Good Lord, the religious right had some bad press lately. Most recently it was due to the federal government’s infamous “consent” videos. Not only were they cringeworthy, problematic and enormously expensive (as Amber Schultz reported in Crikey on Thursday), the sex-ed resource was produced by an organisation with possible links to a US-based conservative religious think tank, and it hosted a video and study guide featuring “blatant victim-blaming rhetoric” from another Mormon organisation.

The inclusion of untrained religious groups against expert advice echoed the Coalition’s couples counselling foray in the domestic violence space. Morrison also continues to cop criticism from Australian of the Year Grace Tame and others for promoting Amanda Stoker to assistant minister for women. Stoker is a hard-right Christian who controversially defended a “fake rape on campus” speaking tour and the awarding of an Australia Day honour to its leader Bettina Arndt.

Arndt has previously interviewed Tame’s own alleged abuser, during which Tame claims they “defended crimes against children including rape and child pornography”.

The Morrison government is reportedly looking to win back the trust of women with a more female-friendly budget and a national summit on family violence. But the influence of its conservative Christian wing, to which Morrison belongs, and their continued regression on gender politics is hampering such efforts, drawing fewer allusions to the CWA than to, say, The Handmaid’s Tale.

The relevance delusion

Right when the influence of religion on public life is ripe for renewed scrutiny, prominent atheists look just as backward as the Bible bashers.

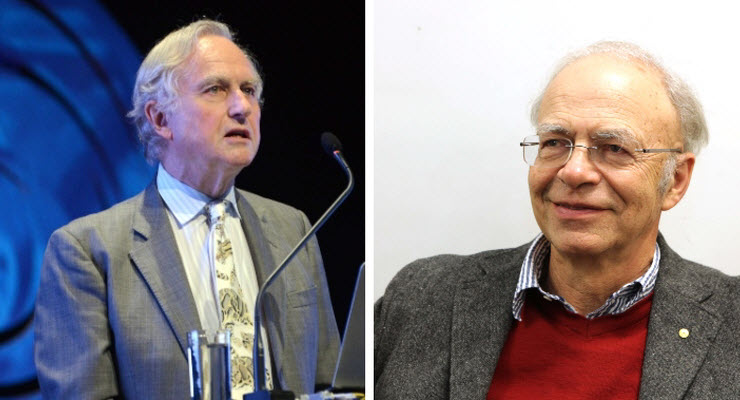

Richard Dawkins was last week stripped of a prestigious humanist award for offensive remarks about transgender people. The American Humanist Association said the author of The God Delusion had “accumulated a history of making statements that use the guise of scientific discourse to demean marginalised groups”.

Meanwhile, proudly godless Australian philosopher Peter Singer last week launched a new Journal of Controversial Ideas to rapturous applause from The Australian, promoting the dubious narrative that academia has been ruined by left-wing “cancel culture”.

So threatened by the baying mob are the precious professors, the journal will allow them to publish anonymously. Pseudonymity has legitimate pros and cons, but Singer’s example of shielding a feminist professor from backlash against her anti-trans writing would, as Deakin philosopher Patrick Stokes wrote, merely provide “a safe-house for ideas that couldn’t withstand moral scrutiny”.

The New Atheists are getting old

These are merely the latest in a string of disappointments from the New Atheists, the obnoxious non-believers who came to prominence in the early 2000s. Their demise is lamented particularly by those of us influenced by them.

At 12 years old, I stopped believing in God after watching Christopher Hitchens videos on YouTube. I had once played Joseph in the church nativity play. But watching the “four horsemen” dissect the pompous magniloquence of Biblical rhetoric, I found their logic irrefutable and their charisma intoxicating. From then on, I was an atheist.

Yet these public intellectuals soured with age, especially since the Iraq War turned their focus to increasingly hateful denunciations of Islam. As Jeff Sparrow wrote, they revealed themselves to be “toxic know-it-alls”.

By focusing less on the institutional abuses of churches and more on the supposed idiocy of their followers, they provided a liberal veneer to the dehumanising rhetoric of Bush-era neo-conservatives. Indeed, they lost touch with the Christian tenet most worth preserving — “love thy neighbour”.

An unholy alliance

It’s unsurprising that the former doyens of New Atheism are now so distracted by the inflated excesses of student activism on university campuses, especially regarding the issue of transgender rights. The essence of their schtick has always been to condescendingly browbeat the “delusional” other with (in this case, dubious) “logic” and “science” — something trans people are far too accustomed to.

Their ideal university campus is one in which the freedom to be a belligerent arsehole predominates over one’s responsibility to listen, empathise and be kind.

Then as now, the political projects of Dawkins and their ilk are often, ironically, indistinguishable from those of the reactionary right. By pushing beyond contrarianism into intolerance, they wound up allied with the very forces of mysticism they set out to dismantle.

