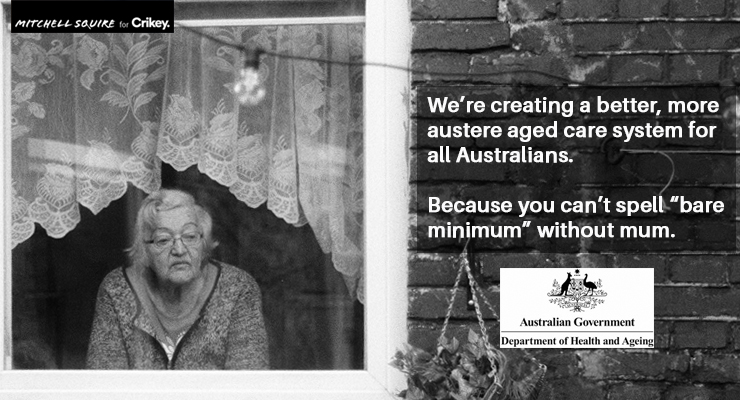

The government’s anticipated spending announcement about aged care in next month’s budget looks to be well short of what is needed to deliver the changes identified as necessary by the aged care royal commission.

In what looked like an actual scoop rather than a traditional budget drop, Nine’s James Massola reported at the weekend a plan to increase aged care funding by $10 billion over four years. But how small $2.5 billion a year is in the face of the sector’s problems was demonstrated by a report from the Grattan Institute yesterday.

Stephen Duckett and his colleagues accepted the figure put forward by the royal commissioners that aged care was $9.8 billion a year worse off than it should have been because of funding cuts by successive governments, and argued for that funding to be restored.

That would allow the home care package backlog to be cleared, home care services to keep people out of residential care as long as possible to be upgraded, the workforce to be increased by 70,000 people to establish minimum levels of care in residential facilities, and a network of “care finders” to be established to help seniors navigate the system.

That reflects the report’s emphasis on delivering on the royal commissioners’ goal of a rights-based system and commissioner Lynelle Briggs’ recommendation for “care finders”, which Duckett and co say “is absolutely fundamental in ensuring a rights-based system”.

Care finders should provide face-to-face help to older Australians as they try to navigate the aged care system. They should be agents or independent advocates for older people, not for government. They should train older Australians and their families in what human rights means for their care … [They] should be qualified, independent from service providers, and locally based in a regional organisation rather than operating out of a distant centralised body … [They] must have some level of independence, employed by independent regional organisations.

The report also urges that aged care workforce training includes a substantial component of competencies in human rights. This re-foundation of aged care on a rights-based philosophy is the crucial test of the government’s response since so much else in the royal commission report flows from that.

A failure to properly centre the system on individual rights, even with a substantial increase in funding, would perpetuate existing problems and the historical approach of recent decades: seeing quality aged care as a service to be rationed out with an eye to balancing fiscal restraint with political imperatives, rather than a basic right to which seniors are entitled.

Such fundamental changes, and such massive funding increases, are required because aged care is a policy tragedy created by successive governments and generations of policymakers at the political and bureaucratic level — all reflecting an indifference to senior’s needs.

It should demonstrate to both decision makers and voters what can happen to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) if the same mentality of cost minimisation is allowed to dictate the fundamentals of the system.

If the NDIS is being run with an emphasis on avoiding cost overruns — with a unit within the National Disability Insurance Agency operating under a former McKinsey consultant to slash costs, prevent growth in participant numbers and impose “sustainability” rather than being founded on the rights of disabled Australians to receive quality care — it means disability services will track the same institutional path that aged care has over recent decades.

That means underfunding, poor governance and, inevitably, occasional political firestorms prompting short-term fixes, along with the rights of clients and carers being sidelined.

These will inevitably end up being addressed in the disability care royal commission of 2034, with similar recommendations to similar problems that the government must deal with in aged care in 2021.

The government has an opportunity for a fundamental overhaul of aged care. Prime Minister Scott Morrison isn’t responsible for what’s happened to aged care, but he has a blueprint to address it if he’s willing not merely to throw more money at the sector but to re-base the entire system — its funding, workforce planning and governance — around the rights of senior Australians.

