the past five years.’. That number is taken from the 2018 survey – 10, 200 ish people (15 and older) contacted by phone (40%) and computer (60%) and asked to self-report in response to questions based on a definitional list of potential sexual harassment behaviours as follows:

(ie Have you ever, in the workplace, experienced):

• unwelcome touching, hugging, cornering or kissing

• inappropriate staring or leering that made you feel intimidated

• sexual gestures, indecent exposure or inappropriate display of the body

• sexually explicit pictures, posters or gifts that made you feel offended

• repeated or inappropriate invitations to go out on dates

• intrusive questions about your private life or physical appearance that made you feel offended

• sexually explicit comments made in emails, SMS messages or on social media

• inappropriate physical contact

• repeated or inappropriate advances on email, social networking websites or internet chat rooms

• being followed, watched or someone loitering nearby

• sexually suggestive comments or jokes that made you feel offended

• sharing or threatening to share intimate images or film of you without your consent

• indecent phone calls, including someone leaving a sexually explicit message on voicemail or an answering machine

• requests or pressure for sex or other sexual acts

• actual or attempted rape or sexual assault, and

• any other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature that occurred online or via some form of technology.

I’m making zero comment at all, just clarifying what that headline ‘1 in 3’ number means: 1 in 3 out of a 10,000 sample said they have experienced one of more of those behaviours in the workplace, etc.

I don’t know where that desiderata came from but it is scary that the prime criterion seemed to be “feeling” not any overt fact.

Presumably it was written with the distaff side in mind but in these days of Heinz genders anything is possible.

It’s not that ‘feelings’ aren’t necessarily a legitimate benchmark – if people are ‘feeling’ harassed at work that has to be taken seriously. Where that shopping list (and the survey methodology) becomes problematic is in the classic ‘fridge door/light’ problem. The prospect that ‘opening the door changes the on/off data status’ ie…is that ‘1 in 3’ (crisis!!) statistic a reflection of an existing prevalence of harassment, or do you risk changing the data set by simply asking the question (complete with pretty wide-catching prompts ‘any other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature…’)?

I think this below is one of the real survey ‘tells’ re: that risk. The report notes that ‘workplace settings’ have a striking impact on the (self-reported) data. For example…:

‘Workplace settings where there is a higher risk of experiencing sexual harassment include those that:

– have been found by the 2018 National Survey to have a higher prevalence rate of sexual harassment than the rate across all industries of 31% (for example, the information, media and telecommunication industry and the arts and recreation industry)…’

When the report says ‘have a higher prevalence rate’ it actually means ‘self-reports having’ a higher risk rate. When you drill into the actual (self-reported) numbers, you find that in comparison to that 31% average (1 in 3) generally…81% (!!) of those in info/media/telecoms/arts/recreation ‘have’ (self-report at) a rate of over twice the national average. It doesn’t mean the behaviour they report is trivial, nor does it necessarily mean it isn’t a problem that shouldn’t be tackled. But it does highlight the profoundly circular, self-referential methodology of these kinds of ‘surveys’. The risk of existential self-justification; the risk of procedural confirmation bias…a dedicated Sex Discrimination outfit ever delivering a report into sexual harassment in the workplace that concludes ‘Not too bad, on the whole’ is pretty unlikely, I suspect.

It has always been the case throughout history that money and power could earn sexual favours .

Now mostly white boys club who feel entitled and above the law because they earn too much money.

its very hard to change conciousness v testosterone.

One is fighting human nature, as conditioned by a society that, in the broad, is far from kind and caring. Those executives who are caught out will, in many cases, find high-paying jobs elsewhere. Bank executives will often have the skills to do well as private investors. Their families, who get caught in the net, may suffer as much as they do, or more. Those in relatively lowly roles in an organization are likely to be much less well placed to get effective action than those in senior roles.

The ‘answer’, if there is one, lies in the creation of a kinder and gentler society, where wealth and position exercise a less over-riding role. The reality is that money talks, but it should not be all that talks. It does not talk for those in detention centers who are now at risk of losing their smartphones — which is just about all they have to get some limited contact with the outside world.