If one of the key questions about the 2020 budget was whether the government was prepared to spend enough to support the economy, it was answered resolutely in the affirmative in Table 1 of Statement 1 of Budget Paper No. 1 which showed deficits totalling $480 billion stretching off to 2024.

The Grattan Institute had suggested the government needed to spend another $70 billion to $90 billion in 2021 and 2022 on top of its $180 billion in deficit spending already committed this year. Josh Frydenberg went way beyond that with another $112 billion deficit next year and deficits to the end of the forward estimates and then beyond into the forecasting haze of the late 2020s.

And the deficits aren’t just the result of lower tax revenue — despite justified criticisms that revenue forecasts still look too optimistic — but a massive expansion in the size of government.

But the other budget question is whether the spending will be effective and fair, to which the answer is not particularly, and no.

The strategy is a private sector recovery — driven by private spending by households, and business investment and hiring. The former will be funded by tax cuts that mostly go to high- and middle-income earners; the latter by a massive investment write-off allowance, retrospective tax losses and hiring subsidies.

The investment write-off, a monster version of the plan Labor took to the last election, will provide a necessary boost to business investment which deteriorated last year and fell into a deep hole this year — even if it merely brings forward a lot of spending that otherwise might have occurred in the next couple of years.

Something has to get business spending, and short of a miracle cure for COVID-19 this is about the best the government can do.

The income tax cuts, though, will achieve far less in terms of stimulus — especially if the virus remains a persistent threat that deters many consumers and workers from resuming normal activities, or what we used to think were normal activities in the world before the pandemic.

Many of us will save them, or pay down the mortgage faster, until we’re more confident that the economy is sound. Because the biggest cuts go to middle- and high-income earners that propensity to save will be particularly strong.

That might be OK if there were other forms of stimulus for household spending. The most effective form of stimulus, income support for welfare recipients, is limited to two small one-off payments. JobSeeker will — at least at this stage — still revert to its shameful pre-COVID level in January, against the advice of pretty much everyone across the political spectrum and even many within the government’s ranks.

The other no-brainer stimulus measure, funding for social housing, is also missing entirely. There is $2 billion for small-scale capital works and local infrastructure that — provided it doesn’t fall victim to the Morrison syndrome of being announced but never spent — should be spent quickly on roads across the country. That won’t provide much help for the residential construction sector.

And another easy win, greater and better funding for residential aged care — which would have supported the low-income earners working in that sector while addressing Australia’s greatest public policy scandal after climate inaction — has been kicked down the road. That’s despite the aged care royal commission urging the adoption of minimum staff ratios.

The targets of stimulus spending reflect a strong ideological bent — or, at least, a clutch of conservative clichés. It’s not government’s money, it’s taxpayers’ money. The best form of welfare is a job. We’ll never tell people how to spend their own money. We need a business-led recovery.

Except businesses and households won’t spend without confidence. And if the best form of welfare is a job, why are the hiring subsidies skewed to under-35s? What happens to older unemployed people?

Most of all, it’s not taxpayers’ money or the government’s money. It’s borrowings, eventually $1 trillion-plus. The Coalition has long made a virtue of increasing the tax burden on Australians and then theatrically handing a small chunk of that back as tax cuts in order to demonstrate its economic management. Now there’s nothing to hand back.

Every cent of the tax cuts, which will be permanent rather than “targeted and temporary”, is funded with borrowings for years to come, with budget deficits still at nearly 2% of GDP as the 2030s dawn.

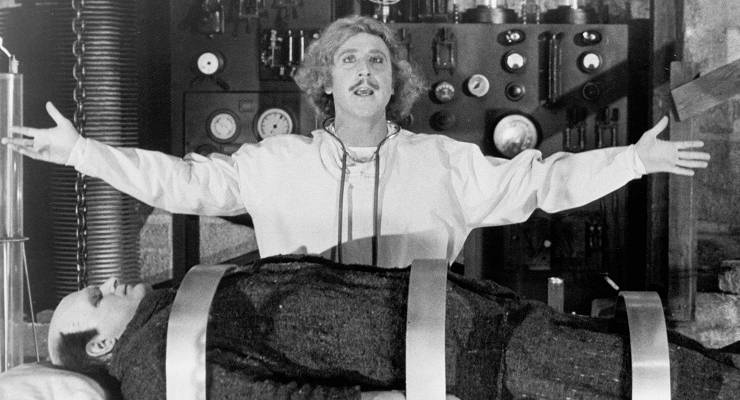

The result is a weird ideological mutant. The budget is a Frankenstein’s monster stitching together Keynesian stimulus with a neoliberal obsession with individual and corporate self-interest. We’re in a world of Prometheus Untaxed, a colossal expansion in the size of government to drive individual and corporate spending, one that leaves many of our most vulnerable behind.

What was your take on the budget? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication in Crikey’s Your Say section.

Scomo should change his name to “Krazy Kat” ala F troop.

Joshy reckons business should invest in a fleet of new trucks and farmers in a new harvester.

How does that support local manufacturers?

Food producers should invest in new production line equipment.

Where is the extra consumption coming from?

250million to modernise recycling.

My last job was in a recycling plant until it was sold for peanuts to a French company with a very dodgy reputation for peanuts.

They modernised it and sacked 90% of the workers mainly disabled, few of whom have found work since.

But big tax cuts for the well off will fix it….

Right, Koorong Joshy?

PS what ya gonna do with yours Joshy? New tennis court maybe?

Oh that’s right your club just built one with a sports rort!

The proposed deficit is much bigger than it needs to be because it is poorly-targeted.

Fiscal stimulus is all about getting increased demand in the economy.

The demand can occur by Govt spending more (infra), consumers spending more and business spending more.

With consumer spending, it works best when you factor in the Marginal Propensity to Consume – meaning give as much as you can to the poor because they will spend it locally and relatively immediately.

Tax cuts to the rich gives much less stimulus for obvious reasons, but that’s where the most money is going.

With business, tax write-offs and subsidies are not that effective because it shores up profits/dividends, bonuses and also leaks overseas.

During the GFC the Govt Payments as a %of GDP were 26% and that was regarded as an outrageous over-spend.

Now we’re asked to accept Govt Payments at 35% of GDP as prudent.

Give me a break!

The economy is an ungainly beast with the treasurer sitting astride its neck like a forlorn mahout trying to direct it along the most efficient path. We gather round the behemoth, blindfolded and feeling for the parts which will affect us most.

At least the LNP has accepted the importance of injecting a huge fiscal stimulus to the economy, but it seems this boost may be withdrawn prematurely.

it is regrettable that there has not been a greater focus on aged care and social housing, both areas of urgent need highlighted by the recession.

Personally, I would have liked more emphasis on mitigating climate change, environmental protections, renewable energy, electric car production, processing our minerals locally using our abundant clean energy resources and setting up a compassionate society where enterprise is reasonably rewarded, but those falling by the wayside are not disregarded.

Aged care and social housing will have to wait – as they always do – for Labor to return to power. This has the added advantage of allowing the Coalition to dump on Labor’s excessive expenditure and lack of fiscal discipline once they do it.

You have previously express the belief/hope that “Labor” will do things differently despite all evidence.

Could you hint as to whence this fantasy comes?

The Budget is a classic “Top Down” approach to the problems we in Australia face, no surprises here, thinly veiled trickle down economics.

If ScoMo &Co were building a sky scraper they’d start with the flag pole and the top floor, and do the soil test last.

Labor builds LNP destroys