Aged Care and any NDIS funded services should be run as not for profits. Much as I question the inequity of private schooling (a separate issue) tax payers money is translated into facilities for students, not siphoned off to profit shareholders and overpaid CEOs whilst vulnerable “clients” are victims of over zealous cost managers.

Every dollar of profit is money wasted.

Or, a some would see it, every dollar wasted on care is profit forgone.

I’ve got an idea….don’t give $9 billion to the aged care sector, which will be split $1 b for grandma and grandad toddling around on their wheelie walkers and $8b to the providers and their shareholders. Instead, train up independent inspectors who go into homes unannounced and inspect what is going on….short on food? dirty clothing? lack on medicines etc? Guess what you lose your old care facility and it is given to some authorised entity who is trained in all areas of suitable care and held suitably accountable. Save $8b and put it to good use somewhere else for older Australians.

I’m only 81 and I don’t want to be entrapped in one of the rubbish homes I see on TV.

That would help, but there needs to be enough funding for good care in the first place.

Perhaps if the law were to be changed to allow euthanasia as an alternative rather than the old peoples home.But that will not happen while they have a few years to as a cash cow in a private for profit home.

Or perhaps fund old peoples’ homes properly so people wouldn’t be faced with that choice?

Far too sensible an idea. You’re dealing with IPA/Liars politicians. Their only interest is making it easier for their donor mates to snap up Grandma and Grandpa’s house and add it to their swollen negatively geared rental property portfolio.

Same here at 81, too.

In my Mum’s , care facility, inspections were announced weeks in advance and those deemed cognitive enough to praise up the place and its staff were coached to do so.

When she first arrived, staff to resident ratio was quite high and made up of mostly middle-aged personnel.

Food was quite good and morale was reasonable (staff and residents) – but within 18 months everything changed.

Older staff whose pleas for better “anything” for residents resigned and were replaced by 18-22 year olds with little to no life experience, let alone experience with Dementia patients.

When I questioned management I was told it was cheaper to employ younger individuals and as necessary, agency staff from overseas, new to Australia.

It was the latter who showed the most empathy, whilst those directly hired were constantly heard stating that the residents were, “anally retentive” amongst other things!

Complaints fell on deaf ears but let me say that Sunday afternoons became the most concerning when the office door was locked to residents seeking attention while the lovely young things entertained the boyfriend with cheerful anecdotes of whichever resident they felt, deserved criticism and unbridled contempt and humiliation.

Around the same time, cuts were made to the diet of residents – with alternating days of soup and bread one night and party pies and sausage rolls the next, a meal the next then back to soup.

Residents were no longer taken outside the locked unit for walks in the garden as they couldn’t spare anyone to supervise. Instead, days, weeks, months were spent huddled in front of a television set, watching whatever program staff wanted to watch or listen to.

I could go on and on.

My mother was the one exception to the inside rule. I was in a position to make time to visit her every day and made it a mission to take her out for a walk (later a wheelchair, and in the week before her death, wheeled her entire bed outside) for fresh air.

I like to think that is the reason she was the only resident, never to succumb to the many gastroenteritis outbreaks each year.

Life for every resident in that particular Dementia Unit, was sheer hell, speaking as someone who saw what went on for almost four years.

Some of the myths and disinformation around aged care also need to be dispelled. Home care is okay for some, but for others it means continued imprisonment in a home they can no longer physically leave, care for or navigate. My wife and I regularly deliver meals to lonely people rattling around in family sized homes but with an adamant view they don’t want to be put ‘in one of those homes’. Not all aged care is ‘one of those homes’. The truth on what’s available, how they can be funded and what services they offer should be spoken of more, not just the lowest cost option of ‘home care’, which has its own set of issues. If we need more family homes for families, I’m sure any number are currently occupied by one or two elderly souls who are not making the most of what they own. We also need more conversations about ‘leaving something for the kids’. I told my mum (the last of my parents) that I wanted nothing and she should spend it on her needs. More options are needed, with truthful discourse.

“Not all aged care is ‘one of those homes’.”

But I suspect most are. We had a spray yesterday about the Greek run ones in Melbourne, where $tens of millions are being siphoned off.

