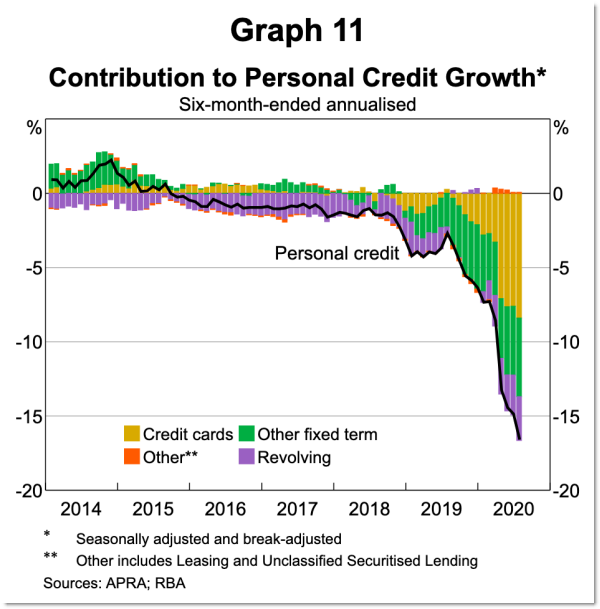

This next graph just about blew my mind. Australians are annihilating their personal debt. The fall in personal credit is unprecedented and monumental.

This is not just a bit of tweaking at the margin, it’s a serious attack on personal debt in all its forms: down 16% on an annualised basis.

My favourite part of the above chart is the huge fall in the yellow bars. Australians are finally getting on top of their credit card balances.

That’s wonderful because credit cards are voracious vampires that feed on young Australians’ futures. When official interest rates dive mortgage rates follow, but credit card interest rates remain extremely elevated. Official rates may be at 0.25% but people are still paying as much as 20% interest on cards that have points and other features. Lowering the balances on those cards will make thousands of lives brighter.

The fascinating thing about credit card balances is what might be eroding them is not as simple as a tidal wave of responsibility overcoming Australia. It is, in part, lost opportunities to max them out.

Maybe you once felt the need to put new shoes on credit, or a cool new jacket. But now the nightclubs and bars are closed. Nobody’s going to see you as you stay in your tracksuit pants and watch Netflix. This new hermit-like attitude also stops you putting your card behind the bar and shouting your friends a night of cocktails.

Marketing executive Edan O’Grady, 31, finds himself in precisely this position.

“I didn’t consciously budget in any special way during lockdown,” he told me. “I just wasn’t spending the ‘walking around’ money I normally would on coffees, lunches and after-work drinks. I ended up responsibly using the excess to pay down an old credit debt.”

O’Grady’s sudden surge of frugality was not born of desire, so much as opportunity. The effect of reduced incidental spending was so large he was able to wrestle that credit card debt into submission while also splurging on his passion for music by buying a couple of synthesisers.

“Not being able to spend money on experiences definitely helped rationalise the expensive toys,” he said.

Buy now, pay later

Visa and Mastercard must find these patterns alarming. The question is this: how much is the decline of personal credit related to the rise of Afterpay?

We all know the Afterpay story by now. The simple idea of paying off a purchase in four instalments is now a company worth $21 billion. Afterpay’s share price growth has been astronomical. If you invested in Afterpay before 2019, you’re probably reading this story from the foredeck of your yacht.

But the truth is Afterpay is on a different scale to the card companies. Afterpay claims it is responsible for $11.1 billion in sales last financial year in all the markets in which it operates: Australia, US, UK, NZ. Meanwhile, $24 billion of purchases went through credit and charge cards in the month of July in Australia alone.

That makes cards around 30 times bigger than Afterpay. It is the market leader, with Zip and Humm trailing in its wake. A transition to buy now, pay later is happening, but it’s not big enough to explain the decline in credit we’ve seen.

Public debt, private surplus

So far we’ve spoken of reduced spending opportunities and buy now, pay later, but there’s a third factor eroding private debt balances: public debt.

The more money the Australian government borrows and injects into the economy, the more Australians have the opportunity to pay down their debts. JobSeeker and JobKeeper are not just keeping the tills running at Coles and Woolworths. They’re driving debt balances down.

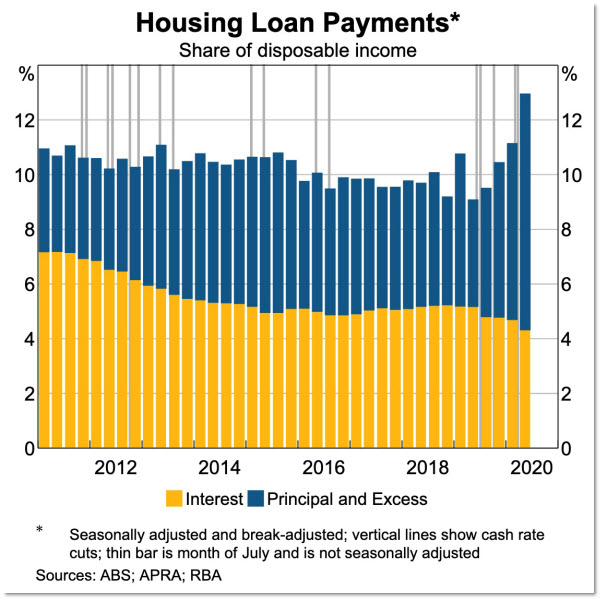

We can see a similar repayment frenzy in housing loans. As interest rates fall, Aussies are not using the spare money to buy fun products and experiences. Instead they are slamming their home loans as hard as they can, paying off the principal and making excess payments too.

It’s worth bearing this in mind as the debate drones on and on about government debt in the months and years ahead. At least some of the increase in government debt has gone neatly into helping the private sector pay down its liabilities.

For years it was private debt that seemed terrifyingly high in Australia. This rebalancing is potentially a good thing.

Good article. The other important contributor to people paying down their credit cards and mortgages was the release of some superannuation balances for people in hardship. While some may have spent this unwisely, the evidence suggests that many people used it to pay down personal debt which has helped increase the Savings rate in Australia to near record levels.

While it is certainly welcome news that people are reducing their credit card balances by significant amounts, we shouldn’t get carried away with the idea that this is a permanent change to their money management. “Why not”, you ask? Because the reduced level of outstanding balances is not being matched by a similar reduction in the amount of cards on issue, or the amount of outstanding credit limit available on them.

Once the pandemic looks like it is under control and spending options become available again, I’d bet my (less mortgaged) house on a quick and ferocious turnaround in credit card spending by the huddled masses.

Well done, Murphy. That article got me thinking. Something good has come out of the bucket of shit that is Covid-19. We can only hope that the debt addicted learn enough not to fall into the same trap once this pandemic is over.

This isn’t potentially a good thing, it is actually a good thing.

It remains to be seen whether they go back into their cards when the pandemic is brought under control, but for the moment this is unmitigated good news.

Except for the banks, who have lazily steamed along on the backs of the financially illiterate. Their profits will become much harder in future if this is a trend, and the unsustainable 15% ROIs they have been achieving will come back to something like 5-8%, which means a share market adjustment of some dimensions.

ROI, or ROE, I can’t remember.

Whilst some will likely go back to their old ways of spending on credit cards – I also think that many people will feel much more comfortable in life when having no or a small debt and will seriously consider an approach to only buy something when you have the money for it. I think it’s underestimated how much peace of mind it gives, until you actually experience the peace of mind.

I dearly wish that were true but I have seen the urge to excess overwhelm at least 3 solid, widespread social movements just in my lifetime.

History is replete with examples, from Persepolis to Trump Tower.