Just before Christmas, the week-long summit of the Communist Party of Vietnam — Asia’s other major communist-run country — was held to determine its top leadership for the next five years, to be unveiled at the bumper national congress later this month.

Vietnam has emerged as a major economic and strategic player in Asia in recent decades so its politics — which get little attention in the West — are important beyond its borders.

Australia’s relationship with the country has blossomed in the past decade. Two-way trade is booming and was $15.5 billion in 2019. It has almost tripled in 10 years, making Vietnam Australia’s 14th largest trading partner. And in March 2018 Malcolm Turnbull signed a strategic partnership. Its 100 million-strong population and swelling middle class is seen as a major export prospect as China tightens the screw on Australian goods and services.

The country has outperformed other major economies in the region — Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore — in recent years. Its manufacturing sector is booming and it is becoming something of a technology powerhouse.

It has also been successful in preventing the spread of COVID-19, at least until now, leaving it with expected GDP growth of 2% to 3% for 2020.

Vietnamese-born Australians also represented the sixth largest immigrant group, with more than 250,000, in mid-2018, and the number of Australians with Vietnamese heritage is several times larger.

Vietnam has drawn closer to its former rival the United States over the years (particularly when Democratic presidents sit in Washington) and remains close to Russia, which it has long used to balance the power of China to its north.

In October it became the first country — with Indonesia — to be visited by Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga only a month after he stepped into the role.

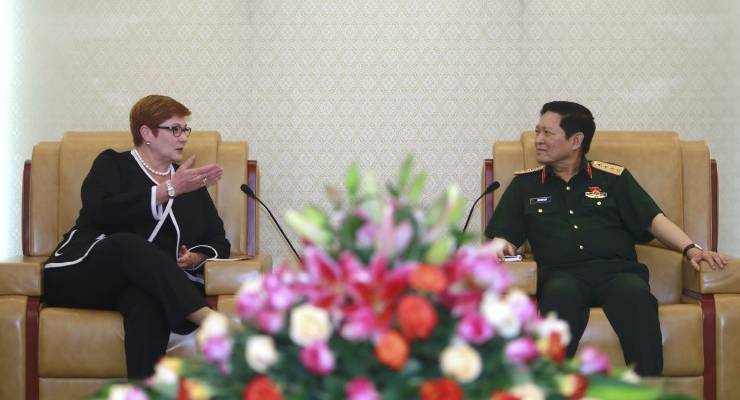

Australia has increasingly close defence ties to Vietnam, with defence ministers committed to meeting each year.

For 1000 years of its history a vassal state of China, Vietnam has long tried to carve an independent path from its northern neighbour and has been more aggressive in the fight for territory in the South China Sea than most. Anti-Chinese street protests are not uncommon as anti-Sino sentiment in the country remains high.

Yet its political structure is very similar to China’s with a ruling politburo of 19 pulled from the Communist Party of Vietnam’s (CPV) central committee. But the real power lies in the leaders of the so-called “four pillar” system that was instituted in the 1990s to ensure the roles of party general secretary, prime minister, state president and national assembly chairperson (from most to least powerful) were held by different people.

This was to prevent the emergence of a supreme leader under the self-described “democratic centralism” of the consensus-based leadership that Marxist-Leninist parties try — and so often fail — to achieve.

Another goal of the four pillars was to balance the representation at the top of CPV from the various regions of the country: north, central and south. The system changed in 2018 after General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong added the more ceremonial post of state president following the death of his predecessor, making him the most powerful Vietnamese leader in decades.

Trong led the party’s more conservative faction in toppling former prime minister Nguyen Tan Dung, who was the driving force behind the nation’s fast and loose economic growth. Since then Trong conducted a comprehensive anti-corruption drive that has seen thousands of current and former party cadres arrested and jailed, including a politburo member and powerful Hanoi party chief.

