After yet another polling miss, is it time to ask: what’s their point? Have they just become a journalistic bulk-weight, filling up space, drawing attention, taking up time?

Sure. They retain their value as emotional insurance in an age of uncertainty. Better than a psychiatrist, really. Over the past year, they’ve soothed the world that everything would be OK, that as Joe Biden says repeatedly, “America is better than this”.

They’re like modern morality plays, bulking out the media product with comfort readers crave. No wonder media outlets here and around the world are keen to put their brands on them and pay the cost.

Worried about Donald Trump, climate change, COVID-19 lockdowns? No problem: so, it seems, is everyone else. It’s sure to work out.

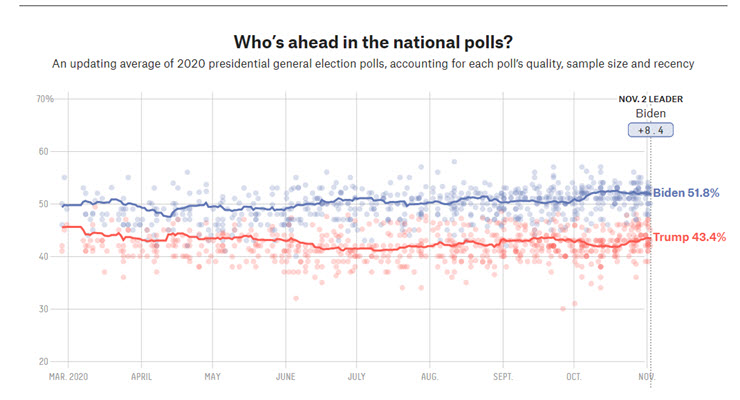

Polls — even this week in the US — are not necessarily “wrong” about what they’re measuring. Biden’s popular vote margin probably will end up around the average forecast of 6-7% with an electoral college vote at Obama levels.

But even when they’re “right” at the national level, they’re wrong at the local or fragmented level where journalists need to tell the story. They encouraged a binary understanding, in this case, of the US and Trump. But they miss the underlying reality that the election exposes: just about no one has changed their mind.

Over the past four years, older voters have died, younger voters have turned 18, people move, voting has become harder in some places and easier in others. Shake it all up, and the needle shifts. Journalists will now turn that accidental outcome into a new collective wisdom about America.

Future polls will shape — and be shaped by — that new wisdom. They’ll be weaponised into political conflict as they have been in Australia. (Remember the 30 consecutive Newspolls test that doomed both Abbott and Turnbull?)

Polling misses also cost real money: just this past month, billionaire Mike Bloomberg threw $100 million into Florida off the back of positive Biden polls. Lucky he can afford it.

After each miss, polls are reshaped in an attempt to catch the falling knife of social change. After the 2016 US presidential election, pollsters started weighting by education to reflect the emerging bifurcation between educated and uneducated white voters, long after Trump had intuited it. (“We love the uneducated,” as he crowed early in the 2016 campaign.)

But polls are getting worse, not better, because society is becoming worse — more fragmented, less social. Pollsters are increasingly reliant on weighting of more and more shifting social groups divided by gender, race, class and age and less on the input from a diminishing number of people who actually talk to them — about 8% in the US this year.

Blame the internet: once, home landline phones were ubiquitous and inquisitive pollsters were rare. Now, it’s the other way around. Blame people: they know the game and come up with answers they think are “correct”, taking their cue on issues from what their political representatives say.

In the media, political journalists and forecasters have been adapting in a to-and-fro between reality and the polling house of mirrors. There’s the more-is-better approach of polling aggregators, like Real Clear Politics. These end up both played with rubbish polls (garbage in, garbage out) and encourage pollsters to herd around acceptable differences.

The wisdom of betting markets was thought to be a useful substitute. But without any insider knowledge, these have become just another derivative of polls. Their conservate bias also shows a wish-casting by people with more money than cool judgement.

The latest attempt to breathe life back into polls is probabilistic forecasting, most famously the FiveThirtyEight model of Nate Silver or The New York Times’ UpShot. These forecasts mesh the tools of polling and betting (and investment) markets to determine how “likely” particular outcomes are.

They more properly grasp uncertainty. But it’s unlikely that they’re read that way. Silver is recognised for predicting Trump had a 30% chance in 2016. Bookmakers gave Queensland about the same chance of winning the State of Origin last night, and no one considers that a correct call..

In a more sober approach to public opinion, the worst outcome will be a journalistic reliance on feelings (aka, the pub test). Polls saved the media from that once before.

Rather, journalists have to give up trying to guess what’s going to happen in rare frequency events (like elections) and focus more on reporting the diverse and changing society that’s happening in front of us right now.

Actually I wonder whether the polls and the pollsters were caught out as appears to be the judgement of media pundits. From my reading, the pollsters reported that Trump supporters would turn out strongly on Election Day, but that the initial lead would be drawn back with the counting of the Early Mail votes which favored the Democrats. Judging by the results, that seems to be the case. The so called ‘blue wave’ hysterical interpretation was made by the media commentators not the pollsters.

journalists have to give up trying to guess what’s going to happen in rare frequency events (like elections)

I’m afraid it’s symptomatic of the media’s tendency to treat politics as similar to sport (Who’s winning? What’s the score?) rather than taking the effort needed for

reporting the diverse and changing society that’s happening in front of us right now.

The questons that are asked have been answered copious times here at Crikey AND in more specialised forums; to say nothing of degree coruses at up-market universities.

In a nutshell, Chris, the data that is obtained nowadays, given the questions (some plain idiotic or indeed ambigious) is highly correlated. One can not extract definitive info from correlated data.

Indeed the demographis do change each four years or so but places who are experts at tapping information from the market (e.g. HSBC) spend a heap of coin doing so. That expenditure, I suggest, is well beyond (e.g.) news corp. {I’m told that a reporter, nowadays, might or might not be assiged a camera guy for an interview – but I can’t say).

There is an entire field known as “machine learning” devoted to this kind of stuff but it is (1) relatively new – about a decade or so and (2) can be compromised by the data; rubbish in => rubbish out!

There is considerably more to the topic but rhetorical questions directed to a clueless public provide no service and display no maturity whatsoever.

“journalists have to give up trying to guess what’s going to happen in rare frequency events (like elections)…”

That’s a fine wish, but I guess what’s going to happen is that nothing much will change. The credibility of polls must now be as low as it has ever been, but there are always fortune tellers, soothsayers, divinators, augurs and the like prognosticating to the gormless multitude after much mysterious mumbo-jumbo, so why should being demonstrably useless stop pollsters or the journalists who report them? So long as anyone is willing to read / click on such articles they will be published, and they will continue to do mischief.

Face to face polling by experienced staff with properly tested questions and statistically valid sampling always gives a true picture of voting intent. But it is too expensive and too hard. Today’s half-baked pollsters prefer more group discussions, phone and media polls, suspect modelling techniques, data aggregation and so and so on……….

we won’t quibble but there is the vexed issue of a confidence interval but I agree : more or less.

Then again we should not be too surprised. We were warned long ago by no less an authority than Yogi Berra (allegedly):

“It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”