The exuberance of stock markets in 2020 appeared at times irrational. As 2021 begins and economic prognostications turn foul, frothy financial markets begin to look positively lunatic. This week, the US S&P 500 of top stocks hit yet another record high, as did the UK market.

Rising markets were perhaps not the immediate response expected by the authors of a newly released World Bank flagship report. The report, on global economic prospects, contained grim portents:

Global growth is projected to moderate to 3.8% in 2022, weighed down by the pandemic’s lasting damage to potential growth. In particular, the impact of the pandemic on investment and human capital is expected to erode growth prospects in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) and set back key development goals.

It warns of a “decade of disappointment”. The authors of the report set out to put happy-go-lucky attitudes in historical context. They describe a repeating pattern where over-optimism abounds as we emerge from recessions, only to be followed by crushing reality.

“Past recessions were typically followed by several years of disappointing growth outcomes and downgrades of long-term growth expectations,” the authors write.

“Years of initial over-optimism and subsequent disappointments have not been limited to global recessions. Even after country-specific adverse events, long-term growth forecasts for the countries concerned had to be repeatedly downgraded.”

So who can tell the future better? Economic wonks from a global institution or the collective wisdom of financial markets? Neither have terrific records. Both are subject to regular humiliating reversals. But in this case, financial market ebullience seems to have more to do with low interest rates and a lack of other investment options rather than true belief the future will be brighter than ever.

We would do well to heed the sober voices emanating from World Bank HQ. They are telling us that if we don’t take action, we will be stuck a world in which economic growth is lower than in the past.

Why does low growth matter? Because it affects human wellbeing. Lower growth makes more poverty and more unemployment. With all the political ramifications those bring.

In the less developed world, low growth means progress on poverty reduction gets stuck. In the developed world, including Australia, it means lower than expected growth, higher than expected unemployment, weak wages growth and high underemployment.

Such a pattern neatly describes the last decade, the one in which we emerged from the global financial crisis (GFC). Australia’s economic health has never quite recovered to levels seen in 2008. Our underemployment rate, for example, was as low as 5.7% in 2008, but as high as 8.5% in 2019.

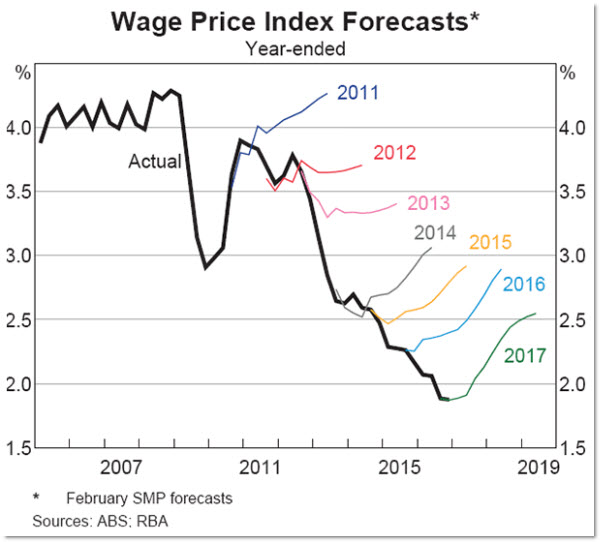

The iconic image of Australian over-optimism of the post-GFC period may well be this chart, produced by the RBA, showing how it never stopped believing in surging wages growth, despite all the evidence none was to be found.

Now underemployment is higher even than it was in 2019, and wages growth is lower. If our expectations of a return to normal are wrong, that leaves Australia in a particularly parlous position because our “normal” wasn’t very good. There’s little room for wages growth to get worse from here without falling into negative territory.

How would you like a decade of pay rises that don’t keep up with inflation? And what would that do to the political landscape? Populism would be ascendant and for politicians, straying from a laser-focus on the cost of living would be fatal. Long-term policymaking would take a back seat.

Growth is good not only for its immediate wellbeing benefits but because it gives us a buffer to lift our eyes to the horizon and plan — not least for issues like climate change.

But growth will be harder to come by, for two main reasons. Businesses have stopped investing, and the pandemic has badly damaged human capital. Economic output comes from two places: capital investment — the building and maintenance of shops and factories, machines and vans, etc — plus the skill and diligence of humans. The pandemic has harmed both.

The UN is calling it “the largest disruption of education systems in history”, and it is likely to leave millions with lower education levels than would otherwise be the case. School completion is expect to plummet in less-developed countries, harming those countries’ long-term growth prospects.

For people who care about global poverty, among the many grim prognostications in the new report is the warning of debt crises in less-developed countries.

For now, unprecedented monetary policy accommodation has calmed financial markets, reduced borrowing costs, and supported credit extension. However, amid the economic disruption caused by the pandemic, historically low global interest rates may conceal solvency problems that will surface in the next episode of financial stress.

Debt crises in countries that try to control the value of their currency are particularly damaging as they often force rapid devaluations in the currency, making imports expensive and putting many essentials like food and fuel out of reach of ordinary people.

Greece, Argentina and Venezuela all illustrate the tremendous risk of debt and currency crises. More such episodes could punctuate the next decade.

If Australia is cruising for a fall, there are countries that could fare even worse.

Probably for the first time in our history, this present generation, 21 to 39 will have a lower standard of living than their parents.Home ownership is already becoming an impossible dream for a majority of lower paid workers.However, has anybody equated this fact to the low union membership late in the private sector? The employers are increasingly being able to forestal meaningful wage rises and even in some circumstances avoid paying their employees the correct wage as there is no surveillance from shop stewards or union reps on the work site.

if we don’t take action, we will be stuck a world in which economic growth is lower than in the past.

It can’t go on forever, you know.

Yes, the bullshit of perpetual growth.

Globalisation was a marvellous sugar hit, but with a very bitter after taste. Moving jobs to countries with few or no workers’ rights gave us cheap goods, but denied local youngsters in developed a whole of lot of work opportunities, forcing them into unproductive or unmeaningful work, and with no ability to bargain for higher wages. It is also allowing China to displace the West in the global leadership stakes. Highly addictive, and making a few very rich, but ultimately very toxic for developed countries now in decline.

If wage growth will be low and, as Piketty claims, the returns to capital exceed returns to labour, doesn’t that mean it makes more sense for individuals to invest in assets than improve their own human capital?

A kind of dumbing down that will result in less innovation (the driver of growth) and lead to a vicious circle?

That paints a picture of a “developing” country economy, doesn’t it?

“Why does low growth matter? Because it affects human wellbeing. Lower growth makes more poverty and more unemployment. With all the political ramifications those bring”

Of course, all that could be managed by taxing the exceedingly wealthy and multi-national corporations, and redistributing it back via realistic unemployment benefits, or god forbid a universal basic income.