The claim

The recent destruction of Indigenous heritage sites in the western Pilbara has brought the relationship between mining giants and traditional landowners into sharp focus, with a Senate inquiry under way to examine the actions of mining corporations.

Following a public outcry over Rio Tinto detonating explosives near sites dating back more than 46,000 years, BHP announced that it would not disturb its sites without further consultation with the Banjima people, the traditional landowners at its South Flank mine.

Liberal National Party Senator Matt Canavan immediately took to Twitter, arguing the Banjima people wanted the mine to proceed in order to create jobs in the area.

“This is the problem with a witch hunt,” he tweeted. “It always ends in an over-reaction. Mining employs Indigenous people at a greater rate than any other industry. You don’t help Indigenous people by stopping mining.”

As pressure mounts and former West Australian premier Colin Barnett calls for a royal commission into the destruction, RMIT ABC Fact Check investigates: does the mining industry hire Indigenous people at the greatest rate?

The verdict

Canavan is correct, but his claim does not paint a complete picture of Indigenous employment.

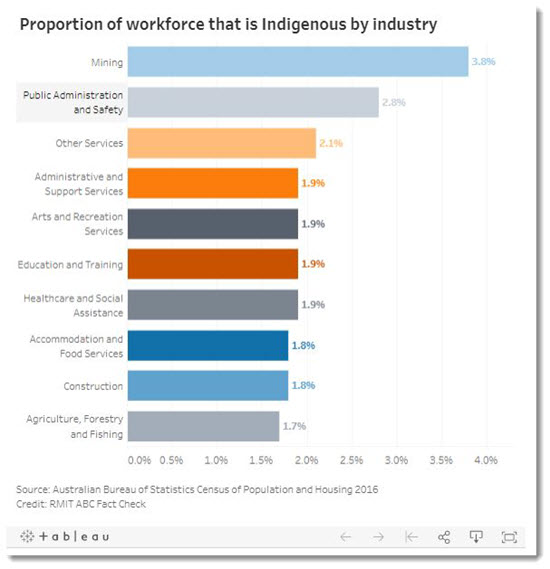

While the mining industry, as a proportion of its workforce, employs Indigenous people at the highest rate, it’s important to note that many more Indigenous Australians work in other sectors of the economy.

According to census data, Indigenous Australians account for 3.8% of the mining workforce, well above the average of 1.7% for all industries.

The next highest workforce representations of Indigenous people are in public administration (2.8%) and in a category called “other services” (2.1%).

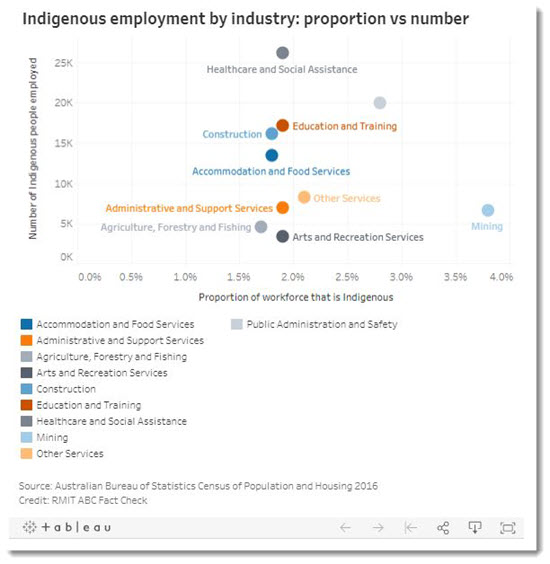

However, while mining employs 6,652 Indigenous Australians, nearly four times that number work in healthcare and social assistance (26,178).

Almost 20,000 Indigenous people also work in public administration and safety, and 17,176 in education and training.

Although the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) cautions that the census may undercount the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, experts said it was still the most reliable means of assessing Indigenous employment.

One expert also noted that although mining is a major employer of Indigenous people, increasing automation in the industry posed a greater risk to Indigenous jobs than stricter rules around protecting cultural heritage.

What the figures show

Census data is the most reliable measure for testing Canavan’s claim, experts spoken to by Fact Check said.

This is despite the fact that the data may undercount the Indigenous population by as much as 17.5%, according to the ABS, which collects and analyses the data.

Michael Dockery, an associate professor in the School of Economics and Finance at Curtin Business School, told Fact Check that “as Indigenous people represent only around 3% of the population, most sample-based surveys don’t have enough Indigenous respondents to make accurate inferences”.

Francis Markham, a research fellow at the Australian National University’s Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research told Fact Check that in the absence of alternative data, relying on percentages broadly allows for any undercounting because “it assumes that somebody who is not counted is equally as likely to be hired across a range of industries as someone who is counted”.

The census data shows that Indigenous Australians account for 3.8% of the mining workforce, well above the national average of 1.7%.

In percentage terms, the next highest workforce representations of Indigenous people were in public administration (2.8%) and a category known as “other services” that includes industries such as repair and maintenance and professional services (2.1%).

However, when Indigenous employment is measured in absolute numbers, the picture is very different because mining employs relatively few people overall.

In 2016, the mining sector employed around 177,640 people, of whom 6,652 were Indigenous.

By contrast, industries such as healthcare and social assistance are much bigger employers: a total of 1,351,018 people were employed, of whom 26,178 were Indigenous.

Likewise, construction employed 911,058 people, including 16,160 Indigenous workers.

Why the controversy?

Rio Tinto’s destruction of the two Juukan rock shelters in May was widely criticised as being irresponsible. Shareholders were among those who condemned the blast, triggering a board review of its cultural heritage management and resulting in an executive purge, including Jean-Sébastien Jacques, who stepped down as chief executive.

The blast has raised questions over the adequacy of legal protections for Indigenous heritage sites.

