After a reshuffle of Labor’s shadow cabinet on Friday ousted long-term incumbent Mark Butler from the climate change portfolio, pressure is mounting on Anthony Albanese to resolve party tensions over emissions reduction.

But climate isn’t the only policy tussle Albo will need to adjudicate ahead of a rumoured spring federal election. Another is negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount.

Some MPs and commentators blame such redistributive tax proposals for Labor’s unexpected election loss in 2019. Such concerns culminated in Labor officially dropping its controversial franking credits policy in January.

Recent pieces in The Australian and the AFR have put pressure on Albanese to cave on housing-related tax concessions too. While he insists a decision is yet to be made, there is a “developing view” among Labor insiders that these policies will also be dumped.

But just like on climate policy, Labor’s leadership team should ignore the proponents of capitulation, who remain unconvincing on both the political viability and economic imperative of taming the exponential growth in capital city house prices.

Negative gearing did not lose Labor the election

First, reforming taxation of valuable assets is not the electoral poison some make it out to be.

Labor announced its plan to end negative gearing tax concessions for future property purchases and halve the capital gains tax discount in early 2016. A few months later the party almost toppled the first-term Coalition government, picking up 14 seats and reducing Turnbull’s majority to one.

But after Labor’s 2019 election loss, some hypothesised its negative gearing position might have produced a delayed backlash among voters. However, statistical analysis commissioned by Labor for its official election post-mortem “had not been able to identify either [negative gearing or franking credits policies] as significant vote changers in their own right”, and found higher-income urban voters most likely to be affected by those policies had swung towards Labor.

The real problem, it concluded, was that the slew of complex policies confused and frightened some voters, and Shorten’s flaccid leadership failed to allay their suspicions. The policy substance was not the issue; the strategic communication was.

Property market in unstoppable death spiral

Labor has changed its leader and pared back the size of its agenda (indeed many argue it is now too “tiny”), but the moral imperative to find room in its platform for tackling housing inequality has only increased.

The Domain house price index, released last Thursday, shows prices grew last year despite our economy experiencing the deepest recession since the Great Depression and the steepest decline in population growth in decades.

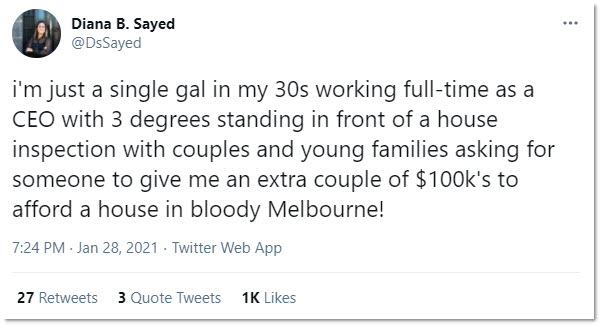

Median house prices hit a record $852,940 by year’s end, with Sydney’s median surging to a staggering $1.21 million.

Some wishful reports in early 2020 predicted a golden opportunity for young people to snap up homes during the pandemic. Indeed first-home buyers have hit their highest level since the GFC, suggesting some did leap at the initial opportunity presented by fewer and less confident competitors at auctions.

But housing experts argue this is likely to be a short-lived reprieve that mainly benefited high-income earners who had almost saved enough for a deposit anyway.

“For essential workers and aspiring first-home buyers, the hurdles are harder than ever,” University of Sydney urban planner Professor Nicole Gurran told Domain.

Australia was not the only country to see rapid property price growth last year. Investors across the globe threw cash at assets with relatively stable futures amid an uncertain business environment.

Accordingly, media attention is again turning to whether deposits are just too damn high for aspiring owner-occupiers.

Federal government must wind down the gravy train

The Victorian government’s recent social housing commitment, and the NSW government’s transition from stamp duty to land taxes and fast-tracked metropolitan construction, will help modestly slow the spiral.

Other piecemeal reforms such as Morrison’s HomeBuilder and build-to-rent plans probably won’t hurt, but will struggle to make an imprint.

The biggest driver of Australia’s unsustainable house price growth remains the decades-long crowding out of owner-occupiers by speculators and rent-seeking investors.

