How is female employment going? The recession has turned Australia’s eyes to gender differences in the labour force.

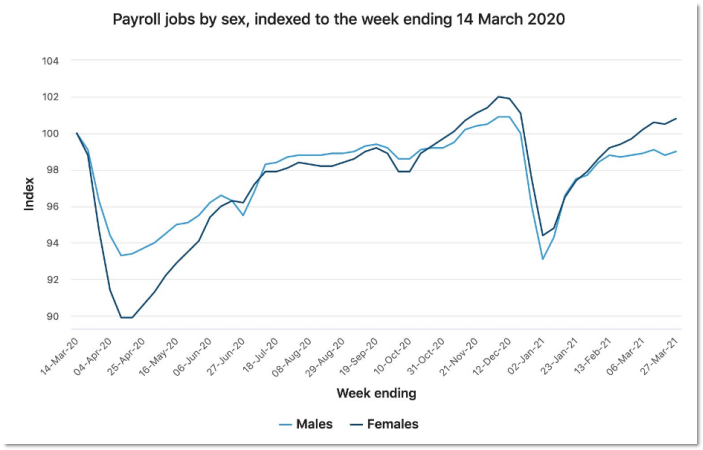

Early commentary was about how women were losing jobs faster than men. But since the jobs recovery women are gaining jobs back fast, as the next chart shows. Female employment is now higher than it was at the start of the pandemic.

The fast decline in women’s employment is related to the fast recovery, and why the fast recovery is not quite the simple good news story it appears.

As the chart shows, female employment has been highly volatile during the turbulence of the past 13 months, while male employment has been more steady by comparison.

What’s going on here? Well, women are far more likely to be employed part-time and as casuals. As the Australian Bureau of Statistics says: “Casual workers accounted for around two-thirds of people who lost a job early in the COVID-19 period.”

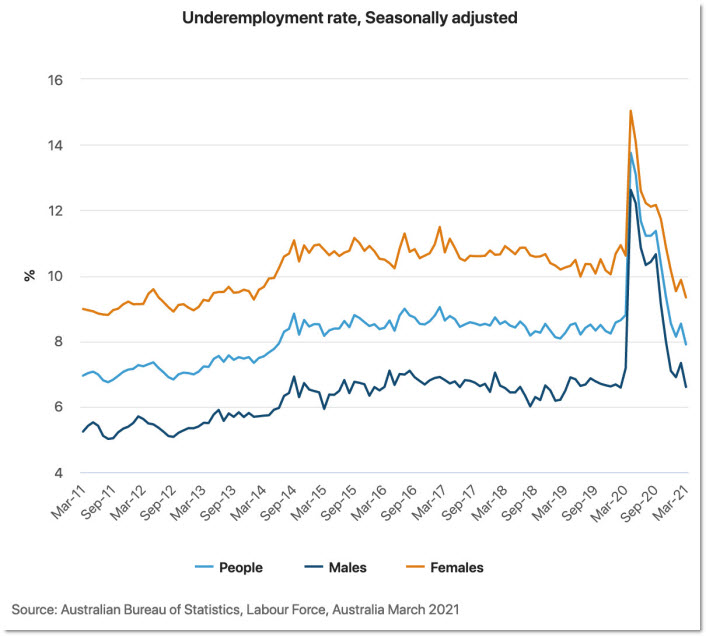

Women’s work characteristics mean they are far more likely to be underemployed, wanting more hours. As the next chart shows, women have faced underemployment rates almost double those of men over the past decade.

Underemployment drifted up over the past 10 years and hasn’t improved much since 2016, despite reductions in unemployment. They say the future is already here — it’s just not evenly distributed yet. That’s definitely true in the labour market. Women work in a casualised, insecure labour force that men will also face soon.

