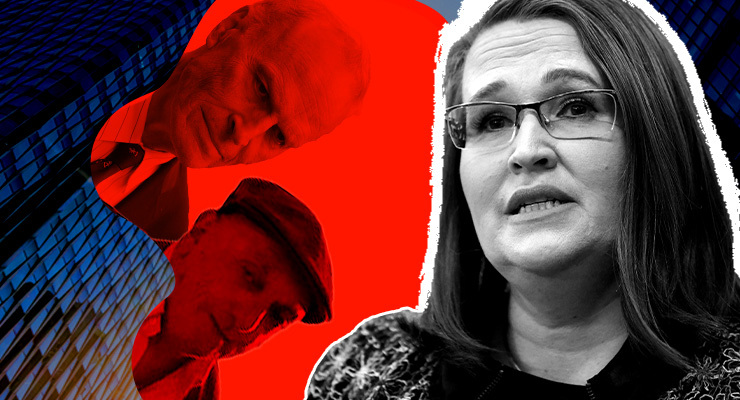

Three years before an Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) investigation found former University of Adelaide vice-chancellor Peter Rathjen guilty of sexual misconduct, he addressed a report on sexual harassment at Australian universities.

“We believe that one incident of sexual harassment is one too many,” said Rathjen, who was vice-chancellor of the University of Tasmania at the time.

Just a few years prior to this, he had been investigated for sexually harassing or abusing a student at Melbourne University — a fact he later tried to conceal from ICAC.

Sexual harassment is rarely a one-off — and not punishing the perpetrator only increases the likelihood they’ll harass again. Harassment is exponentially expensive for a company.

So when a complaint is lodged, who — besides the harasser — should be liable for fixing the culture?

We can’t fix what we don’t know

Those who experience sexual harassment rarely report it — and it’s no wonder, given the treatment of those who do. A 2018 national survey found that just 17% of people who had experienced sexual harassment in the previous five years made a complaint, while 35% of bystanders who witnessed or heard about sexual harassment in the workplace took any action in response.

Very few reported allegations are ever discussed outside of the company thanks to stringent non-disclosure agreements (NDAs).

The problem, labour lawyer and former executive director of the Australian Institute of Employment Rights Lisa Heap told Inq, is the severity of NDAs which gag both parties from speaking about the complaint in any detail.

“The system promotes settlements to individual complaints and non-disclosure agreements so no parties can speak about it,” she said.

KPMG, Commonwealth Bank, Telstra, Medibank, BHP and Telstra last year agreed to partially waive NDAs to allow people to submit to the Australian Human Rights Commission’s National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces, while advocacy groups are pushing for NDAs to be curtailed.

Workplace lawyer and academic Karen O’Connell said cases of people turning away from NDAs and going public had been shocking — but refreshing.

“There’s this amazing feeling of, ‘can you believe this just happened?’” she told Inq.

“But there’s still no expectation that it will happen. There is still a veil of secrecy over what happens. It is dealt with in-house, settled, or people who take the legal route drop off as they lose energy, motivation and money.”

Is it up to women?

An often-touted solution is simply to have more women on boards. But chief executive of Women on Boards Claire Braund told Inq this puts unfair pressure on women.

“I think we have to be very careful to say that’s the domain of women,” she said. “It’s not a women’s role as a director to be looking out for potential sexual harassment in the workplace.”

Companies should aim to diversify their boards across a range of skillsets — including human resources and marketing, which have more women than other sectors.

“Smart companies have worked out that if you get people on board who understand the processes, they can be quite strategic in the questions they ask and where they go looking for information,” Braund said.

Executives need to be set the example of quality culture, “enshrining principles of equity at all levels”, she said.

Is harassment a workplace health and safety issue?

Legislation around workplace sexual harassment currently frames it as a discrimination issue. It’s time that changed, sex discrimination commissioner Kate Jenkins told Inq.

The national inquiry recommended framing sexual harassment as a workplace health and safety issue, which would force organisations to proactively look at systemic risks and prevent them — instead of using a complaints-based model.

“Organisations need to track in different ways what is happening in the workplace … instead of blanket confidentiality, and not taking a complaint as evidence of a broader systemic issue,” she said.

“They need to learn what the different risks in different industries, to different employees and in different parts of the business are.”

Importantly, Jenkins felt there is momentum for change.

“We’re in a transition moment … the executives I spoke to were very keen to learn about what would work, and they were very frustrated that they felt they hadn’t been taking enough action,” she said.

“They want a good workplace culture because people perform better.”

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.