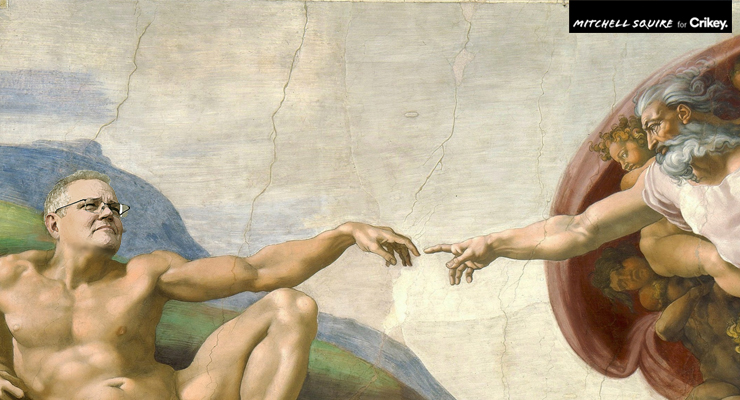

A lot of the commentary on Scott Morrison’s address to the Australian Christian Churches Conference focused on its religious dimensions. There’s been less focus on the ideological nature of the speech, which was delivered without being circulated by his office, as his other speeches are, and which was ostensibly, according to Morrison, unrelated to politics.

But while we shouldn’t pretend it provides some kind of unguarded moment of prime ministerial candour, it provides perhaps the best insight into Morrison’s core ideology, and in that sense is one of his most important speeches. It deserves to be taken seriously and engaged with.

That core ideology is deep confusion. This is one of the most incoherent speeches delivered by an Australian leader since John Kerr at the Melbourne Cup. Morrison rambles, goes off on tangents, leaves sentences unfinished. But that might just be down to its relative off-the-cuff nature — at one stage he has to stop because he can’t find the right Bible passage to quote.

But the more fundamental confusion is a tension between his conceptions of individualism and communities.

Morrison was there, he said, to ask for help from his assembled Pentecostalist brethren. “I need your help,” he said repeatedly. To do what? Many things, seemingly — “Keep doing the things that you do which allows Australians both here and” [unfinished — something unintelligible about Papua New Guinea]; “Reach out and let every Australian know that they are important created in the image of God and raise up spiritual weapons against social media.”

But most of all: “Keep building communities.”

Morrison’s concept of a community isn’t merely, or particularly, about a religious community, even though he professes a preference for “community churches”. He’s not on about that so much. His concept of community is one of a polity that meets the needs of its members in a way that he thinks has been usurped by the state and by markets. He quotes the late British fundamentalist rabbi and marriage equality opponent Jonathan Sacks extensively:

Our rights used to be how we were protected from the state. And now, it’s what we expect from it. What we once expected from family and community, now we contract this to the state and to the market.

The logical extension of this argument is that there is something unnatural, artificial, about expecting the state to provide positive rights, to provide the kind of support that families and communities used to provide. “You can’t replace the family, you can’t replace marriage, you can’t replace the things that are so personal with systems of power and systems of capital,” Morrison says. Does the prime minister believe that people who need support from the state — healthcare, education, welfare — should instead be getting those from family and community?

But that’s not what preoccupies Morrison. Instead he wants to link his concept of community with morality and individualism. Sacks was keen on linking rights to morality, though you have to read a bit more on Sacks to see how. He described rights as “noble things” but “undeliverable” without “the widespread diffusion of responsibility”. Rights are inherently linked to duties — duties are “rights translated from the passive to the active mode”. You can’t deliver on rights without being obliged to perform duties.

But Morrison then uses arch-neoliberal Friedrich Hayek to transition from the limited idea of duties to a broader idea of morality. Hayek says, according to Morrison, that freedom has never worked without deeply ingrained moral beliefs. “You lose your morality and you’re in danger of losing your freedom,” Morrison says.

That provides a notional springboard to connecting individuals, morality and communities. Morality isn’t about social or sexual issues, he says, but about “the dignity of every human being and their responsibilities. Morality is about focusing on the person next to you. That is the essence of community.”

The idea that Morrison is some glib proponent of the Pentecostalist doctrine of prosperity theology thus needs correcting. That doctrine suggests believers will be rewarded materially by God if they have enough faith and demonstrate that faith by giving to churches — a dramatic reversal of Max Weber’s linking of Protestantism with capitalism through Protestants’ desire to demonstrate their state of grace through charitable acts, investment and hard work.

Instead, Morrison offers a complex linking of individualism, personal morality, and community spiritedness via duties acting as the flip side of rights.

It’s here that confusion overtakes Morrison’s view of the world. He seems to want to short-circuit criticism of prosperity theology as a religion of greed and material wealth through the invocation of morality and community. But you can’t be a Hayekian champion of unique individuality and personal freedom and then lock individuals into Sacks’ communitarian framework where even basic rights equal duties to others.

