After more than three years of his presidency, and under the campaign scrutiny of an election less than two months away, there is no longer any surprise in describing Donald J Trump as a narcissist.

He is widely considered a self-centred and unempathetic figure who obsessively craves attention; a man who has profoundly distorted America’s responses to domestic and international challenges, and who has produced many policy failures, most notably in managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Books and essays by clinical psychiatrists and psychologists chronicle his narcissistic personality (despite the so-called “Goldwater rule”, the ethical obligation mandated by the American Psychiatric Association that clinicians not make diagnoses of public figures they had not formally examined or evaluated).

There has been some reassessment of the Goldwater rule in the nearly 50 years since it was first introduced. Ethicists and psychiatrists have asserted it is too restrictive and constrains professional clinicians from informed and ethical public commentary. But most clinicians remain reluctant to draw directly from the psychiatrists’ diagnostic bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM5), to publicly analyse Trump’s personality.

Consider, however, the following nine traits identified by DSM5 for narcissistic personality (to meet the criteria for diagnosis, five of the nine traits need to be indicated):

- Has a grandiose sense of self-importance (e.g. exaggerates achievements and talents, expects to be recognised as superior without commensurate achievements)

- Is preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty or ideal love

- Believes he or she is “special” and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high-status people (or institutions)

- Requires excessive admiration

- Has a sense of entitlement (i.e. unrealistic expectations of especially favourable treatment or automatic compliance with his or her expectations)

- Is interpersonally exploitative (i.e. takes advantage of others to achieve his or her own ends)

- Lacks empathy: is unwilling to recognise or identify with the feelings or needs of others.

- Is often envious of others or believes that others are envious of him or her

- Shows arrogant, haughty behaviours or attitudes.

How many boxes does Trump tick? Trump’s niece, clinical psychologist Dr Mary L Trump, thinks he meets all nine criteria, as she has written in her memoir about the president and her family, Too Much and Never Enough, published in July.

As a non-clinician it is, of course, inappropriate for me to attempt a diagnosis, or even make a judgement, about a personality disorder in Trump. Diagnosing psychological disorders are properly a matter for clinicians. However, I can draw upon psychoanalytic insights to illuminate his political personality — those day-to-day behavioural traits that shape the way he has conducted himself as leader of the United States and have defined his presidential performance.

The essence of Donald Trump’s political personality is actually beyond narcissism: he has what I would call an “emperor complex” — a belief that, like medieval European royalty, he is a supreme being, superior to all others, all-powerful, above the law in ruling his empire, and able to do and say anything which must be taken as valid and true.

As Emperor of All America, Trump believes he possesses the divine right of kings: he is not accountable to earthly authority (i.e. Congress) or even subject to the will of the people, whose duty is only to admire and loyally praise his tremendous power and magnificent achievements. And under the doctrine of the infallibility of kings, Trump is unimpeachable and always right. At times he seems to extend to his children this assumption of an entitlement to rule as part of an imperial royal family.

In spelling this out, let’s start with Trump’s use of his signature in an enduring ritual of his presidency: issuing fiats by signing into law legislative and executive orders and displaying the signed document for lawmakers and the assembled media in the Oval Office as a validation moment of presidential achievement.

No president has been more triumphant in holding up the signed formal record of his executive accomplishments. As he signs the page with his custom-made black Sharpie pen, he etches the big, thick lines that make up his signature, which is at once angular and condensed, yet takes up more than half a page-width of what he sees as imperial edicts. Bold and huge, his signature is clearly intended to signal his commanding authority.

Using psychoanalytic insights, how might we decipher the signature letters of “Donald J Trump” to speculate on the traits that shape and define his emperor complex?

The “D” in Donald J Trump has a number of possibilities. Despotic, defensive, deaf, devious, damaged, disloyal, disordered and dysfunctional all come to mind — as does dangerous (Mary Trump’s descriptor), which refers to all manner of damage he has done to the American system of democracy through his imperious disdain for truth in public office. He is also divisive, as in his response to the Black Lives Matter protests, associating himself with a tweet labelling peaceful protesters near the White House as “terrorists”.

But the behavioural trait he most compellingly displays is “delusional”. For Emperor Trump, the concepts of evidence and truth do not matter, and the most powerful man in the world can say anything he likes and not be accountable.

Trump has exhibited delusional behaviour many times during his term in office, starting with his description of the crowd at his 2017 inauguration as the biggest inauguration crowd ever– a description the White House sought to bolster through manipulated photographic images.

This was Trump’s coronation moment, the occasion of his enthronement, and he cannot bear to have his consecration diminished by comparisons with his rivals — those he regards as inferior beings — even if the rivalry exists only in his imagination. For Trump to accept that his predecessor, Barack Obama, had a larger crowd at his inauguration would be internally wounding and demeaning, and he is driven to avoid it with delusions of exaggerated superiority and self-importance.

This early delusional flourish was merely a hint of what was to come. Since then Trump has come to sharpen his obliteration of his perceived enemies — and those who deny his claim to greatness — with his frequent use of the word “fake”. This has become the epithet of choice for Emperor Trump: not merely is someone who opposes him wrong or even despicable, they are illegitimate and can be banished from his mind.

Obama has been a special target for Trump, going back to his assertions during Obama’s first term that America’s first Black president was born in Kenya rather than Hawaii, and hence was not constitutionally eligible to serve in the White House — merely a “pretender” to the throne. His delusions about Obama were not merely a political claim that his predecessor was misguided or ineffectual, or took the country in the wrong direction, but that he occupied his office illegitimately.

This is the ultimate put down by Trump — not merely the political disparagement of an imagined rival but the denial and destruction of his legitimacy. With no credible evidence whatsoever for his “birther” claim, Trump destroyed in his own mind the authority of the man who stood in the place he coveted.