John Ashburton, chair of the Puutu Kunti Kurrama (PKK) Land Committee, which represents the area’s traditional land owners, said the loss was devastating.

“Our people are deeply troubled and saddened by the destruction of these rock shelters and are grieving the loss of connection to our ancestors as well as our land,” he said.

Ashburton said the PKK recognised they had a long history with Rio Tinto but expressed frustration that Section 18 of the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act prevented new information, such as the historical significance of the rock shelters, from being taken into consideration.

“We recognise that Rio Tinto has complied with its legal obligations, but we are gravely concerned at the inflexibility of the regulatory system,” he said.

The Banjima Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, which represents the traditional landowners at BHP’s South Flank mine, also expressed concern about the ability of WA’s Aboriginal Heritage Act to be able to protect culturally significant sites.

The corporation told the Senate inquiry that agreements had “historically been negotiated in an environment of an extreme imbalance of power”.

BHP has established a Heritage Advisory Council to inform future decisions regarding its South Flank mine.

Former WA premier Colin Barnett, whose government granted the right for the sites to be blasted, said that a Senate inquiry investigating the destruction was insufficient, and that Rio Tinto and successive governments had both failed to meet their responsibilities to protect Indigenous heritage sites.

The bigger picture

While the resources sector accounts for some of Australia’s top exports, its contribution to employment is often misconstrued.

ANU’s Dr Markham said: “The mining industry isn”t the biggest employer of Indigenous people — this line is often misinterpreted.”

Curtin University’s Dr Dockery said that the main contribution from mining to Australia’s economy was not related to jobs.

“Mining is critical to the Australian economy in terms of output and particularly in terms of the value of exports, but because it is extremely capital-intensive, it has a relatively small share of employment that belies its economic importance,” he said.

Despite the strength of the economy pre-pandemic, and continuing strength of mining exports, Indigenous unemployment overall remains high. The government’s 2020 Closing the Gap report found that the program had fallen short in reaching the majority of its targets, including for employment.

“The target to halve the gap in employment outcomes within a decade was not met,” it said.

It found that in 2018, the Indigenous employment rate was around 49% compared with around 75% for non-Indigenous Australians.

Future prospects

Queensland University emeritus professor David Brereton, a resources sector expert, told Fact Check more research was needed at a national level to understand how jobs were being distributed.

Dr Bereton said there had been a concerted effort by mining companies to hire and retain Indigenous staff. But localised research conducted at the former Century mine in the Gulf of Carpentaria had shown that not all employment figures were equal in value.

“Some of the companies that were improving their Indigenous employment rates were often just recycling from the pool of people who were already experienced.”

“The real measure of impact and benefit is whether you are giving jobs to people that hadn’t been in the mainstream labour market — and whether they stay in work after,” he said.

Dr Bereton said this metric was critical to understanding the true value of employment but was rarely tested.

He also flagged a potential risk that automation posed to the future employment prospects of Indigenous people in the mining sector — especially when it came to iron ore.

“Of all the factors that are going to make it more challenging in the future, stricter rules on cultural heritage would be down the list,” he said. “It’s more likely to be factors around automation and remote operation.”

A report tabled in 2018 by UQ’s Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, identified Indigenous people as being the most vulnerable to a decline in the need for entry-level and semi-skilled jobs in the sector, especially in remote areas where fewer alternative employment options were available.

Regional and gender dimensions

Indigenous employment in the mining sector is unequally distributed along gender lines and in terms of proximity to major cities.

Consistent with the non-Indigenous workforce, gender plays a significant role in both the likelihood of being employed and what types of work are being undertaken.

A report produced by the Australian National University, based on census data, found that around 80% of the Indigenous workforce in the mining sector was male.

Another recent study, published by the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, found that disability, education and the history of incarceration were among the most important factors impacting labour force participation, but that some of these disproportionately affected women.

“The labour supply associations with education and incarceration are greater for females than males,” the study noted.

More broadly, the census data showed Indigenous females were less likely to be employed than males overall, with 44% of males employed compared with 41% of females.

Indigenous people living in remote areas were much more likely to be working in mining, accounting for 23.1% of the Indigenous workforce. In regional areas, it accounted for 6.7% and in major cities, 3.7%.

Principal researcher: Sonam Thomas

Sources

- Banjima Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, Submission to the senate enquiry inquiry into the destruction of 46,000 year old caves at the Juukan Gorge in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, 14th August 2020

- BHP, BHP agreements with traditional owners in Australia, 16 September 2020

- Matthew Canavan, Twitter part 1, 11 September 2020

- Matthew Canvan, Twitter part 2 11 September 2020

- ABC News, Former WA premier Colin Barnett calls for Juukan Gorge royal commission, 18 September 2020

- ABC News, Pilbara mining blast confirmed to have destroyed 46,000yo sites of ‘staggering’ significance, 26 May 2020

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, G51 Industry of employment by age by sex,

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2071.0 – Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia 2016

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Census: Industry, 2017

- Office of the Chief Economist, Resources and Energy Quarterly, June 2020

- Australian Archaeological Association, Loss of Juukan Gorge Rockshelters, Pilbara region, Western Australia, 28 May 2020

- The Guardian, Rio Tinto condemned by shareholders for seeking legal advice before blowing up Juukan Gorge, 8 September 2020

- Rio Tinto, Rio Tinto Executive Committee changes, 11 September 2020.

- Australian Government, Closing the Gap Report 2020

- University of Queensland, Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, Indigenous Employment Futures in an Automated Mining Industry 2018

- Y Dinku and J Hunt, Factors associated with The Labour Force

- Participation Of Prime-Age Indigenous Australians, 2019

- Australian Bureau of statistics, Census of Population and Housing: Characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians 2018

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population and Housing: Understanding the Increase in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Counts 2018

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.