Any political party serious about tackling inequality across classes and generations must commit to restraining investors’ involvement in the fundamental human necessity of housing. Removing our uniquely regressive tax concessions is an obvious place to start.

Albanese grew up in public housing so knows intimately the importance of the government ensuring a roof over citizens’ heads. Hopefully he recalls its impact when the usual cynics argue the price of winning over working- and middle-class voters is dooming their children to perpetual rental stress.

As you implied through your comment about Shorten’s flaccid leadership, the problem with taking significant policy change to an election is that you also have to persuade those voters that might agree with you that you have the political resolve, nous and party unity to deliver on those policies. Otherwise you simply harden the opposition amongst the voters who don’t agree with your policy positions without generating a corresponding resolve amongst the voters that do agree with you.

I’ve never understood the halving of tax for those who sit on their arses and watch their capital gains roll in taxed at half the marginal rate, when people who work hard with their hands to earn their money pay full tax. Can someone justify this fat bum gets the better deal policy?

When first introduced in 1985, capital gains tax was levied on the real capital gain. That is, the difference between the selling price and the purchase price of an asset, indexed against the CPI over the intervening period. John Howard decided to simplify this and introduced the 50% discount, abolishing indexing. It would be interesting to see how much tax revenue this has cost the budget over the past decade or so, given the low rate of CPI increase, but big increases in asset prices.

Same for inheritances. Most wealth is inherited, and yet the tax on this freebie is zilch. Most other developed countries have inheritance taxes, and so should we, with suitable exemptions for farms and small businesses that need to remain viable. They can be taxed when they’re sold outside the family.

True Peter, and the threshold can be set very high. Unfortunately a scurrilous Facebook campaign did the Labor government in last election, it was significant, but Shorten’s moribund ‘nobody’s man’ schtick brought him unstuck.

In all the discussion of the ever rising price of housing in Australia, practically no-one mentions immigration. Surely it is simple maths that if we bring in over 100,000 people each normal year, and do nothing to make sure that there is adequate housing for that increase, there will be an issue of supply not meeting demand? And that will inevitably result in increasing prices?

No, I am not against immigration, I am against the absolute lack of planning around the increase in population.

Consider the trends in NZ in a year of zero immigration but some slight increase in population as NZ citizens and residents return over 2020; indeed Perth from about three to four years ago. The matter cannot be reduced to a single issue Aileen.

And in a contrary opinion, of course immigration is a significant factor. Not the only one Aileen, but significant.

“strategic communication”, is the key, and not giving the Neocon media too great a target to spread fear/smear campaigns.

One extra house in a country as wealthy as ours is probably a sensible investment for retirement, any more and you are impacting on other’s right to own a home significantly.,

Stealing the opportunity for a sense of security from families in the future is the kind of emotive slightly, a lifelong rent cycle trap.. underhand approach Labor needs to adopt, but only when provoked.

Negative gearing isn’t a topic I would bandy about too much.

Serious incentives to lower rent and beefed up tenent security low environmental impact, high insulation values are other tools required, rent/owner dwelling ratios for neighbourhoods.

Greed/selfishness , it’s about me not us , is manifest in

neo conservative values and our media has had at least 3 generations to sell their message.

Remove -ve gearing and apply an imputed tax (30%) on gains over the this century and the ills that you identify will become much ameliorated.

The new Shadow Minister for decarbonisation etc should hit the ground running, calling for ideas from academia. An international energy revolution is imminent, with hard commitments to removing emissions from power, but only vague commitments to the harder problems. However there are engineering solutions for the hard problems – steel, cement, chemical feedstock, and synthetic fuels for shipping, aviation and farming. Turning an academic possibility into a economic activity requires engineering research and development. As long-term processes these require leadtimes of several years of proposals, papers and conferences. Labour can get the academics moving forwards before they even reach office. Leadership is indicated and required.

Totally agreed Roger, an international energy revolution is coming. Words from Twiggy Forrest resonated with me, although I believe very little that he says. His thoughts were along this line, that when it comes it will be quick, not slow. Old industries will be left moribund. The new destroys the old, as it should be.