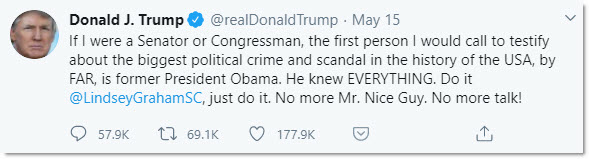

It wasn’t enough, however, and Trump’s obsession with Obama has continued, perhaps intensified by Obama’s mocking of Trump at the White House correspondents dinner in April 2011. Humiliated by the audience laughing at him, Trump has never let go, tweeting in May this year that Obama was responsible for “the biggest political crime and scandal in the history of the USA, by FAR … [a crime that] makes Watergate look small time”.

However, at a subsequent press conference when pressed by journalists to explain this baseless claim, Trump replied: “You know what the crime is. The crime is very obvious to everybody. All you have to do is read the newspapers…” (He continued his “denial of legitimacy” ploy with comments in August about the Democratic candidate for vice-president, Kamala Harris, who he falsely claimed was “ineligible to serve” if she was elected in November because she was born in the US to immigrant parents.)

Delusions of imperial grandeur are also a feature of Trump’s personality. He boasts that everything he does is amazing — the biggest, the best, the grandest and most beautiful. This became apparent in 1982 with the completion in New York of the extraordinary Trump Tower, the family apartments which are decorated in a gaudy mix of the opulent style of the French emperors’ palace of Versailles, the columned temples of ancient Greece and the grand palaces of Russia — a style which has been disparaged as “haute Miami Vice elegance”.

These gilded private rooms, with fixtures in 24-carat gold plate, are an expression of Trump’s inner need to feel regal — even King Midas-like. On its website, the Trump organisation says of the building that it “stands as a world famous testament of Mr Trump’s grand vision and ability to achieve tremendous success with everything he touches”.

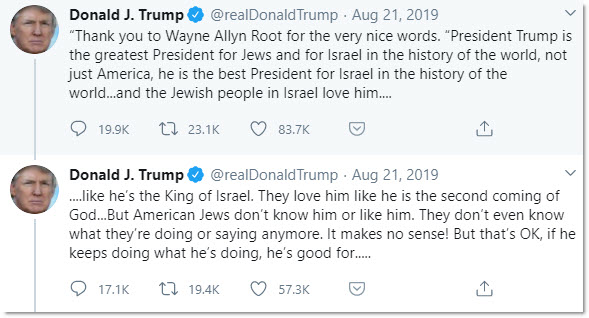

The delusional trait is also found in Trump’s Twitter communications, both in his own words or those of others who say what he really thinks and believes. Last year he quoted a conservative radio host who called him “the greatest President for Jews and for Israel in the history of the world, not just America, he is the best President for Israel in the history of the world … and the Jewish people in Israel love him like he is the King of Israel. Like he is the second coming of God.”

As we know, Emperor Trump tweets the messages of others that reflect his inner beliefs. His delusions are repetitive and obvious and have a common element: he is a tremendous president, and the greatest, the most perfect leader of his subjects.

This is a recurring claim that he makes, as he did in July 2019: “I am the least racist person there is anywhere in the world.” It was apparent again when, in disputing the impeachable character of his so-called quid pro quo phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, he described the call as “perfect”.

Consistent with this delusion, when things go well Trump takes the credit; when they go badly, it’s always someone else’s fault. This was clear when he made the grandiose promise of completing the wall between Mexico and the US. When it was not completed, he blamed the political establishment, the news media — everyone but himself.

More recently, in early March this year, Trump minimised the seriousness of the coronavirus pandemic for the US — blaming the “fake news” media for spreading panic — as if accepting the enormity of this threat would somehow diminish his standing of Imperial Majesty.

As appropriate as “delusional” is to describe a key Trump trait, it has to be acknowledged that it is accompanied by high-level political acumen. On the flip side of his delusions is an unerring capacity to pick the weaknesses of his political rivals, perhaps through unconscious projection of his inner vulnerabilities. It is as if his delusions about his own inflated capabilities (founded as they are in unconscious defences against a profound inner sense of inferiority) enable him to crystallise the personality flaws of his opponents — to endow them with the personality traits he denies in himself.

The second letter of Trump’s royal signature — “O” — is also instructive: obscene, outlaw, outlandish, obsessive and oppositional are in the frame, but the signature “O” word that best fits is “omnipotent”, and it’s a particular expression of his delusional and authoritarian behaviour.

Trump always sees himself as the best, the greatest, the smartest — but particularly the most powerful. Even from the outset of his presidential candidacy, he articulated his grandiose sense of himself. Accepting the Republican nomination in July 2016, he declared: “I am your voice. I will be a champion, your champion. Nobody knows the system better than me, which is why I alone can fix it.”

It has also come out in his periodic declarations of his monarch-like authority: “When somebody is president of the United States, your authority is total.” Trump said this in an angry tirade at a press conference on April 13 in response to criticism of his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. His seeming omnipotent authoritarianism is not the expression of a developed philosophy of governing, but a reflection of his self-centred preoccupation with ruling — of being in total control of his empire and its subjects.

The key letter for Donald Trump is “N” for “narcissist”. This is the umbrella letter for his core political personality, and it is no exaggeration to say that all the other behavioural features flow from this. He has a hyper-narcissistic personality, and whatever he does in office is really all about him.

All successful leaders have a healthy degree of self-regard — and a certain measure of associated paranoia; qualities necessary for political action and leadership survival. But when they become excessive and overpowering they can lead to debilitating and dysfunctional ways of acting politically.

More importantly, when these traits include a mix of other antisocial personality traits — what clinicians call “malignant narcissism” — sociopathic behaviour can emerge.

There are several features of Trump’s narcissistic and paranoid personality that shape a consistent pattern in his political behaviour. The central features are a distinctive marketing acumen and political drive that is accompanied by paranoia and destructive tendencies — anger, rage, envy and resentment — which suggests an inner dynamic involving overweening ambition defending against (that is, compensating for) low self-esteem.

The psychoanalytic literature on narcissistic personality is extensive and important to understanding Trump’s political personality, his emperor complex. At the core of modern theories are the concepts of the “narcissistic self”, in particular the “grandiose self” — the unconscious structure holding omnipotent and exhibitionistic wishes regulating behaviour and self-esteem.