Now more than ever, we need a movement capable of critiquing the influence of religion in politics. While religion is the opium of increasingly shrinking masses according to the latest census, our political class remain disproportionately devout.

Conservative religiosity in Parliament is not going anywhere, with a recent Christian Right conference imploring evangelicals to increase their numbers in the Coalition and former Australian Christian Lobby leader Lyle Shelton likely set for a seat in NSW Parliament.

But for non-believers, it will not be the tired “old masters” of New Atheism that lead us to the promised land.

Ben, as you doubtless already understand, irreligion isn’t a single coherent body of thought. One can reject religious dogma for epistemological reasons, economic reasons, political reasons, moral reasons or even reasons of style and taste.

I personally think that emulating heroes is not the best reason to reject religious dogma: the fact that the late Christopher Hitchens was superb at calling out religious delusion and hypocrisy in both doctrine and practice doesn’t mean we have to copy (say) his drinking and smoking habits (and I’ve never entirely agreed with his politics either.)

I don’t myself object to Dawkins’ questioning (or expressing concern) about society’s sudden swing to a new paradigm of gender identity. I don’t think one can be a scientist and accept definitions by fiat: I’d suggest that traditional gender definitions and progressive gender paradigms both need scrutiny, and at the moment, for historical reasons such scrutiny needs to be concurrent: scrutinising one should not be conflated with embracing the other.

Regarding the term ‘New Atheists’, it was always a publishing/marketing category. It had very little to do with the novelty of philosophical thought (some of which dates back thousands of years): only that in the 1990s emerged a new category of monographs that could now become bestsellers, so it was convenient to turn author celebrity itself into a category.

Of the writing about gender identity recently quoted from Dawkins I haven’t seen any that could reasonably be said to have done hurt or harm. He’s simply scrutinising as is his habit; any hurt is politically construed, and the only harm I’ve seen has been in populist left-wing backlash to suppress a conversation that is and must be, acknowledged as legitimate, with real evidentiary bars that (at times) have yet to be met.

So you’re entitled to criticise and I’m glad that you are, but I think you’ve done it from the misguided premise of wanting a doctrinal leader to emulate in the first place. That really has nothing to do with the enlightenment empiricism Dawkins espouses: he’d want you to amass evidence and think it through yourself anyway.

My suggestion: stop trying to emulate other peoples’ attitudes and opinions in the first place. Instead, get better at asking questions and systematically assembling and analysing evidence.

If you’d rather produce journalism than celebrity gossip, focus on constructive arguments about the evidence, and resist the cheaper tendency to play the man.

There is no such thing as “new” atheism but merely atheism. Indeed, Huxley blunded when he introduced the word agnostic into the vocabulary.

I doubt if Dawkins will be much disturbed at losing an award to woke. Along with the rewriting of history such is the state of things to come.

Rather than display your ignorance, Bengie, come to terms with the justification for the free speech venues at UCLA initiated by the free speech movement. Gone now owing to woky perceptions of PC. As an aside, articles such as this were anticipated by Orwell eighty years ago.

The matter is about empiricism or absence of it but don’t stress yourself over it.

Erasmus wrote: Huxley blundered when he introduced the word agnostic into the vocabulary.

He didn’t blunder; he was focused on the validity of claim to knowledge by revelation. So not ‘I don’t know whether there are gods’, but ‘you cannot possibly assert that your claims to revelation have the same status as knowledge’.

But when we switch from the epistemic to religious identity, the sense changes. Agnostic is now interpreted to mean ‘I don’t know whether there are gods’., which is not the sense in which Huxley ever defined it.

And it’s a stupid reconstruction, because it suggests that your revelations can have an authority of knowledge arising simply because you claim they have it — and that I cannot know your revelations are bunkum (which is also generally not true: it’s often very easy to debunk revelation.)

Huxley’s construction of agnosticism is the right one. The subsequent (re)construction of agnosticism appears to have been watered down to the benefit of religious doctrinaires.

Under an original Huxleyan definition it’s possible to be atheistic (without gods) for reason of agnosticism (no claim of revelation has the status of knowledge.)

Rather than ‘blunder’ I ought to have emphasised the distinction is superfluous to atheism per se.

The theorological environment was quite different in Huxley’s day (with distinction of high and low Anglicanism for a start).

Agreed: revelation is synonymous with an act of faith and not of evidence which, as we know, requires an empirical means of verification (at least in principle) and an a-prior state of failure. THUS we are returned to the binary condition of athesism.

Erasmus wrote: we are returned to the binary condition of atheism

Erasmus, you’d likely be aware that the term ‘atheist’ is largely irrelevant to the irreligious. It’s the religious who need this term, to distinguish adherents of rival religions with whom they compete for influence, from those most likely to contest faith itself, whom they have traditionally sought to estrange and eliminate.

Among the irreligious, irreligion seldom matters unless and until the various privileges and abuses commonly asserted by the religious make it matter.

