For most of its time in government since 2013, the Coalition has been keen to cut company taxes. Malcolm Turnbull and his then-treasurer Scott Morrison devoted great effort to trying to secure passage of tax cuts for large corporations that would cost the best part of $100 billion in lost revenue.

A core part of their argument was that Australia was being left behind by other countries lowering their corporate tax rates, rendering us “uncompetitive”. Cutting company taxes would be an economic panacea, we were told. It would boost investment, productivity and employment and even wages growth with grateful corporations passing on big pay rises to workers in a splendid demonstration of trickle-down economics.

Donald Trump’s company tax cuts in the US reinforced the argument from the Coalition, business groups, and their media cheerleaders here that we urgently needed to make our corporate tax system more “competitive”.

“Our current uncompetitive business tax rate will make it harder for Australian businesses to continue to attract the investment,” Morrison warned in 2017, unveiling company tax cuts.

“Our tax system is becoming uncompetitive and … we risk becoming stranded internationally,” he insisted. “At 30% Australia’s company tax rate remains one of the highest in the world and significantly above the OECD average,” he said, adding “if we don’t act, we risk our businesses becoming vastly uncompetitive”.

Our tax system was uncompetitive, he argued in 2018. “It must not leave them uncompetitive in a global marketplace that embraced lower company tax rates long ago.”

Fortunately, the push by the Coalition’s biggest donors to cut company taxes was defeated. Meanwhile, evidence was building that the Trump tax cuts hadn’t increased investment or wages, but merely added to the Republicans’ massive deficit and rewarded shareholders and corporate executives.

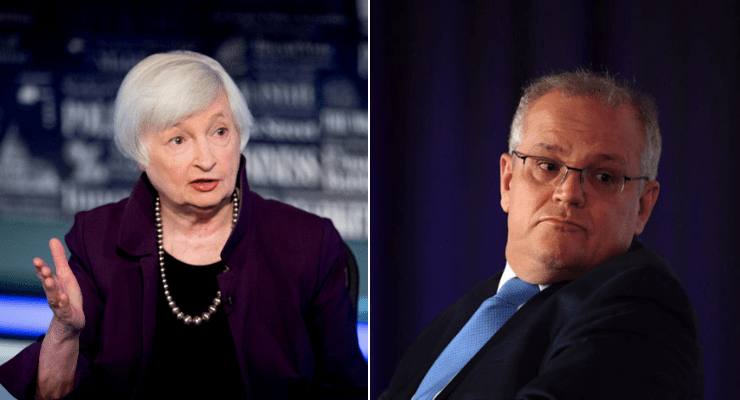

Now the Biden administration proposes to reverse Trump’s company tax cut, and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen wants to return the US to good faith international discussions about a global minimum company tax rate to curb multinational tax avoidance — a process that the US under both Trump and Obama had either failed to press forward or actively undermined.

The international tax environment is now about avoiding a “race to the bottom” and governments with massive post-pandemic deficits looking for sources of revenue to start the process of balancing their budgets. The International Monetary Fund, once the high priest of neoliberalism, now strongly supports more effective international taxation of corporations.

That’s left Morrison in an uncomfortable position. Asked yesterday about Yellen’s proposal, Morrison was singing a different tune to a couple of years ago: “I think you will find, would see Australia in a lot more competitive position than you would give Australia credit for … Australia’s overall system is proving to be incredibly competitive and a lot more competitive than that analysis would suggest.”

Perhaps Morrison was making a subtle point about the fact that many of our biggest companies still pay little or no tax at all. News Corp, for example, continues to rip off Australians to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars a year in avoided tax. So too do big fossil fuel companies.

Credit where it’s due: as then-treasurer, Joe Hockey tightened up some of the worst features of the tax system that allowed multinationals, and especially big tech companies, to dodge tax altogether. But it’s only thanks to Labor’s initiative of greater transparency around corporate tax returns that we have been able to see the true extent to which big companies still treat the Australian tax system as partly voluntary.

If the government is keen to start repairing the massive budget deficit it racked up, and our tax system is now highly “competitive” as Scott Morrison claims, then there should be room for Australia to lift its tax take from the biggest companies. Unfortunately, those companies include many of the Coalition’s biggest donors. But it’s one sure way to get the deficit down that would actually be popular with voters.

When is a Financial Transaction Tax getting a mention? Tax wealth creation at the source.

I recommend everyone reading Michael West Media to understand just how little lots of our major companies avoid paying any tax any many pay token amounts. I recently read that their was a idea that we should tax these companies basis on their turnover so they could not avoid as they must declare these figures for the stock market. I am sure if the Opposition went to the electorate with a proposal to have a Royal Commission with a view to have a tax system that is fair to all such a matter would be endorsed by the electorate

I second checking in with Michael West Media, they do solid work on this front. But as for tax justice at the polls i’m not as optimistic.

Fair dinkum tax policy has been cancelled by Fake Murdoch News Corpse whenever presented to the voters at election time.

And unless we get media momentum around bringing LAW AND ORDER to the wild west that is tax law in Austalia then Murdoch and his Band of Corporate Cronies will ride off into the sunset again… AT OUR EXPENSE.

Yeah good luck with getting Labor to do what needs to be done on so many fronts. Promise of action on climate, taxes and social housing would easily get them elected, yet they didn’t do it last election and I don’t see any signs of a build up in that direction for the next election.

AA & his controllers have specifically excluded reforms of negative gearing, franking credits and fossil foolery from “Labor” policy.

Why vote for LNP-lite?

Sorry, the AWAITENINGED madBot has pounced.

The best metaphor for the ‘trickle down’ theory of wealth making its way from the richest CEO to the poorest workers, is that of the Human Centipede. Do I need to elaborate?

They won’t rise to the occasion.

Beware of moral hazard of an imported or confected libertarian issue that gives advantage to global and/or multinational corporates, based upon spurious evidence of global but limited tax comparisons, or false equivalence.

Elsewhere may have lower corporate taxes, but may have significantly higher employment costs e.g. high social security contributions, local and other taxes also (but n/a in Oz more streamlined or efficient).

However, shell companies (vehicles linked to corporate entities) employing nobody, but moving millions or billions round from one national jurisdiction to another, can make significant gains by even a fraction of a percent decrease in corporate tax.

Brexit was an issue for the same and Russians oligarchs etc. too (exemplified by donations to the Tories); also an opportunity for hedge funds, but local businesses behind borders, negligible.