The grandiose self, whose central mechanism may be stated as “I am perfect”, is a normal part of the child’s sense of itself. Under optimal conditions the exhibitionism and grandiosity of the child is gradually tamed, gives way to more realistic functioning, and becomes an important element in adult self-esteem. However, if the child’s development is disrupted by narcissistic trauma, whether real or imagined, it may persist unaltered in the adult formation of exaggerated ambition.

It is worth noting here that Trump has described his father Fred as demanding, difficult and driven, Indeed, from multiple biographical accounts of Trump’s early life, including most recently Mary Trump’s book, his father seems even more extreme — a sociopathic, relentlessly dominating, bullying and emotionally inaccessible parent. Trump’s emotional development was seemingly snap-frozen in early childhood when he appeared defensively combative, aggressively competitive and dominating. For the young Donald, losing meant inner obliteration.

In short, it seems the child persona has persisted into his adult behaviour. As he told a recent biographer: “When I look at myself in the first grade and look at myself now, I’m basically the same.”

In his classic study published more than 40 years ago, US psychoanalyst Otto F Kernberg MD identified a number of distinctive characteristics of the narcissistic personality. This type, he wrote, typically presents with “excessive self-absorption hand in hand with … various combinations of intense ambitiousness, grandiose fantasies, feelings of inferiority, and over-dependence on external admiration and acclaim, they suffer from chronic feelings of boredom and emptiness, [and] are constantly searching for gratification of strivings for brilliance [and] power”.

Other predominant characteristics “include a lack of capacity for empathetic understanding of others … conscious or unconscious exploitativeness and ruthlessness toward others and, particularly, the presence of chronic intense envy and defences against such envy”.

Trump’s behavior has been exemplified by many of these problematic features, the first of which is a tendency towards intense envy and resentment of those who, he believes, have entitlements greater than his own.

This is linked, second, to an ambivalent attitude towards elites and people in authority — for example, promising to “drain the swamp” at the same time as aspiring to rule over the swamp. At other times this appears as a tendency to enviously abuse and tear down to his level anyone within his orbit he perceives as occupying a superior position and casting a shadow over his throne.

Third, he shows in his political behaviour an obsessive concern to assert that he — above all others — is in control. And fourth, he shows a tendency towards paranoid fantasies, a hyper-sensitivity to criticism, where he sees friend and foe alike as attacking or undermining him.

Trump’s inner sense is that he is never wrong. If someone questions, even for a moment, his claim to unparalleled greatness, they are met with withering and unrelenting retaliation.

Associated with these features is a high level of rage at a political world he struggles to bend to his will. It’s a world that he vilifies in his tweets, a social media monologue that, like its author, is occasionally perceptive but mostly destructive and sometimes paranoid. These are features of the emperor complex that drove Trump to seek and attain the presidency. But they are also qualities of a flawed personality that make his presidential reign highly problematic and unsustainable.

At other times, when his sense of entitlement is breached — the demands of his grandiose self-image betrayed — he responds with retaliatory rage and retribution. This becomes clear in relation to his political associates — the imperial court — with whom he makes common cause at periods in his political rise.

A strong common element here is that his brittle shell will not allow any scintilla of criticism, and any deviation from wholehearted support by courtiers, staff and allies is responded to with a flight to rage and vindictiveness.

Trump’s sensitivities are evident in his experiences with successive White House chiefs of staff. One by one they have fallen foul of Emperor Trump’s need to be self-sufficient in his political decision-making. Trump sees his advisers as either loyalists or rivals, and they are most vulnerable to his impulsive and bullying instinct when they were best doing their jobs: telling the emperor what he does not want to hear. Successive close advisers have lamented their inability to make Trump take advice.

The point is less that Trump won’t take advice, but that he can’t take advice: to take the advice of a subordinate is humiliating and he can’t do it — unless and until he can convince himself that it was his advice in the first place, that he was the author of this masterstroke of strategy or politics that would be universally applauded as “brilliant” and “amazing”.

Trump is profoundly insecure and feels threatened when prospective staff have professional experience, standing and seniority that rivals his sense of superiority. At the start of his presidential term he dealt with that by appointing courtiers and devotees — inexperienced juniors — to his staff.

His campaign press secretary was Hope Hicks, a 26-year-old former model he later appoint to the role of White House director of strategic communications, despite the fact that she had no experience in government. This is less a case of Trump appointing a loyal associate than of ensuring the power relationship between president and advisers is uncomplicated by appointing seasoned professionals who might provide frank, fearless and independent advice.

He has also drawn upon the imperial entitlement of his imagined royal family to appoint his daughter Ivanka, and son-in-law Jared Kushner, to senior adviser roles, although they had negligible skills for their positions.

Trump’s insecurity becomes more obvious when subordinates have a standing or get media and public attention he believes is rightfully his. In the early days of his presidency, the reported power behind the throne was Trump’s campaign chief executive and chief White House strategist, Steve Bannon, who developed a high public profile and received intense media attention and accolades from commentators about his campaigning success.

Trump regarded this attention as demeaning of his own pre-eminent imperial position and went out of his way to disparage Bannon, putting him down in a way that allowed the proper hierarchy of greatness to be restored in his favour.

Eventually Trump could not endure Bannon’s prominence and he fired him in August 2017, after which he belittled Bannon’s role and denied his influence. In fact, he trashed Bannon as merely “a guy who works for me” and said “sloppy Steve” Bannon “cried when he got fired and begged for his job”.

Eighteen months after he was dismissed, and well before he was arrested on fraud charges, Bannon was able to work his way back into the emperor’s favours, in part by publicly calling him “a great leader as a president” and a “great campaigner” — whereupon Trump felt able to say that Bannon was “one of my best pupils” and “still a giant Trump fan”. Notice that even in his renewed praise he keeps himself as the central object of admiration.

Trump has fallen out with other close court advisers — none of whom has lasted for more than 18 months — including chiefs of staff Reince Priebus and General John Kelly, and national security adviser John Bolton. Most recently his health expert on the coronavirus, Dr Anthony Fauci, incurred Trump’s displeasure, primarily because the president cannot abide anything less than devoted cheerleading from his courtiers.

