The G7’s proposed new corporate tax minimum rate of 15% represents no major threat to either tax havens like Ireland or the Caymans, or to tech giants who are among the world’s worst tax dodgers — Alan Kohler rightly calls the deal “a bit sad”. Nor will it generate significant additional revenue for Australia. But Australian business has been quick to argue that it means Australia must reduce its company tax rate.

Straight out of the blocks was Jennifer Westacott of the Business Council (BCA), complaining “at double our 30% rate, a global minimum of 15% leaves Australia severely exposed in its ability to attract global capital.” She added that if the government wouldn’t cut company tax rates, it could at least have the decency to give business “a workplace relations system that creates jobs”, as opposed, presumably, to the current one which hasn’t generated any employment since the pandemic.

You can understand Westacott’s watertight logic — an agreement recognising that multinational firms pay too little tax and should be paying more leads inexorably to the conclusion that the Business Council’s multinational corporate members should pay less tax.

But what if many of the companies that make up Australia’s largest firms, or whom the BCA represents, really did pay a minimum of 15% company tax?

Like Chevron Australia, which in 2018-19 — the last year for which company tax figures are available — paid no tax on $900 million in profits? Or BCA member Bluescope, which paid no tax on $260 million in profits? BCA member Shell? Zero tax on $318 million in profits.

Brewing giant ABI? No tax on $320 million in profits. Woodside’s $2 billion in untaxed profits? BCA member Transurban, no tax on $158 million. Alcoa — no tax on $1.9 billion in profits. Business partner Alumina — no tax on $1.2 billion.

Andrew Forrest’s investment vehicle — no tax on $750 million in profits. $10.7 billion in profits were generated in 2018-19 on which no tax was paid at all. Ordinary taxpayers can only dream of those companies being made to pay 15%.

Or there are the corporate unfortunates who fail to make a profit at all, and thus paid no tax, despite earning billions in revenue. That would include the likes of Exxon, with $13.3 billion in revenue; oil refiner Viva with its $5.8 billion in revenue but no profit; News Corp’s $2.1 billion in profitless revenue; or Malaysian energy giant Petronas’ $1.1 billion. Such companies earned $336 billion in revenue in 2018-19 but were unable to pay any tax because they made no profits under current tax laws.

Let’s not forget the companies that earn substantial profits, but pay far less than 15% tax. Glencore paid about 10% on its $110 million in profits. CSR paid 3.5% on its $150 million profit. National Party-linked Whitehaven Coal paid 5% on nearly $300 million. Orica paid 9% on $200 million. AMP paid 10% on nearly $7.4 billion. Pharma giant Merck paid 9% tax on $69 million in profits. More than $33 billion in profits were made by companies paying less than 15% tax.

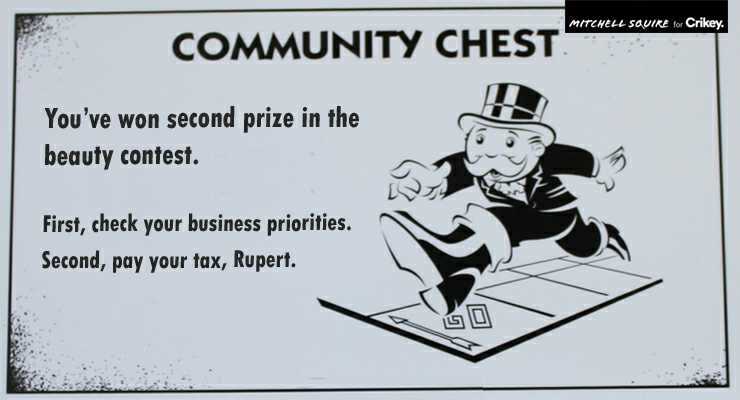

Many of these firms would have had legitimate reasons for not paying full freight, or anything at all — most particularly the carryover of previous years’ losses. But many of the biggest companies are engaging in transfer pricing, exorbitant capital or licence fee charges or dodgy accounting to channels profits offshore. Despite its railing at the tech giants about their tax avoidance practices, News Corp is one of the worst offenders in the country, and has been identified by the Australian Tax Office as a major tax threat.

A system in which global companies paid 15% in the jurisdictions in which they earned revenue wouldn’t yield huge revenue for Australia under present rules, but if the Business Council wants to use 15% as a benchmark, then it should be encouraging its members to pay at least that on their profits. And encouraging others to stop channelling revenue offshore. But that would require good faith and consistency from the business lobby.

I’m shocked, shocked I tells ya, that Morrison, Frydenberg and Robert haven’t transferred the Robodebt sleuths at Centrelink over to the ATO to chase up these companies rorting the goodwill of the honest tax-paying Quiet Australians.

But I guess they are so busy these days that this is just one more thing that they know nothing about.

Probably too busy persecuting Richard Boyle for pointing out ATO abuses & failures which were admitted and slightly corrected after he did so.

This brings tears to my eyes. Amazing what bribery and corruption can do for the bottom line. The other bottom line, that is, not the public one.

How about a $50/ton carbon tax?

all fossil fuel companies to pay $100 a tonne carbon tax. Oh don’t get me started on carbon capture…..I worked for Chevron for 8 years while they were constructing the CO2 plant that never will be……

If Jennifer Westacott really did say (or issue a statement saying) ” ….“at double our 30% rate, a global minimum of 15% leaves Australia severely exposed in its ability to attract global capital.” It’s little wonder she has to make a dollar running a business lobby. Heaven help us if she was ever in a position of having to manage the financial affairs of an actual business.

Thanks for saving my having to point that out.

Quite bizarre, unless BK has mangled the quote.

Yes, I read that a few times. Presumably ‘double’ should be ‘half’?

In other words Jennifer Westacott is a cheat!!

‘Tax? Whats that?’ ask the major corporations, billionaires & other assorted grifters at the top…..