While there have been attempts to position Hayek as some sort of crypto-communitarian, his concept of community was as an emergent property of social interactions between individuals, not a willed entity, and in an “open society” individuals had the freedom to experiment with different forms of interaction and expression. Above all, the free market — which we shouldn’t be relying on, according to Morrison — was a foundational mechanism of a civilised community for Hayek.

So which are we? Unique, free individuals or community members obligated to one another to provide support? You can be both in practice, but it’s hard to articulate an ideology that links both in theory, especially when you’re trying to base it in moral reason.

Morrison’s confusion trips him up when he turns from lauding communities to attacking “identity politics”: “There is a tendency for people to see themselves not as individuals but only defined by some group, and get lost in group, and lose your humanity and lose your connection and you’re defined by your group not by God.”

Identity politics, Morrison thinks, undermine community and self-worth.

So having lauded the idea of individuals forming communities and reaching out to others, Morrison turns on a dime to attack those who form communities. The very problem with identity politics for Morrison is that people do what he wants — “keep building communities” — but not communities he likes (Pentecostalist communities). Or, for that matter, communities like the shire, which he pauses his critique of identity politics to jokingly laud as a form of identity politics he can endorse. It’s funny because it’s true, Scott, but not in the way you mean.

Much of the criticism of Morrison’s actions as a political leader is that, ultimately, he believes in nothing; that he is merely a marketing man who can announce and present and spin, but not actually achieve. Perhaps it’s more accurate to say he does believe in some kind of ideology, but it’s so self-contradictory that it offers no guide for anything — and thus, inevitably, a justification for everything.

You may call it confused, I call it hypocrisy. I’m not sure he believes anything he says. I certainly don’t.

is a hypocrisy when everything he said or has eluded to is corruption personified, whether through his deceitful Government minions or deceit that is of his own making.

There is nothing awe inspiring about ScuMo or his minions except the corruption and dirty dealings that have been a trend!

Victoria’s missing Grants allocations, apparently caused by the Labour brethren not following the Christian principle of an falling into line over a useless tollway spiked by the outgoing brethren, seems to remain justification for a bit of Old Testament denial of fish n loaf.

Repent sayeth the Victorian voters .

Enough to put one off Pentecostalism for life. If Christianity is the game then the Penties are in the bottom half of league 2.

Eluded? Do you mean alluded?

Hallelujah brother !

What #ScottyFromMarketing has done with this speech is prove his utter vapidity and moral incoherence.

Agree but it is hardly news.

Yet sufficient numbers voted for the party of which he is the exemplar – mean, trickey & corrupt.

I would like to deal with a different aspect, one which has had very little comment.

Morrison, apparently, said that he does laying of the hands on victims of natural disasters, ie the cyclone and fires of a year ago.

Laying of the hands aims to infuse the receiver with the blessing and support of “god”.

The issue is that it is, until now, never never never done to a person who hasn’t invited or agreed to it. So Morrison thinks it is OK to force his religious beliefs on to people who do not share his opinion, who do not ask for his “blessing” (which is what he is actually doing in his belief system) and doing it to people who may oppose his beliefs or, perish the thought, may not believe in god.

So what would happen to a homeless person who walked the streets physically touching random people and justified their actions by saying I am saving them. The media would hound them, closely followed by the police and probably, as they are habitual offenders, sectioned.

What level of arrogance allows a person to do this and not for one moment think it is not acceptable.

Albanese, bless his gutless heart, doesn’t want to comment on Morrison’s actions, well he should. Imagine a CEO being an activist evangelical, well we can, because CEO’s who want action on global warming are extremists and government Ministers want us to boycott their companies.

Morrison is spiritually and physically forcing his religious views on unsuspecting and innocent Australians, and he should be told to stop.

Agree. It is creepy. I’ll bet if I laid my hands on Jenny Morrison the outcome wouldn’t be “Amen, brother”.

It got a lot of comment on ABC Melbourne yesterday. Callers thought it was creepy.

The callers were correct!

Since my childhood I have had the ability to heal, but let me tell you it drains your energy, so much so that I had to stop. Never once did I put my hands on anyone without their asking me, and I worked in hospitals but would never have done that without consent, although I have had a few ^born agains^ put their hands, unasked, on me – for some reason they seem to think they have rights no one else has. He’s lying about laying on of hands, it takes a damn sight longer than a handshake would, and his saying he did so to all those people who would have been in a dreadfully distressed state is pure, unadulterated BS. I could hardly take just being near people who were distressed, or seriously ill, I’m empathic, but I did until it all became too much for me — you have to have energy to share, and I can’t see Morrispin sharing anything let alone his energy. Come to think of it, he probably drained those people he touched.

If i could lay my hands on Morrison, I would pray that the Devil leaves him

The Devil would thank you for that, no doubt.