When a subordinate’s advice is later shown to be well based, and Trump appears to have been publicly at odds with it, he reacts severely, as was the case with Fauci. This happened when, in a CNN interview earlier this year, Fauci said Trump had “pushed back” against his early advice about mandating social distancing to combat the spread of the coronavirus — an initiative, Fauci said, that had it not been delayed “would have saved lives”.

This was too much for Trump, and he retweeted a conservative call for Fauci to be fired. In effect, he was projecting his inner wish for retribution at the suggestion that his imperial rule was flawed. It is only when Fauci walked back from the meaning of his comments and praised the president for his handling of the pandemic response that Trump disavowed banishing him.

Others have not been so lucky. Months after Trump’s impeachment, for example, he was still paying out by firing those government officials who honoured their ethical duties in relation to the Ukrainian quid pro quo. Trump cannot ever accept the betrayal he feels about their conduct: in his mind, their loyalty is not to the republic or to their office, but unquestionably to him as emperor, and any deviation is met with aggressive disparagement and ultimately (in his mind) obliteration — by firing them.

Incidentally, there are interesting echoes here of Trump’s TV program, The Apprentice, where his signature statement was “you’re fired!” In the Middle Ages it would have been “off with his head!”

A central feature of Trump’s personality is his pronounced lack of empathy. At his press briefings, when he has conjured the numbers of COVID-19 cases or deaths, he has expressed little sympathy or empathetic understanding for those who have lost family or loved ones.

Back in March, in one of the more insensitive expressions of this trait, he conceded that he wanted to keep a cruise ship in limbo off the California coast rather than allowing it to dock because he wanted to keep the reported number of coronavirus cases artificially low. “I like the numbers being where they are,” Trump said. “I don’t need to have the numbers double because of one ship … If they want to take them off, they’ll take them off. But if that happens, all of a sudden your 240 [cases] is obviously going to be a much higher number, and probably the 11 [deaths] will be a higher number too.”

More recently, Trump seems to have given up on accepting responsibility for managing the pandemic, using distractions about employment numbers and the economy and law and order to divert attention from mounting infection rates and deaths. He has also urged reduced testing for the virus in the deluded belief that less testing means fewer cases.

The flip side of Trump’s narcissistic self-regard is paranoia, which manifests as a kind of persecutory anxiety: nobody is spared, he sees friend and foe alike as attacking him, and his emblematic expression is one of distrust in others. “I don’t trust anybody but myself,” he seems to be saying. “Everyone else is trying to undermine me and my claim to greatness.”

As we’ve seen earlier, a feature of his political persona is his denigration of his political colleagues as a way of raising himself up in his own estimation. One expression of this is the extensive list of disparaging nicknames he gives to both his political opponents and his erstwhile supporters.

Competitive rivalries between politicians in leadership positions are normal and inevitable. But in Emperor Trump’s case this takes a somewhat relentless and extreme form: he systematically belittles and demeans the activities and efforts of his party colleagues, as if only his actions are worthy and good. This destructive envy spreads to anyone he feels stands taller than him and, hence, one by one his colleagues — whether supporters or rivals — are characterised as “crazy” or “crooked” while his activities are extolled as “tremendous” and “perfect”.

Trump has a characteristic way of belittling real and imagined rivals who even momentarily challenge his elevated regal authority. They are variously “crazy”, “sleepy”, “sloppy”, or “lying”. Going back to the Republican presidential nomination process in 2015 and 2016, his rivals were “low energy Jeb” Bush, “little Marco” Rubio, and “lyin’ Ted” Cruz.

Four years later, as the Democratic party nomination process got under way, he targeted “sleepy, creepy Joe” Biden, “crazy Bernie” Sanders, “fake Pocahontas” Elizabeth Warren and, later in the process, “mini-Mike” Bloomberg.

Trump’s denigration of rivals or would-be rivals reveals his inner self: anyone who emerges to challenge his pre-eminent position of entitlement is a threat to his sense of himself and has to be cut down to size. His Democrat Congressional detractors are put down in the same way (“crazy Nancy” Pelosi, “little Adam” Schiff, “cryin’ Chuck” Schumer), as are his supposed tormentors in the media (“crazy Jim” Acosta, “sloppy Carl” Bernstein, “crooked H Flunkie” Maggie Haberman, and “little wise guy” George Stephanopoulos), among many others.

It’s no surprise, incidentally, that Trump hates the media, since journalists are most frequently the source of the critical reporting and commentary that he finds demeaning and threatening to his grandiose inner sense of self. It’s why he brands anything less than unqualified admiration, if not idolatry, as “fake news”.

Trump’s deadliest venom in recent times has been directed at his former opponent in the race for the White House, Hillary “lock her up!” Clinton. Trump has never accepted that while he won the presidential election through his majority of delegates in the Electoral College, Clinton nationally polled 2.8 million more votes than he did. Unable to be gracious in victory, he still has to belittle her as “crooked Hillary”, lest anyone think she might have been more popular than him.

It is worth considering who Trump likes and admires. Mostly it’s other national leaders — all of them autocrats — with whom he can appear on an elevated world stage. Foremost in his relationships has been his enduring admiration for Russia’s modern-day tsar, President Vladimir Putin. In new evidence reported by CNN at the end of June, veteran journalist Carl Bernstein cites US national security officials with authorised access to Trump’s classified telephone conversations with Putin as dismayed by the pandering approach he took to the Russian leader — in sharp contrast to the abusive tone he adopted in speaking to democratic allies in German Chancellor Angela Merkel and former British PM Theresa May.

Trump’s clear preference for authoritarian bullies has been obvious in his relationships with rulers such as Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte, Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, and more recently Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro.