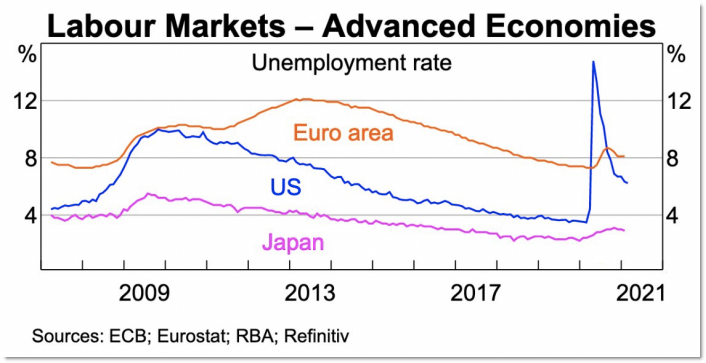

Essentially, women in Australia work in a much more American-style labour force, with less certainty, less power and more insecurity. The pattern we see in Australia is similar to that of unemployment overall in America: when the pandemic hit, workers were swiftly thrown on the street, but as the virus came under control they were rehired in huge numbers.

You can see this in the next chart: America’s labour force is highly dynamic. An awful place to be in bad times, but also a better place to be in good times. The contrast with Europe is marked. Its labour markets feature more full-time work and stronger labour protections, the sort of conditions that tend to be enjoyed by men in Australia.

Which model is better? The US is much richer than Europe and has had lower unemployment for many years. But the bottom end of the distribution does worse in America than in Europe, especially in bad times.

America invented the idea of the “working poor”. Its flexible labour markets are good for many, but not for all. The same is apparently true for women who work in Australia. For some the flexibility is a blessing. But many can’t get the hours they want and suffer when the economy turns down.

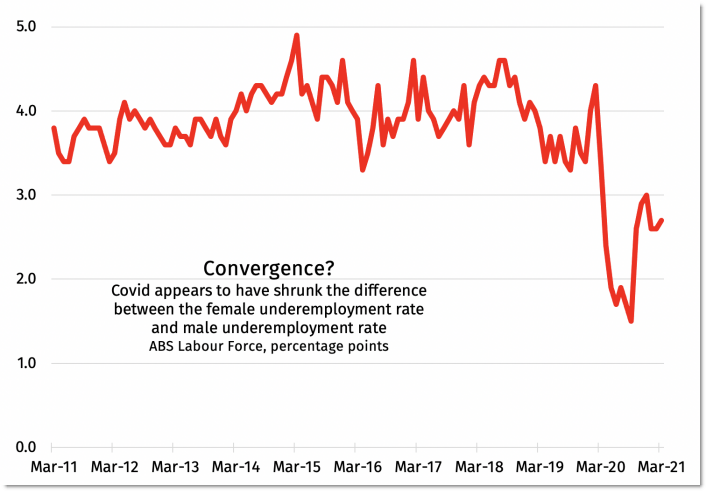

There’s an intriguing wrinkle in the narrative here. If you look back up at the graph of male v female underemployment, there’s an interesting phenomenon in the past 12 months or so. The gap between male and female has narrowed. Male underemployment spiked very high and hasn’t fallen below its earlier level; female underemployment spiked before dropping to below pre-pandemic levels.

The difference between male and female underemployment is shown in the next chart, and it raises the question of whether a great convergence is happening. After all, female labour force participation is rising. Could it be the case that men and women will face similar levels of underemployment in future? And if so, will that be a sign of improving conditions for women in the workforce, or deteriorating conditions for men?

I really don’t understand the political acceptability of the concept of “working poor”. As much as I disagree with it, I can at least comprehend why so many hate welfare provisions that keep people out of poverty. But those that work aren’t “free riders”, so why is a basic standard of employment not more politically pressing? It’s almost as though people want there to be those in poverty, even if the moral justification for it that usually accompanies anti-welfare screeds didn’t apply.

Yes, “almost as though people want there to be those in poverty” – that was the point of the Rodent’s SerfChoices.

He was hot for the US idea of insecurity which he lauded as job flexibility – imagine how that would have helped the GFC.

And who did most to ensure the fragility of the amerikan working poor, always a paycheck away from penury?

Bubba Clinton, at the urging of Killary, during his 2nd term when he was no longer beholden to the repugs for re-election.

Just as HawKeating – a decade earlier – with the mendaciously named Accord destroyed the power of unions to protect workers .

UBI. NOW!