How about we reconvene the RC and have them look at where the finding goes?

Of was that included in the one just finished but what was exposed is too politically damaging?

Adding the family home to means testing for the pension would result in older people being more willing to move to more suitable accommodation.

Meaning it is no longer a home but an asset. Please dont think going down this path is helpful. A home should be a home as long as we need it to be.

No, it’s both a home and an asset. Older people are sitting on huge windfall profits. Let them continue to live there if they choose, but not be subsidised by younger people who can’t afford to buy.

I would hate to see people on low incomes forced to sell their houses & get placed in gov run death traps. The LNP are not known for their empathy. Classing the family home as an asset will probably catch more poor house owners than wealthy ones who have many ways of hiding their assets. IF we had a fair & compassionate gov, I would agree with you. Sadly we have the LNP.

The govt run ones in Tasmania are mostly the best as they have mandated staffing levels at least.

They would be ACFs run by the state government as in other states. Private ACFs are former Commonwealth ACFs, funded and regulated by te Commonwealth government. However, the Rodent saw a way to make a quick buck and reward his donors at the same time by flogging them off to the highest bidder. The Commonwealth was to provide funding and regulate them.

However, Morrison cut $1.2bn from funding and has failed to regulate any of them, which explains the deplorable state of privately owned ACFs.

Of course owners are raking in huge profits allowing them to build $10m mansions and buy matching Maseratis.

The private sector needs cleaning up.

You still haven’t justified why an elderly person should be kicked out of the home they may have lived in for 50 years or longer.

Their house is their home, not a windfall profit to them. My mother lived in a hoiuse worth many times more than when my parents built it and she often speculated about whether she should sell and relocate.

I pointed out that the profit from the sale may not be enough to buy a house she’d like to live in. She loved her house and happily died in it.

Adding the family home to means testing is just another way to force older people out of their homes for the benefit of the negative gearing brigade. A house is not a money earner if it’s where you live.Owning a house costs money and people should be allowed to stay in their homes as long as they like.

The only reason the IPA/Liars are so keen to kick older Australians out of their homes is to satisfy their negative gearing donors.

Not all elderly people own their own homes, and quite often, “choice” does not factor in to the equation of where a loved one is accepted in out of home “care” – and I use that term loosely.

In my late Mum’s case, albeit 10 years since her death in a “care facility”, it was a lengthy process after her hospital admission for Alzheimer’s (diagnosis after various tests), whereby a Social Worker hounded me several times a day to get her out of hospital.

The fact that I’d visited 9-10 places within an hour’s drive of my home, in various directions, and put her name on a lengthy list did not matter.

At each place I was told I had to wait for someone to die before Mum would be accepted and even then there were no guarantees because the waiting list was so long with others in the same situation.

In fact, five years after her death I was still receiving calls from facilities saying that they now had a vacancy.

This meant in effect, that a vacancy had arisen almost 9 years after I’d initially made contact with them, which shows how long the waitlist was.

Of course, in Mum’s case as in many hundreds, if not thousands of others, she had no home to sell and was on a War Widow pension, which I was told made it much harder to get placement.

I was advised by the Social Workers to accept the first placement I received, so they could “have the bed” – and that’s what I did.

It was a privately owned facility who accepted Mum because they said, they were required, by Government, to accept a number of Service pensioners per year.

And let me just say that it was the absolute worst decision, in every way, that I ever made, in accepting the first placement offered.

Great observations.

NDIS, Aged Care, Health, Education, Climate Change…. will never be important issues for the LNP unless the bulk of funding flows directly into the cavernous pockets of big business and LNP’s financial funders. Outright rorting is a little more problematic only because there is higher possibility the rorting hands of LNP apparatchiki at large can be detectable.

Quality of care, education, environmental sustainability etc. will, as already evidenced during periods of LNP federal government, be unintended but nevertheless a useful excuse/channel for partisan graft and corruption.

On the other side of the coin (from those rightly concerned about profiteering), in terms of positive impact on the economy, money spent paying lots of people at the lower end of the socio-economic scale to deliver services is one of the most productive least inflationary ways of investing government money.