Trump’s relationship with China’s authoritarian president Xi Jinping has been admittedly on-again, off-again, and he has been ambivalent about North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un. At some points, Trump liked Kim, perhaps because when they met in the demilitarized zone between South and North Korea in June 2019, Kim appeared deferential and compliant in his body language. This was appealing to Trump because he could satisfy his grandiose sense of himself as the dominant party strutting the world stage. Of course, lest anyone think Kim eventually got the better of him through his diplomatic game-playing, Trump looked to cut Kim down to size, once again describing him as “Little Rocket Man.”

There are any number of “A” letters that a decipher of Emperor Trump’s signature suggest: angry, ambitious, amoral, anti-democratic, adolescent, abusive, antagonistic, aggressive and autocratic commend themselves, as does attention-seeking, which characterises Trump’s pursuit of the presidential throne in the first place. This was not about Trump seeking to realise a developed vision of leading and governing in the national interest. This was about leveraging the foremost position in the country to attract attention to himself, to become more powerful and more famous than anyone.

The “A” word that fits best, however, is “arrogant” — a belief that he is better than others and knows more than anybody, even when the reality is that he doesn’t have a clue.

Trump’s arrogance is a defence against his profound inner sense of inferiority. He has claimed countless times while in office that he had extraordinary special knowledge about politics and public policy. Typically he has expressed this as: “Nobody knows more about [x] than I do.” He has claimed he knows more “than anyone on earth” about defence, nuclear weapons, Islamic State (IS), the courts, technology, the environment, renewables, money, taxes, trade, banks, healthcare, infrastructure, construction and campaign finance among an extensive list. It comes as no surprise that he has described himself as “a very stable genius”.

He invoked his claim to “genius’ again in March on a tour of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, when he felt obliged to overcome his lack of any real understanding of the laboratory experiments into infectious diseases that CDC medical researchers are distinguished for. So he bragged to the media accompanying him about his “great super genius” uncle, an MIT medical engineering professor, to assert that he himself had a natural ability as a medical doctor and researcher: “I like this stuff. I really get it. People are surprised that I understand it … Every one of these doctors said: ‘How do you know so much about this?’ Maybe I have a natural ability, maybe I should have done [become a medical researcher] instead of running for president. But you know what? What they’ve done is really incredible. I understand that whole world, I love that world. I really do. I love that world.”

Trump cannot even for a moment accept that he has — like the rest of us — merely a rudimentary understanding of complex medical science, so he has to exaggerate — in this case by invoking his connection to his highly accomplished uncle — to momentarily project into the minds of the media audience the thought that he could have been a “great super genius” too.

There have been other occasions when Trump has looked to present himself as the guy who could cure coronavirus, notably with drugs such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. When his medical advisers warned that these were untested and potentially hazardous he pushed back: “I disagree. I feel good about it … I’m a smart guy. I’ve been right a lot.”

On April 23, Trump continued his “super genius” delusion by suggesting at his daily press briefing that a combination of UV light-zapping and disinfectant injected into the lungs could be a possible cure for coronavirus-infected patients. As CNN reported, when a journalist asked “why he was touting rumoured cures and not medically proven science”, the president reacted angrily, accusing the reporter of pushing fake news.

The next day, “Lysol” Don sought to further deflect the outrage from medical scientists by claiming he was only being “sarcastic”. Since then he has claimed that he had started taking hydroxychloroquine himself. Consistent with his relentless disposition to never let go, this seems like an attempt to buttress his first claim and reassert his authority after being widely ridiculed.

The letter “L” presents a number of possible interpretations — lewd, liar, licentious are just a few — but “lawless” is appealing, aligning as it does with Trump’s sense that he is above the law, that the law is whatever he says it is. The basis of the impeachment proceedings started in the House of Representatives were that Trump had abused the power of his office and unlawfully obstructed the Congress in breach of the constitution. As we know, while the House voted to impeach, he was acquitted by the Senate on both counts.

The point to make about Trump’s lawlessness is not that he recklessly flouts the law or wilfully breaks it, but that as a reigning emperor he doesn’t believe he is bound by the law. Like Richard Nixon before him, who famously said that “when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal”, Emperor Trump has the inner conviction that his tremendously important position means he is above the law. As he said at a conservative student conference in July 2019: “Under Article II [of the constitution], I have the right to do whatever I want as president.” In effect, he believes he has an unimpeachable entitlement to rule.

Trump repeated the point in his media briefing on April 13 when he claimed “total authority” over the states in relation to COVID-19 lockdowns. This is less an expression by Trump of a developed argument about the limits or otherwise of presidential powers than a reflection of his inner sense of his dominant, unquestioned royal authority.

Indeed, his April 17 tweet inciting his supporters to protest against social distancing lockdowns by state governors — “Liberate Michigan”, “Liberate Minnesota”, “Liberate Virginia” — provides a hint of his inner state of mind in asserting his legitimate dominance, and that the law is whatever he says it is.

The second “D” offers a number of deciphering possibilities: devious, disordered, disturbed, destructive, deranged, demented, dissolute, distrustful or despotic; or perhaps — given its second occurrence in the signature — double-down, which is tempting given that when challenged on something he says that is shown to be false, Trump simply doubles-down and says the criticism of him is just “fake news”. Through his imperial powers, the truth is whatever he says it is.

But the “D” that looks closest is “distrustful”. This quality of never really trusting anyone was foreshadowed early in Trump’s term by his treatment of FBI director James Comey in a meeting at the White House on January 27, 2017, shortly after Trump’s inauguration. At the one-on-one dinner — which took place amid the FBI probe into Russian meddling in the 2016 election — the new president improperly sought to extract a commitment of personal loyalty from Comey, superseding the FBI director’s oath of allegiance to the constitution and the duties of his high office.

Having failed to secure such a pledge of fealty from Comey, Trump could never trust him, later calling him “an untruthful slime ball” and a “proven LEAKER and LIAR”, and eventually firing him in May 2017. As Comey later wrote in his memoir, Trump’s behaviour in office was “unethical and untethered to truth” and — in respect of his demand for personal loyalty as the basis of any trust and working relationship — like that of a Mafia boss.

