The “pink tide” of leftist governments turned in South America years ago with the jailing of Lula in Brazil, the defeat of the Kirchners in Argentina, the double-cross of Rafael Correa in Ecuador by the right wing of his own party and, in 2019, Bolivia’s coup against the Morales government.

For a while it looked like the old guard was back, running the joint for the shadowy old wealth with the blessing and connivance of the United States.

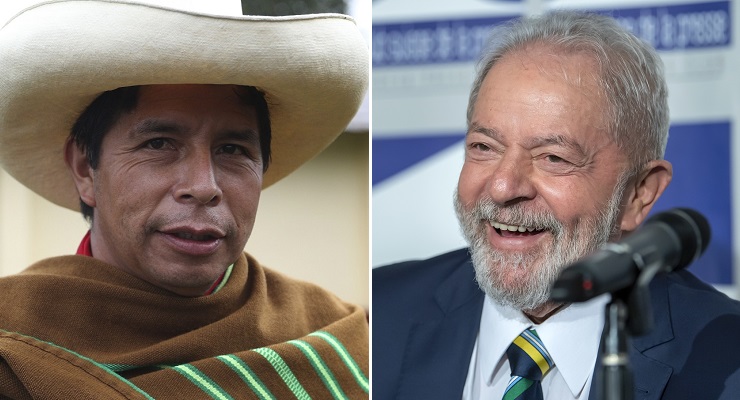

Now it appears to be turning back, faster than most of us dared hope, becoming a pink wave. In Brazil, Lula — former leader of the Workers’ Party — has been freed from prison after his conviction and imprisonment for corruption was shown to be itself corrupt (much of it exposed by the journalist Glenn Greenwald), and right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro’s handling of COVID-19 went from disastrous to catastrophic for the country.

In Argentina, the left was back after a single term from the right. In Bolivia, the elections following the coup against Evo Morales’ Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) party resulted in its re-election. Now, coup leader Jeanine Anez is herself under arrest. In Ecuador, though right-wing candidate Guillermo Lasso has won the presidency, indigenous party Pachakutik became the second largest party. And Venezuela? We’ll get to that.

But the most interesting contest of all is in Peru, where this year’s general elections look set to become a contest between a self-described “communist” and a free marketeer. In the counting of votes in the first round of a two-round run-off contest, teachers’ union figure Pedro Castillo has won the first round of the presidential election, albeit with only 19% of the vote, among a field of 15 candidates.

Appearances can be deceptive however, for the next three candidates were of the right: centre-right neoliberal Hernando de Soto; far-right candidate Rafael Aliaga; and Keiko Fujimori, second-place-getter on 13.4%. Fujimori, the daughter of former president Alberto Fujimori, is likely to be Castillo’s biggest challenger. She is widely loathed outside a certain circle, and her accession to the second round makes Castillo’s victory more likely.

The right-wing trio are all interconnected. Aliaga has described himself as the “Peruvian Bolsonaro”, and was previously a Fujimori supporter. De Soto has been Fujimori’s adviser.

All are also tainted by a scandal connected with the Brazilian “Odebrecht” firm. The proliferation of candidates appears to be a tactic by the right akin to a shell-game, to disguise the substantial unity of a reactionary elite. The three candidates below the first four are all of the left, which gives the left another 25% to join Castillo’s 19%. The right trio filed about 35% collectively.

That Castillo can describe himself as a “communist” (in the general sense, not in a Lenin-Stalin-Mao sense — which in parts of South America counts as names for triplets) and surge to the top of the left, is a measure of the shift to a new era. It’s one not overshadowed by the memory of the ruthlessly violent “Shining Path” movement which emerged from the Andes in the late 1970s and worked to stage a Maoist peasant revolution.

The Shining Path’s campaign of terror (it was led by a teacher too; be glad that all we get are wars over phonics) pushed Peru into the arms of the right — specifically Fujimori Sr. Fujimori defeated the Shining Path, but only by letting the army commit atrocities against Andean villages in order to deprive the Maoists of active support — a strategy which quickly turned into mayhem with a racist edge. Also corrupt, Fujimori fled to Japan ahead of prosecution.