While the laying on of hands is disturbing, it doesn’t come close to the fact that he still believes there is an ‘evil one’. Presumably the lack of a name indicates he is talking about Voldemort.

Only the truly, deeply ignorant hold to the myth of an ‘evil one’. Most of Christianity just hides that old testament rubbish in a deeply buried closet, never to be talked about, because nobody really believes it any more. This indicates just how fringe this nutter is.

I think Scottie means Mr. Dutton when he talks of ‘the evil one.’

Funny that the bloke who savagely used Identity Politics to attack those from the “inner City”, in relation to Climate Change, is now bemoaning the “evils of Identity Politics”. Typical Right Wing Projection from #Scottyfrommarketing.

The problem here is Bernard that the alternative leader cannot get up enough momentum to destroy the image of the God botherer.

Is a dangerous precedent that this ScuMo is out there preaching and trying to push his views under guise of Christianity.

If anyone reads the Hustory of Mormons( Pentacostals) they will find a very disturbing story.

Perhaps we should stop focussing on the Leader(s) but on the messages that they and their teams send, in word and deed.

We have seen Morrisons message, we have heard his views and his Pentocostal preachings.

We have seen the deeds in his minions and there corrupt ways along with the way they treated female staffers.

This is not show and tell at some Primary School this is a Government out of control and the leader is becoming more loopy as the year draws on.

What is the alternative?

We need someone who is willing to have attack dog mentality, no holds barred a person like Keating,for all his short comings he was still better than anything on.offer now!

Shorten was pretty impressive at the National Press Club today. A comparison with Albanese was inevitable, and unfortunately Albo ain’t got what Bill’s got.

Bill Shorten has street smarts, he got rolled at last election solely on Hypocrite Hanson and Cane Toad Palmer.

Not ‘street smart’ enough to have policies to get the electorate could get excited about,

I’m staggered that Shorten is thought worth a pinch of the proverbial.

Scummo may be a hollow man but he is concrete solid compared to Shorten.

Wed morning on RN, FranK gave him the floor to talk about NDIS and this was a mistake.

He cannot speak off the cuff – only repeat whatever handlers have poured into his empty head.

After exhausting that, he did what he always does, waffle and wander.

He has no belief or principle except ‘my turn will come again’ – remember he told us after pissing away the unlosable election that he was NOT going away.

Sounds like a threat to me – “nice little party you got, appoint me leader again or something might happen to it”.

Shorten is a career politician, what the Left needs is a true believer.

Wet sloppy concrete at best. Tell me what his policies are ? Take as long as you need to think about it.

He needs no policies with this “Opposition” because they don’t/won’t/can’t.

Put another way, with enemies like AA et al, he needs no friends.

Summed it up pretty well.

Yeah, Shorten can do it when he tries. Shame the does try much – or maybe it just doesn’t get reported when he does

True but neither of them are the right gender. We need a smart, driven female leader to differentiate Labor from the LNP. Look at what happened in NZ when an astute Labour leader (Andrew Little) realised this and stood aside for Adern.

Australia is screaming out for a female leader!!

We have an ‘attack dog’ waiting in the wings, two actually. One is called Dutton and the other is called Pezzullo. Neither could be considered an improvement on our present precarious situation.

I agree too much personality and not enough policy focus I am not a fan of the pentecostal religion as far as I can see it is very superficial and materialistic..it worries me that LNP are hooked up to this thinking….Yes lets look at the team ugh and their policies ugh

How can anyone focus on something as fuzzy, bemusing and chaotic as Mr. Morrison’s messages and the thought processes that lead him to utter them?

How is it possible to focus on anything as fuzzy as Scott Morrison?

Mormons and Pentecostals (note spelling) have no connection. How would reading a book on Mormonism help understand Morrison?

A ex gf of mine was Pentacostal and they are aligned.

Do not care how you spell it, if i wanted to be as articulate as you I would have gone into elecution classes

damn i mssged myself, tarnations!!!

That’s nice. How I spell it is not the issue. What you are saying is simply misinformation. And you should stop.

Again – “Pentecostal” is how the word is spelled. And they are not aligned. They are completely different faiths. With respect to your ex, I am an academic who researches in this area, and I assure you that you are incorrect.

There is a lot of good material on Pentecostalism which will help people understand Morrison better, without reading up on a faith he does not adhere to.

But both groups are attempting to control the Liberal Party branches

Pentecostal…

Exactly right Waylaider. And VERY dangerous at a time we need less religion and more science from our leaders!

Mormons are an entirely different religion from Pentecostals. Pentecostalism is a Christian denomination accepting the Bible as their only Holy Book, accepts the Trinity, and does not believe people can become gods. Mormonism on the other hand have an entirely different concept of the Trinity, believe people become gods when they die and accept other books, besides the Bible, such as the book of Mormon.