“J” is a central letter in the Trump signature, and it has a singular character, perhaps aligned with jealous and judgemental, both of which traits Trump frequently exhibits. And then there is jingoistic, an extreme nationalism in framing US foreign policy, which conveniently matches Trump’s inner need to dominate, even globally.

With Trump, even the political campaigning objective of “Make America Great Again” takes on an aggressive quality as he runs down allies and enemies alike to elevate the US — but particularly himself — in the global leadership stakes. (It’s tempting to think of “America first” as really “me first”, because in his mind Trump and America are one and the same.)

Jingoistic he certainly is, but the most compelling “J” is “juvenile”, a Trump trait abundantly in evidence through his immature, even childish, behaviour. This was on show at a NATO meeting in Brussels in May 2017 in what came to be known as “the shove”. Walking with other leaders to a planned photograph at NATO headquarters, Trump momentarily found himself positioned behind a group of presidents and prime ministers slowly shuffling toward the photo-op point. Like a child in a playgroup, Trump abruptly shoves out of the way the NATO colleague inadvertently blocking his path — who happens to be the leader of tiny Montenegro, Prime Minister Duško Marković.

Trump’s intent is to assert his entitlement to be at the front of the group (not unreasonable in the global scheme of things, of course), especially ahead of this Balkan nation state, which has a population of a mere 620,000. His abrupt manoeuvre successful, Trump self-consciously flaps his suit coat as if to say: “Outta my way. I’m the king of this sandpit!”

The “T” is a big deal in the Trump signature: along with the opening “D” and the final “P”, it is the tallest letter on the signature page, over-reaching the others like Trump Tower on the Manhattan skyline. Treasonous and treacherous are possible, and transactional appeals too. Certainly Trump has been quintessentially transactional in his presidential behaviour, as in the Ukrainian quid pro quo, where his presidential negotiations and positioning were clearly motivated by the prospect of personal political advantage rather than advancing US national interests.

This has been a consistent approach, well documented over time, harking back to his early business dealings as a New York property developer where he made political donations to elected city officials, Democrat and Republican, to create a political obligation that could be called in to his financial advantage when required.

Transactional though Trump certainly is, the “T” word that best expresses a core personality trait is “tyrannical”. That is not to say Trump is a tyrant per se, although his propensity to fire those administration officials who cross him comes close to tyrannical behaviour. Indeed, there is a litany of officials Trump has fired because they have been doing their job in respect of Congressional and intelligence community oversight, but in ways that Trump perceives as offensive to his sense of himself as perfect.

Trump’s tyrannical trait reflects the fact that he has an inner wish — a compulsion — to dominate, to exercise unfettered power and control absolutely, to never be constrained by laws or principles or ethics or counter-balancing institutional authority. Like so many of Emperor Trump’s behavioural political instincts, it derives from his inner conviction that he is unique, he is a tremendously majestic and powerful person, one without peer or blemish on the national and global stage.

There are several “R” words that fit the bill — reckless, rabid, remorseless, rivalrous and raging — but the closest reading is “resentful”. Like Nixon, Trump is a serial collector of resentments and at times his political outlook is dominated by extreme suspicion and distrust, hostility, and a pervasive preoccupation with enemies, real or imagined. He stores up his resentments and takes every opportunity to get even, usually by firing courtiers who offend his sense of superiority.

Trump has an extremely low threshold of tolerance for anyone who doesn’t vow fealty to his imperial sense of himself and so he has forced out multiple senior White House counsellors, advisers and special assistants, national security advisers, the US deputy attorney-general, the secretary of state, the FBI director and deputy director, Justice Department officials, the secretary of Health and Human Services, as well as competent senior officials in many other departments.

This is especially true for a raft of independent inspectors-general, officials in oversight roles in the US administration who have incurred Trump’s wrath just for doing their jobs with integrity. In fact the turnover rate in the Trump administration has been record-setting. No doubt some staff have left of their own volition, but a number of reports have pointed to a toxic culture within the Trump administration — the consequence of capricious expression of presidential resentments — as the cause.

It is tempting to suggest this is not the promised “draining the swamp” as Trump might have it, but the trashing of vital administrative capability on the whim of a deluded and resentful emperor. Trump’s resentful trait was further in evidence recently when — hypersensitive to any hint of criticism about his “perfect” performance on the COVID-19 outbreak — he ordered a cut in US funding to the World Health Organization (WHO). Since then he has taken action to withdraw the US from WHO altogether.

There are myriad Trump traits associated with the letter “U”, beginning as it does numerous “un” words. These are the contra versions of the positive qualities so conspicuously absent in Emperor Trump: unprepared, unruly, unethical, unsympathetic, untethered, unstable, unforgiving, unthinking, unprincipled, unscrupulous, unreflective, and unrepentant. Unempathetic also has a certain appeal.

Unforgiving is relevant too, capturing that vindictive trait that he can never let go of a slight and has to pay out on the source. This was how he behaved toward his Republican rival, the late Arizona senator John McCain, the Vietnam War pilot and prisoner of war he periodically disparaged in a 20-year feud because McCain stood in the uniquely elevated position that Trump knew he could never reach, much less surpass — that of American war hero.

Perhaps feeling humiliated as the former military academy student who never served during the Vietnam War (granted multiple deferments because of his college status and later exemption because of supposed bone spurs in his feet), the best Trump can do in his unforgiving way is mock McCain as a captive of the North Vietnamese: “He’s not a war hero,” he said in a July 2015 interview. “I like people who weren’t captured.”

Trump’s evident contempt for US military sacrifice was reportedly on display during a presidential visit to France in 2018. According to The Atlantic, Trump cancelled a visit to war graves at the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris because (as he allegedly said to senior staff members) the American soldiers who had fought and died in World War I were “losers” and “suckers” for getting killed.

This is Trump rationalising to himself the “smartness” of his own unwillingness to serve in Vietnam. Any reasonable comparison, even in his own mind, between his avoidance of military service and the bravery of those combat soldiers who put themselves in harm’s way would be deeply humiliating for him, so to maintain his inner sense of superiority he has to disparage their sacrifice as meaningless or stupid.