What matters is virtually anything else, and as you’d be aware, not every atheist is an empiricist (though disproportionately many empiricists are atheists.)

You may also be aware that ‘magical thinking’ is more of a human characteristic than a trait only of the religious. It’s pervasive enough that there’s plenty to question oneself about, and disagree with fellow irreligious about. 🙂

So speaking personally I don’t ever feel the need to use ‘atheist’ as an identifier. If someone wants to know what I am, that’s better defined in terms of what I say and do, rather than what I don’t say or do. 🙂

As for ‘new atheist’, the only thing new about criticising religion is that for the last 30 years you can write a bestseller doing it. 😉

I don’t disagree with your reply Ruv. However, given that, according to the census, about 75%+ think that there is something ‘out there’, as it were, the reply ‘atheist’ raises an eye brow, more often than not, even in an educated audience.

Erasmus wrote: given that, according to the census, about 75%+ think that there is something ‘out there’, as it were, the reply ‘atheist’ raises an eye brow, more often than not, even in an educated audience.

Yes, because of that very switch: agnostic now connotes ‘a personal belief’ when it should have remained a challenge to a conflation of conviction with knowledge.

So to say one is an atheist but not an agnostic is now interpreted as claiming superior metaphysical knowledge: an act of arrogance instead of empirical debunking.

It’s a very nasty piece of linguistic straw-manning, now over a century old and I don’t know why so many critical thinkers still tolerate it.

For your consideration here’s an alternative that doesn’t require submitting to flawed definitions in the first place…

To offer that: ‘I think there is something out-there’ invites the following critical response:

What minimum evidence would persuade you that there is nothing benign, intelligent, interested, competent and committed to your well-being beyond the few kind and respectful beings with whom you are lucky enough to already share this planet?

There generally is no minimum refuting evidence, so the statement is equivalent to: ‘I believe I’m special enough that something in the universe will ultimately look after me better than it ever reliably has.’

To which a constructive response might be: ‘We have plenty of evidence that the universe is vastly bigger than, and utterly unconcerned by, any self-important conception prescribed by humans. That same universe also predicts human conceits far more reliably than those conceits predict anything specific, significant and observable about it.’

In other words, no such conviction, however strongly held, has any claim to authority in the face of overwhelming contrary evidence that also predicts false convictions in the first place. 😀

For future reference for your armory, Ruv, the minimal evidence is the universal (2nd) law of thermodynamics. Thus the universe has a finite life to date.

The properties of quantum mechanics (observable in the lab or collider) do the remainder. Ergo, no external agent OR the hypothesis of an external agent is superfluous to the physics. As for life such is craprecious. The environment is craprecious. Yet, as with lotto, there is no place for agency.

Erasmus wrote: the minimal evidence is the universal (2nd) law of thermodynamics

Systems always creating entropy is exactly why magical thinking is so appealing to many, Erasmus.

Religious thinkers don’t use it as minimum refuting evidence but rather the reverse, and it’s often done in variations on the following line of argument:

That’s an argument from morality, and has been used by the likes of Cardinal Newman, CS Lewis and most recently, William Lane Craig. The argument itself predates our understanding of thermodynamics, but entropy fits neatly into the slot.

So if you’re willing to trot out argumentum ad ignorantium without pausing for breath, then nope, universal entropy isn’t minimum refuting evidence…

But the problem is, you can never offer minimum refuting evidence to someone willing to lower the bar indefinitely to keep their hopes of self-important revelation alive.

The same problem appears with conspiracy theorists and believers in homeopathy for exactly the same reason.

If you’re okay with indefinitely lowering the bar for evidence, then you’re really not tall enough to go on the ride in the first place, and that’s the part that needs to be pointed out.

But this is also why Huxley’s work on agnosticism is so important: no claim to revelation, whether through dreams, intuitive inspirations or fallacy-confected arguments like the appeal to morality, can be claimed as knowledge.

Dawkins, by the way, has been historically quite poor at refuting moral arguments.

He’s also pretty poor at explaining what he probably thinks as a geneticist anyway: that all gender identity is culturally-confected delusion: custom and storytelling woven around an imperfect understanding of how sex-hormones influence perception in primates. 😀 😀 😀

Certainly, Ben failed to grasp what he was actually saying and instead imagined (or believed without questioning) that he was saying the same as JK Rowling.

Let’s just keep it simple.

Anti theist is the only sane response to god botherers.

Fairy tales, fairy tales.Mose was not a real person in history and the Exodus never happened and despite what Cecil B.DeMille said, the Hebrews didn’t bulid the Pyramids.That’s only for starters, I haven’t got to the New Testament yet.

And that’s relevant to Dawkins’ erasure of trans identity how, exactly?

Wow, who knew that the Dawk had such power?

Here is a simple take on all religions: Man created God(s) in his own image.