The governmental organisation in Australia that does the longest-term planning is now, apparently, the Reserve Bank (RBA).

On Wednesday, Australia’s chief central banker, RBA governor Philip Lowe, told the National Press Club that the economy was so far off track the bank would keep interest rate settings fixed at max stimulus for the next three years, and possibly longer.

It’s now talking 2024 for the timing of its next move in interest rates. That’s bloody miles away. It’s planning further ahead than the International Olympic Committee, which used to have the next 12 years locked down but now doesn’t know what’s going to happen in July.

The RBA board will not raise interest rates until inflation is back over 2%, it has promised. And an upwards blip in inflation will not be enough to perturb this plan. Inflation needs to rise sustainably.

“It is difficult to determine exactly when this condition might be met but based on the outlook I have discussed today we do not expect it to be before 2024,” Lowe said. “And it is possible that it will be later than this.”

For a central bank, this is radically long guidance. Usually it reserves the right to change policy settings at each board meeting — of which there are 11 scheduled a year.

The 2024 deadline also represents an apparent extension of how long interest rates will be at rock bottom. When the RBA first committed to leave rates low for three years it was 2020. Instead of letting the clock run down, it is still committing to three years and suggesting it might be three years plus.

What’s the reason?

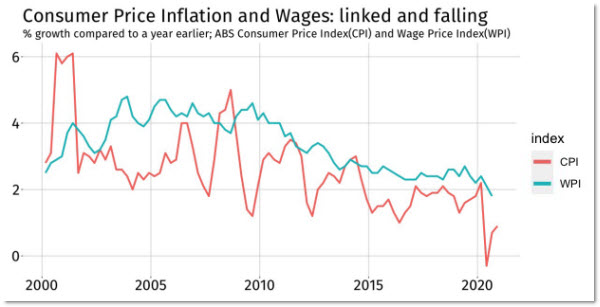

The immediate goal is to lift inflation, but the underlying goal is an improved labour market. Low unemployment and high wages growth generates widespread inflation. The reason the bank aims for inflation between 2% and 3% is that permitting higher inflation should let the labour market improve.

In one way this is a reason to celebrate. The lessons of the past 10 years have been learnt — consumer price inflation is not a risk right now. It really isn’t. On Wednesday Lowe pointed out that in other countries inflation hasn’t come about even when unemployment fell to record lows.

“Before the pandemic, when we had unemployment rates at 40- and 50-year lows in the US and the UK and actually even in New South Wales, we got an unemployment rate as low as it was in 1973. And even then wage growth was kind of two, two and a bit [percent], increasingly only very slowly,” he said.

“There’s some powerful structural factors at work, not only in Australia but globally … That means you have to have very tight labour markets and low unemployment rates to get wages increasing materially.”

This is good to hear. It means monetary policymaking authorities can learn! It might take a decade of slashing rates, but they can learn.

The last rate rise was in 2010. By the end of 2011 the RBA was retreating, having pulled policy too tight. It has now realised that to create wages growth, policy must be loose for a long time. Low interest rates create a vibrant economy that gets people into work.

But of course that’s not the only thing loose monetary policy does. It also drives up asset prices. The RBA wants this.

“Sustainable increases in asset prices support household balance sheets and encourage spending through positive wealth effects,” Lowe said. “Higher housing prices can also encourage additional residential construction.”

So far so good. But you have to be careful what you wish for. Interest rates at rock-bottom levels for four years make borrowing even cheaper. House prices could go berserk.

Crises always come from unexpected places. Are we planting the seeds of the next one in our recovery?

“Sustainable increases in asset prices support household balance sheets and encourage spending through positive wealth effects.”

Just. Crazy. Policy!

The idea that the economy will get back on track provided that house prices continue to go up, based on an untestable theory of ‘positive wealth effects’ is the very definition of unsustainable.

And how can even minuscule asset price increases that add tens of thousands of dollars be sustainable when wages are not going up, at all.

And what of our heavily skewed asset markets, where basically buying a house or shares is seemingly the only option for investment, particularly when the RBA has, as deliberate policy, the intention of keeping bonds at record low rates.

This is market intervention gone mad. Generally I’m all for market intervention, but we have our major federal regulator blowing hot air into the existing bubbles of houses and shares. Are they going to keep doing this forever? If not, and it should be a ‘not’, then this is by definition unsustainable.

On recent months, the housing market is looking at 10% to 15% asset inflation per annum, during a pandemic. I think we are being led by madmen. The crunch, when it comes, will be very bad indeed.

Agree, but one is very sceptical of the data, as are several statisticians, outside of the property agitprop, who have tried to make sense of it.

For example, ‘real value’ vs. the nominal/hedonic index numbers and indirect indicators, preferred by the sector and presented by media, everyday to people who mostly lack basic financial literacy…..

In real terms it appears that Sydney and Melbourne pre Covid were in fact stagnant for a couple of years, even in nominal terms, hence, decline in real terms?

Maybe now we are observing, helped by every stimuli possible, a gain making up the previous loss in value?

Finally, have we really seent he end of Covid economic impacts on e.g. employment etc.?

And in all this #JoshFromAccounts and the muppet government generally are mere passengers, or worse, bystanders. No policy, no vision. Just an idiot neo-liberal delusion that markets are all good. We have a complete vacuum as the federal government and they are still 50/50 in the polls. How dumb are we?

‘ave a chat with some retailers Jason. If you are going to reproduce the views of Lowe the characteristics of the economic environment need to be take in account too.

Just this week a premier has locked down a major city for five days. Forecasts as to inflation (or rather the absence of it) are to be applied to current and forecast spending patterns for consumer goods and for assets (two distinct entities) – taking into account debt as a whole. This point could be extended for some thousands of words.

On the other hand : you are writing for Cky after all.

“Higher housing prices can also encourage additional residential construction.”

In who’s universe is this actually true? We’ve had outrageously high house prices for decades and we’re hundreds of thousands of dwellings short of market demand. I heard the median house price in Sydney is now over $1M. In a country as vast as ours this is obscene.

Murphy comes across as a neo-Freidman-ite. The opinions for people are tents, caravans or houses. It is a function of population growth and regional development. Fly in and out has been deleterious for regional Australia.

As an aside, there is not theory of Friedman’s that is still standing.

It is though Australia and its economy has not changed for generations with focus upon digging stuff out of the ground, growing stuff or building houses? Meanwhile ignoring innovative and sustainable industries in health/medical and environment e.g. solar.

Property stimulus and activity can have a broader effect on the economic activity on the way up but what happens if it ‘overshoots’ and then followed by precipitous decline?

Although not featured (ever) in media and related narratives, there has been a significant drop in short to long term temporary resident ‘churn over’ (via the NOM) who are ‘net financial (budget) contributors’ and renters, which will take some years to regain similar numbers or position.

This in turn is backgrounded by an ageing declining permanent population base which will hit the wall in five years as retirement/downsizing (has started) and the ‘big die off’ of baby boomers commences; some analysis links flat per capita economic activity with increasing numbers of retirees (frugal and/or do not need to buy much vs. media’ favourite demographer claiming ‘immigrants’ are to blame…..).

This is the end of medium/large families, to be followed by more balanced or smoothed out demographics which will impact the property market mantra of ‘immigration’, ‘population growth’ and ‘prices always go up’.

Take a look at marriage rates over the last half century. The median rate for females (cf fertility) declined below 22 years from 1955 and did not recover until 1980. Currently, it is about 28 years. Then take a look at single dwellings.