“Unhinged” is the signature word of choice here, however, referring as it does to the emotionally unbalanced way in which Trump has often behaved, especially in relation to the present COVID-19 pandemic. When the coronavirus outbreak first appeared, Trump went on the attack, accusing the Democrats of fostering a new hoax.

“They tried the impeachment hoax,” he said on February 28. “This is their new hoax.” A little over two weeks later, on March 17, Trump was insisting he knew before anyone how serious COVID-19 was: “I’ve always known this is real — this is a pandemic. I felt it was a pandemic long before it was called a pandemic.”

Trump has been consistently unhinged in his responses to the health crisis. How else to explain his unwillingness to adopt a disciplined and focused leadership of the US response? Since the outbreak, he has relentlessly advanced and backtracked, uneasily trying to juggle the demands of evidence-based, scientific health advice in the best interests of the American people with his inner imperative to give priority to his own political interests through a booming and unconstrained economy.

Trump has been unfit and mentally unprepared to articulate a coherent strategy through this crisis — a pathway that Americans can heed and have confidence in, and the rest of the Western world can respect and follow. Through his unhinged leadership, Trump has untethered the US from its near century-long great-power role on the world stage.

The letter “M” offers interesting decoding possibilities such as manipulative, megalomaniacal, mad and mendacious. The one that gets it, though, is “misogynist”. This is not normally a term describing a narcissistic personality trait, but in Trump’s case it is important because it provides yet another revealing expression of his hyper-sensitivity to slight.

Trump commonly sees women as inferior, dependent, and even — in his entitled way — as his sexual playthings. The latter emerged in 2005 in a hot-mic conversation recorded on a bus when travelling to film an episode of the TV program Access Hollywood. Trump boastfully related his sexual exploits with women made possible by his status as a TV star: “When you’re a star, they let you do it. Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything.”

Women are a special challenge for Trump. Defining them in his mind as inherently dependent, lesser beings, he cannot allow any turning of the tables when he encounters smart, highly educated and assertive women –as he did in the Republican presidential debate in August 2015 when Fox News journalist and debate moderator Megyn Kelly got the better of him. In a question to Trump, Kelly called him out on his record of insulting and disparaging women.

“You’ve called women you don’t like fat pigs, dogs, slobs and disgusting animals,” Kelly said. “Does that sound to you like the temperament of a man we should elect as president?”

Skewered by the question, Trump was doubly offended because he has been taken down by a woman — one he later disparaged in a repulsive tantrum as “crazy Megyn” Kelly, who had “blood coming out of her wherever”.

Trump is also consumed with resentment and envy when he feels that his entitlement is breached by others undeserving of his celebrity position, as he did in December last year when teenage Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg was chosen as Time magazine’s Person of the Year for 2019. Even though Trump had been the Time Person of the Year in 2016, he evidently felt humiliated by her elevation over him, depriving him of an opportunity to equal his rival, Barack Obama, who had been named Time Person of the Year twice.

One of 10 short-listed nominees with Thunberg in 2019, Trump’s humiliation was perhaps deeper because Thunberg was only 16, and he lashed out at her in a way that was designed to further cut her down to size. “She beat me out on Time magazine,” he commented testily, after tweeting his ire about her being named for the award: “So ridiculous. Greta must work on her Anger Management problem, then go to a good old-fashioned movie with a friend. Chill Greta, Chill!”

Here again is an expression of Trump’s preoccupations revealing his inflated but fragile sense of self — a sitting US president feeling diminished by the celebrity of a teenage girl he momentarily regards as a rival for the high accolades to which he feels entitled.

So to the last imposing letter in the Donald J Trump signature: the letter “P” and the distinctive final signature flourish of a plutocratic, petty, paranoid, predatory, petulant, punishing and psychopathic personality. Fitting as these descriptions might be, the “P” word that best describes Trump is “Putinesque”. Like the word misogynist, Putinesque is not a psychological term but it expresses a behavioural trait of Emperor Trump in an instructive way.

Trump reveres Putin because the kleptocratic Russian president has the attributes that Trump aspires to for himself: unconstrained imperial power, seemingly unlimited terms of office, vast wealth, and no political rivals to contend with — primarily because Putin “locks them up”, or worse. Such is Trump’s infatuation with Putin that he cannot even bring himself to denounce the covert bounties paid by Putin’s Russia to Taliban-linked militants to kill American combat troops in Afghanistan.

Putin is arguably the most autocratically powerful person in the world — an achievement shared perhaps only with China’s President-for-life, Xi Jinping — and his personal wealth is estimated to be somewhere between US$70 billion and US$200 billion. By contrast, Trump’s fortune is thought to be just US$2.5 billion.

For Trump, Putin’s unchallenged position of authority represents the ideal of his own grandiose ambition to be the most powerful, the wealthiest and tremendously superior person on the planet. (It didn’t hurt either that — as Trump reported in May 2019 — Putin wrote him “beautiful letters”.)

Putin was also recently successful in rewriting the Russian constitution to allow him to serve two further six-year terms. Is it really outside the bounds of possibility that, if Trump looked to be defeated at the presidential poll in November, he could assert that the COVID-19 crisis “demanded” he intervene to delay the election (to a politically more advantageous date), despite the constitutional and statutory provisions denying such a power?

Trump has already started to manipulate the election with his assault on the capability of the US Postal Service to manage mail voting for the election. The most concerning possibility would be for Trump to invoke the National Emergencies Act 1976 in the lead-up to the election to disrupt elements of the vote.

And if he is defeated in the election, might he move to disallow “invalid” votes in the Electoral College to keep himself on the throne? Or would he unleash armed and lawless protesters, as he encouraged those who menacingly entered Michigan’s state parliament in late April, describing them as “very good people”?

Certainly, such manoeuvres would be entirely consistent with, if not exemplify, some of the core traits of the emperor complex we have now deciphered in Donald J Trump: delusional, omnipotent, narcissistic, arrogant, lawless and distrustful. Juvenile. Tyrannical, resentful, unhinged, misogynist and, perhaps most worrying of all, Putinesque.