The complex electoral system was designed in part to prevent a repeat of Fujimori’s gathering of quasi-dictatorial power. The predictable result has been political horse-trading, stagnation and lack of leadership. The support for Castillo is a sign that people have had enough, not only of the right but of centre-leftists, who immediately tilt towards neoliberalism as soon as elected.

Castillo’s supporters want a government much like that of Morales and Vice-President Garcia Linera (a Marxist sociologist and former guerrilla) in Bolivia, which has done extraordinary things in the reduction of absolute poverty, the extension of substantial indigenous rights and walked a tight line between development of resources (by publicly owned utilities) and environmental protection.

The turn back to these movements probably represents an aspect of one of the most important things happening in the world today. That’s the defeat and discrediting of the classical liberal-social conservative ideology sparked by Thatcherism and Reaganism and carried to new heights first by post-1989 globalisation, and then by post-9/11 consolidation of Western national security states.

Neoliberalism has continued as a process, of course, but the suggestion that it offers some sort of human liberation has gone.

In the 1980s and 1990s, following the collapse of the global socialist movement, the neolib-neocon right could project their policies as an expression of human nature, rising from the waves. That’s gone now. The right has driven the global downward drift of wages, the financialisation of the world economy and a series of decades-long, multi-trillion-dollar wars. They have resorted to a cod-populism, which, in the home of cod-populism, appears to have been exposed more rapidly than elsewhere in the non-Latin West.

The paradox in all this is that, whatever model such pink governments pursue, the Venezuela model isn’t one of them. But that sad tragedy is both a product of what was required to break through in that country — a quasi-military campaign against a particularly vicious establishment which had murdered hundreds of protestors in the early 1990s — and the reason for the establishment’s viciousness, the oil.

Oil corrupted a Chavismo movement that had already developed into a mini-cult of personality, mirroring the junta-style politics it opposed. Correa, Morales and others have avoided that, though every minor transgression has them lumped in with Ugo and Maduro.

Castillo will have a hard road to the presidency in the second round. The centre-right would pile in behind any populist who gets onto the run-off ballot. The sharpness of the contest shows both how divided South America is and how militant.

The question worth asking: is it still struggling out of a brutal class war past, or is a perpetually counter-cyclical region a taste of the future from a system whose politics is devoid of the multiple release valves which constitute Anglo-American democracy?

Viva the pink wave! As every article about Latin-world politics is required to end with.

Excellent article. Every one of those S.American countries have been under attack by the CIA on behalf of the War Mongering USA Govt. Their leaders have been assinated & the most horrible Right wing Govys installed –All to allow the USA Mega Companie to rape & pillage their assets without protest.

Sooner the USA is brought to its Knees the better for mankind. The sooner Australia gets out of being part of 5 Eyes the better for Australians.

“Cod-populism”? Sent me on a google adventure with that one!

still unable to sort this one out. Any clues?

I think it means fake populism. Though by no means certain.

Me too, Mercurial. Something new to be learned everyday.

What are the multiple release valves that Anglosphere democracies have that Latin American ones don’t? Better imperialism?

Identity politics would obviously be one.

A well-functioning bureaucracy and judicial system that gives the impression of being open to participation by all, and open to change by all (or most).

There’s a big long list, that doesn’t change the underlying character of our democracy.

Thanks Guy for giving an update on an arena that anglosphere navel gazing rarely reaches – and reporting actual events rather than opinionated outrage of one kind or another. From my limited reading on South America I recall that it’s where US and anglo politial scientists like Huntington and Williamson created the idea of ‘failed states’ and solutions like the Washington Consensus – austerity, privatisation, deregulation of labour markets and currency controls. And gee, who was there to restructure the debt, buy the privatise companies etc etc? Wall St and the City maybe?

But out of ‘failed states’ others like Douglas North developed the whole idea that institutions were more important than markets for economic prosperity. Democratic parliaments, an honest judiciary, apolitical army and police, good public education and health, an honest banking system and stock market. Hopefully the pink wave can break the cycle of reactionary-revolutionary politics by building real institutions that are strong enough to resist the attempts of the rich and powerful to take back control.

For anyone interested at all in the above meanderings, I should have mentioned that Daron Acemoglu is highly recommended reading

We could learn a thing or two from it.

It was sweet reading when the jailed coup leaders in Bolivia are now screaming political repression.