Still, amid its many successes, Vietnam’s plans remain unclear — the results of voting last month have been tightly held. Most analysts see the battle for the top post of party secretary between business-friendly current Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc, 66, and an array of other ageing leaders and security figures who may get the backing of the ailing Trong.

Trong is expected to be pulling strings behind the scenes if indeed he steps down.

But beneath its booming economy and a convenient enmity towards China — particularly in the present context where the relationship between Australia and China is at historic lows — lies a similar ruthless authoritarianism.

Hanoi has long conducted campaigns against its critics as well as programs of repression of religion and ethnic minorities. As in all communist regimes the media is heavily censored and surveilled; this has become more worrisome in recent years, aided and abetted by self-censoring US tech giants Facebook, Google and YouTube.

Until recently, Australia studiously ignored China’s human rights abuses as trade between the two countries boomed in the years after the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

It seems Vietnam is also too important for the government to speak out against a country whose strategic and economic importance to it is quickly growing.

This ‘analysis’ is a joke, right? Sainsbury’s having a lend, surely?

“Australia’s relationship with the country has blossomed in the past decade. Two-way trade is booming and was $15.5 billion in 2019.”

Gee, $15 bil?!

Dose of reality;

Vneexpressdotnet (‘Vietnam’s most read newspaper’), Nov ’20, headline;

“China-Vietnam trade soars past $100 bln”

&

“…Vietnam exported $37.9 billion worth of goods to China in the first 10 months, up 14.8 percent year-on-year, and imported $65.6 billion, up 5.9 percent, according to Vietnam Customs….

The value of two-way trade has thus risen to $103.5 billion, making this the third consecutive year that Vietnam-China trade value has crossed $100 billion…..”

Yunnan – to Singapore railway ring a bell.

5,500 km, taking in Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore.

Will link to the lines that are already operating from China, through Russia, and on to Hamburg, Germany. JV formed over a decade ago, involving China, Russia and Germany.

Ultimately, Singapore to Spain, by rail.

Wow! Another big one from the boys who brought us Covid-19. Sure to be as successful as Sinovac. Have you had your shot yet?

Having worked in Vietnam over 5 years in the mid 90s and also in China since early 2000s, there was one fundamental difference in the political systems that made a difference in dealing with the bureaucracies of each. In Vietnam, residents at village level voted for representatives on their local committee. However, in China, local representatives are chosen by the party. This difference flowed through to the National Assemblies so that in Vietnam there were non-party representatives, unlike China.

While both systems can be very frustrating to foreigners trying to do business, I think Australians have more in common with the Vietnam system as dissenting opinions are more common and tolerated better. The main problems I encountered in Vietnam were an almost defunct industrial sector at that time, an over-reliance on foreign aid and relatively fewer opportunities in my industry (mineral exploration). I know this has changed dramatically in many sectors although not uniformly. With the current Australia-China diplomatic situation, I think strengthening ties with Vietnam would be much easier culturally and politically and probably economically more attractive.

Is time we kicked China to the curb it is so shalliw that it is out of it’s depth.

Bans all things Australian and when we stop it from investing in certsin areas it cries foul.

Little bit hypocritical me thinks.

China is about as shallow as Australia and less hypocritical. We interfere in their internal affairs, discriminate against foreign investment from them, start a worldwide smear campaign (from China’s perspective), can’t take criticism when we commit war crimes or our own human rights violations (First Nations and Immigration Detention) and then we get offended when China takes a lead out of the US playbook and imposes sanctions on us? I am a proud Australian but we are a racist country that thinks we are superior to other nations. Newsflash: we are not. We are a middling power (not a Middle Power) that is a Trading Nation and need to understand that we are a part of Asia amd need to start fitting in. The current Limited News Party Hillsong Scotty Government is solely responsible for the destruction of our relationship with China. We need to realise that we are all mouth and no trousers in any economic relationship with a superpower. The Septics only tolerate us as long as we toe their line. Australia needs to learn to be more like Singapore and focus on business.