It has always bothered me when media outlets ask Trump if he’ll accept the electrion result – they’re helping normalise the notion that lawbreaking is an acceptable course of action.

I believe that when asked about it, Biden said he had great faith that the Secret Service would be able to remove an intruder from the White House.

But the more it gets talked about, the more people will regard it as a realistic option, and the less they’ll complain if he tries it on.

Undecided and centrist voters are being pulverised, which can only mean US politics will become more partisan (hard to imagine but always possible).

For the whole planet’s sake I hope they can pull themselves out of the death spiral they’re in.

Most Americans do hold the Constitution to be a cornerstone of their country and being. I mightn’t be watching broadly enough what is happening in America, but what I am seeing is major concerns for their constitution and democracy at the moment. I don’t think seeing Trump answer (or not answer) a question indicating that he may trample America’s constitution and democratic values is going to normalise it for the average American. For his most enthusiastic supporters, perhaps, but they would have been there with him if he just did it on election night without any notice.

“But the more it gets talked about, the more people will regard it as a realistic option, and the less they’ll complain if he tries it on.”

Alternatively, if he was to do it without any pre-announcement, they may just consider it too late to do anything about it.

Well done Michael, you have unearthed one of the driving forces behind what it takes to create a “trump”, this is what this article should really be about considering the fanfare the editor gave .

Normalising the concept of lawbreaking is endemic in media. It also normalises behaviour and attitudes that are destructive coercive,unethical or simply to gain market share.

Aldous Huxley touched on mass marketing strategies that indulged the population with self interest and weakened community interest.

Trump is the latest product of psychoanalysis ,weaning the population into cost effectiveness for the greater corporate world.

Channeling people away from tasks and behaviours that can’t be monetised easily

As you can see I am beginning to lose the focus a little , which you didn’t do, well done.

Good points in the article but please, author and editor both, it was not a good idea to have a serious subject made into a ‘gimmick’ by following the letters of Trump’s name. Such a format belittles the content – and makes it bloody hard to follow because you aren’t following a cohesive thesis, you’re jumping round all over the place. How to deal with these personality problems is the question. Perhaps a follow up on those lines?

I was expecting a hand-writing analysis, but this was a bit ? 14 year old school girl-ish? And declaring he’s not qualified to diagnose Trump as a narcissist, but then calling him one anyway? Let’s face it, Trump is so out there, none of us need a degree in clinical psychology to diagnose him. Isn’t it Trump’s photo in the DSM5 in the section on narcissism?

Agree. Don’t think I’ve ever seen an attempt at serious political analysis structured as an acrostic before. Bit weird, Crikey.

I fully agree. It’s a serious topic, cheapened and minimised by the acrostic format (a technique most experiment with at primary school and then discard).

The trend is that those encumbered with such idiosyncrasies ARE being elected into office around the world.

The likelihood of Dutton being reelected is on a par with Trump. The public is comfortable with “hard bastards” and hence their electoral success.

It has been shown since Time immemorial that people prefer security to freedom.

To my mind, much as I agree with the analysis (although, as others have already pointed out, the author is only preaching to the choir. A Trump loyalist wouldn’t make it past the first paragraph) the core problem isn’t really Trump, it’s the systemic failures that have been exposed as a result of his first term in office. The political system of a democratic nation should not be so fragile that is vulnerable to the depravations of one bad actor, no matter what position he holds in government. The amount of damage Trump has dealt in just four years in office beggars belief, and he could still bring the whole country to its knees. If he loses the November election, I believe there’s at least a 20% chance the nation will be engaged in full-blown civil war before we’re half-way through next year. (And I hope – perhaps naively – that our government is taking note and planning accordingly for that eventuality.)

There are meant to be checks and balances built in to the system to prevent the kinds of abuses we’ve seen. These have proven to be largely futile when challenged. The major failing has been the US Senate, which is supposed to be the main check on presidential abuse of power. Republican senators have totally abandoned their oath to the country and constitution in their fawning sycophancy to their ‘great leader’ (they made their opinions of him clear enough prior to his nomination) and they are the true traitors in all of this. Trump can claim mental health issues. Not so the Senate – for them, it has just been naked lust for power.

Similarly, Congress has proven to be a toothless tiger. How many subpoenas did they issue during impeachment that were just ignored with no consequence?

The greatest pestilence in all this, though, has been the Murdoch press, particularly Fox News. Fox has successfully placed Trump supporters in a hermetically sealed bubble, without which Trump’s own inadequacies would have long since put paid to his political standing.

The Murdoch empire is a malignant cancer that threatens the heart of liberal democracies the world over, including our own. And our own government is doing all that it can to prop it up. That, too, beggars belief.

A good deal of analysis was undertaken in regard to the impeachment but most of it went unpublished. I know of two authors who had manuscripts rejected by The Guardian (and in Oz) and only a redacted view, from one author, saw the light of day for the NYT.

At worst there would be an impeachment but Trump was NEVER at risk of losing office. Yeah; I made some money there too.

Mate, I would argue that the implications of post-truth (to name one ill – Alt-Right or sovereign citizens anyone?) are a greater menace than anything concocted within the Murdoch world.

“… D is for Dictator… “

… and “Daddy Issues”? Freddie’s got a lot to answer for.

D also stands for Disillusionment – with a system that has failed the country (and the world) – while a Devious Trump holds out hope : for votes.

As for “D for Delivery”? Declined – like the country.

There’s just more Disillusionment, Disgust and Dreams —> Dust.

The Haves (including Trump) will not relinquish a share of their Dividend (that Trump is building) to close that Divide.

No thanks Crikey. With so much going on in Australia, devoting a whole edition to pointing out the glaring deficiencies of a foreign ruler is falling down on the job.

Keith and Rais, I fully agree with you.

Where is Crikey?

In the pit of Hubris.

Nailed it Rais. I’d feel better about today’s sad edition of Crikey if I thought the team had all just gone to the pub and had a long lunch.

Unfortunately, that’s not possible in Melb right now, so I’m not quite sure what the editor was thinking.

Lift your game Crikey!