If you didn’t already believe it, here’s more evidence the lockdowns were worth it. Emerging research is giving Australia’s COVID-19 elimination strategy an enormous tick of approval.

We know COVID-19 has had a fatality rate of 3% in the Australian context (909 deaths from 29,304 cases). That has robbed many people of years of life. But new evidence suggests the fatality rate only begins to measure the impact of the pandemic on Aussies’ health.

We’re talking about “long COVID”. Researchers from St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney have been tracking patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19, and they have chilling news about the course of the illness.

The stats

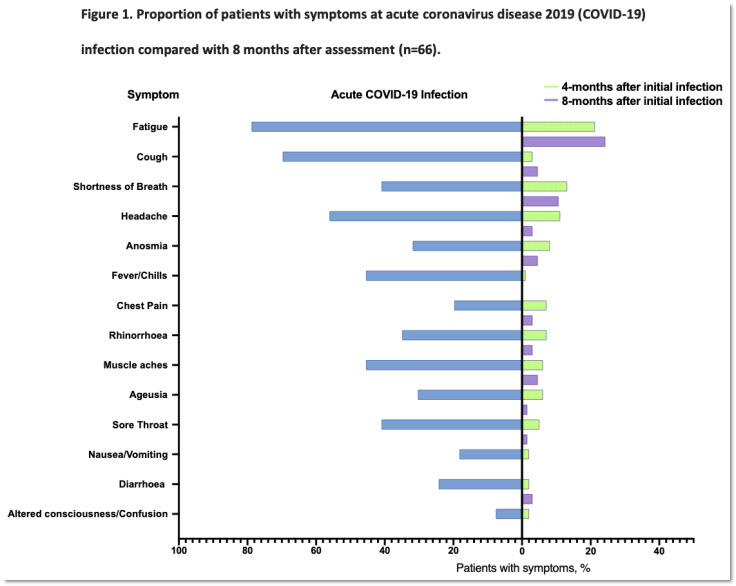

Of 99 patients diagnosed by April 28, 2020 and followed since, 19% met the criteria for long COVID at 240 days post-diagnosis. As the below chart shows, many symptoms are ongoing, but fatigue is the most common problem for people who’ve had the virus.

Long COVID hits women more often than men, affects the young and the old, and while it’s more common in those who had severe symptoms in the acute stage, it can also afflict people who had only a mild course of COVID-19. The 19% estimate of the burden of long COVID excludes lots of patients who weren’t diagnosed directly at St Vincent’s and counts only some symptoms. The researchers describe the figure as “conservative”.

The implication of the research — which at this stage is a pre-print that’s yet to be peer-reviewed — is that from the 29,000 cases of acute COVID-19 in Australia, there would flow around 6000 cases of long COVID. Most of them will be in Melbourne, where the Victorian second wave hit more than 10,000 people in July and August. Those people are not as far through their course of illness as the Sydney cohort, and the study has bad news for them about the chances of improvement in coming months.

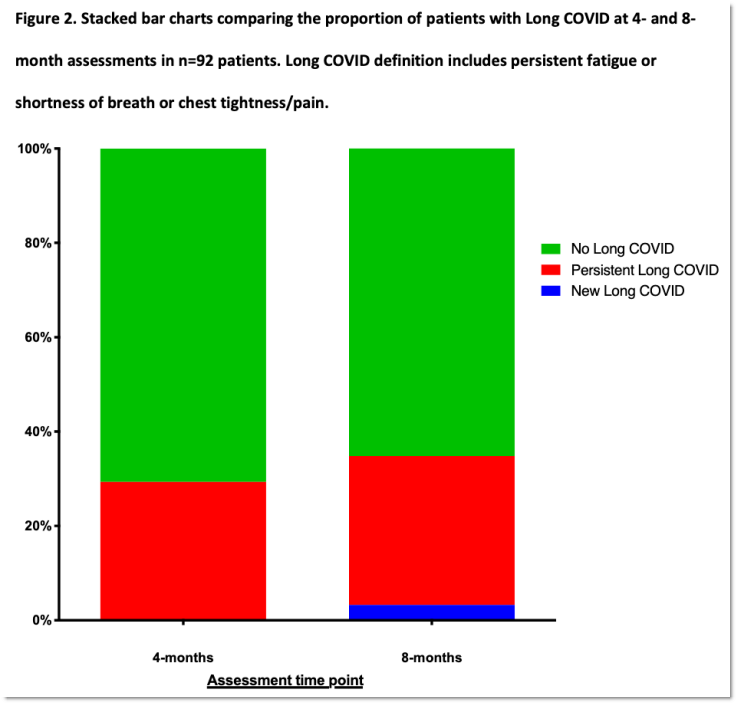

The researchers tracked long COVID patients over time and hoped symptoms would begin to resolve. Nope.

“There was no significant improvement in symptoms or measures of health-related quality of life between four- and eight-month assessments,” the researchers said in their paper.

“A considerable proportion (around 20% ) of the total cohort did not feel confident returning to pre-COVID work, had not returned to usual activities of daily living or had not returned to normal exercise level.”

As the next chart shows, there was no statistically significant change in the rate of long COVID between four-month follow-up and eight-month follow-up.

The researchers suggest the long COVID group has two subsets: people with damage to the heart and lungs from the virus; and people with fatigue and “brain fog”, whose illness is more akin to ME/CFS (chronic fatigue syndrome).

German researchers also found that around half the patients they assessed for long COVID met the criteria for ME/CFS. That’s potentially bad news, as ME/CFS can last a very long time and has no cure. It is not well-understood and research into it is poorly-funded.

The impact

What’s excellent about this paper is it is prospective. They selected the patient population before they got long COVID, and followed them afterwards to see what happened. All the people were diagnosed with COVID-19. This is a much more rigorous approach than many other papers, where the patient populations are selected after they got long COVID, and don’t all have COVID-19 diagnoses.

Why don’t the people with long COVID all have COVID-19 diagnoses? There’re a lot of people with long COVID in the US and UK who got it in those early waves when they weren’t testing. They have the experience of long COVID, but lack evidence of ever having had COVID-19. That leaves the door open for commentators to deny they ever had COVID-19, and therefore to psychologise their subsequent experience of long COVID.

A widely shared article in The Wall Street Journal in March took this approach, arguing: “Such symptoms can also be psychologically generated … Long COVID is largely an invention of vocal patient activist groups.”

The temptation to attribute to psychology that which medicine is yet unable to explain is huge. But why are people so attracted to the idea chronic illness is explained by rampant hypochondria?

Perhaps it has its origins in caveman society. Being sick was really bad for the collective so, to dissuade anyone from being sick, it was strongly socially punished. But these days, being chronically ill is mostly bad for the person who is ill. If you can barely leave your home, you’re probably poor and unable to participate in the good things society can offer. Perhaps you qualify for disability support pension, but you must repeatedly fight Centrelink for it.

The supposed upside of “imagining yourself” into chronic illness just isn’t there. Nevertheless, the idea chronic physical health symptoms represent some deep Freudian impulse won’t go away. Perhaps this is a manifestation of the “just world fallacy”, the idea that bad things happen only to bad people. It’s likely comforting to think that if people are desperately sick their whole life, it’s because, at some level, they want to be.

That’s why proper medical research into these post-infectious illnesses is so important.

(If anything, people are hyper-chondriac, not hypo-. In the Australian study, 54% of the people who qualified as having long COVID based on their reported symptoms nevertheless said they had recovered!)

These researchers will follow the patients for two years at least. But hopefully this will be the last prospective trial in Australia, because we just won’t have enough patients. The population of people who have had COVID-19 is mercifully low by international standards, and most people contracted it prior to the widespread recognition that long COVID is a real risk, so we can’t start new prospective studies.

Lockdowns, mask rules and border closures have meant fewer than 1000 new COVID-19 cases so far in 2021. They may also be saving us from a huge wave of long COVID sufferers who would be sick for years — or indeed for the rest of their lives.

“Lockdowns, mask rules and border closures have meant fewer than 1000 new COVID-19 cases so far in 2021. They may also be saving us from a huge wave of long COVID sufferers who would be sick for years — or indeed for the rest of their lives.”

For a non medical journalist this is a well argued article about medical issues and consequences.

ME/CFS has been described as being like having cancer except you don’t die. Anyone close to someone afflicted with it will be aware of the agony, despair and shame it causes. If there is one possible silver lining to this depressing cloud, it is that perhaps now these ill-defined and poorly understood conditions might receive the clinical research effort necessary for a proper understanding and effective treatment.

Now Jason’s comment really scares me. The possibility of a life that offers un-ending limitations viz-a-viz infection – death, not to be dismissed. Mr Prime Minister get your act together . . NOW!

True Jason, and this was becoming clear in middle and late last year. The ‘let her rip’ crowd have been wrong every time on multiple facets. Most particularly the awe inspiring levels of stupidity that suggested that locking down was a greater cost than letting rip. They were wrong beforehand, during and in retrospect.

Being wrongedy wrongly wrong has never been a problem for this specific cohort – the ones who regard the community as their personal ATMs and resources to be harvested.

Why would they care if large numbers die or suffer, not as if there is any shortage.

Long COVID is CFS/ME. Which is an extended mammalian sickness response. None of this is difficult to explain. Treatment is not easy in the real world though