Wage booms scare policymakers and employers alike. But what about wage slumps? Here we are, a month on from the federal budget papers: halfway into a decade-long trend of zero growth in real wages.

Worse, with the government’s policy settings, “zero” may be optimistic. The Morrison government settings are, after all, designed to hold back pay. If they keep working as well as they have been for the past five years, it will be no surprise if real wages actually fall over the next five.

The government wants to waive it off. The traditional media want to ignore it. But inside economic circles (and around kitchen tables), it’s starting to be recognised as a real threat to Australia’s future.

For nigh-on 50 years the economic boffins, from Treasury through to the Reserve Bank and on to the op-ed pages of The Australian Financial Review and The Australian, have been doggedly chasing the puttering car of wages, confident that restraint was the answer to all economic ills from inflation to deficits.

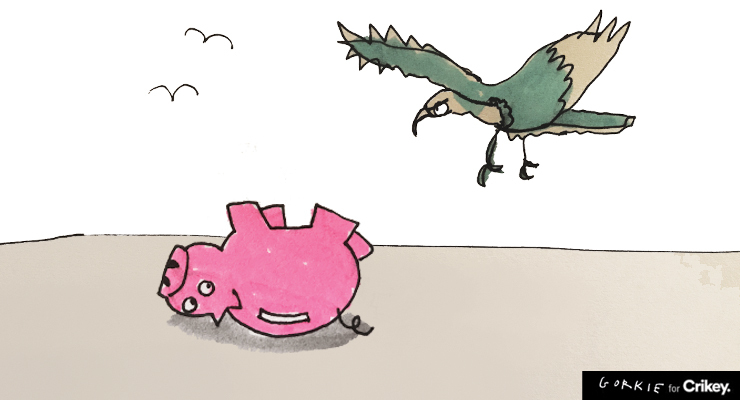

Five years after the wages car slowed and then stopped, how do those policymakers react, now they’ve caught the car they’ve been chasing? The budget papers — and the response since — suggests they’re no closer to an answer.

For the first two years after the 2016 close-call election, Treasury said last month, real wages were flat, before a fortuitously timed small blip (0.7%) in the lead-up to the 2019 election. By the next election, they predict, real wages will be down (about 0.4%) and not much different by the election after that.

Treasury has been notoriously over-optimistic in its predictions of wages growth. Fair enough. As it’s said (perhaps by Danish physicist Niels Bohr, perhaps by US baseballer Yogi Berra), it’s difficult to make forecasts, particularly about the future.

However, if Treasury’s forecasts now are only as wrong as they’ve been over the past five years, then we’re facing five years of significant falls in wages — and the buying power that goes with it.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg may be confident the economy is “roaring back” — if we ignore the wages that give the “economy” meaning). The government is relying on growth to push down unemployment, thus magicking up a wage rise through the wand of supply and demand. It’s an interesting real-life economic test: can a flat (or declining) real wage economy drive the optimistic forecasts of economic growth?

Not while all the other policies of the government are designed to hold back wages. Traditionally, governments shift the wages dial by giving unions space to bargain, by raising minimum rates and conditions (through legislation or through various tribunals), and as an employer.

Union power and individual workers (when they can) and market forces (when they must) turn the dial to positive. Employers are encouraged to push back by turning to the low-wage alternatives of casual and gig-workers (and outright wage theft).

The Morrison government? They’re busy throwing grit into the gears, making it more likely that real wages ratchet down.

Unions still influence the wages of more than half of all employees, either through enterprise bargaining (covering about one in three employees) or by shaping the minimum conditions of the awards that cover about 20% of workers. But it’s harder now to spread wage improvements that can lead to nationwide rises

While residual political fears have constrained the government from a Howard-era style WorkChoices offensive, the transaction costs for bargaining have been ramped up by criminalising activity, demonising unions and wrapping them up in bureaucratic red tape.

The government has pushed back against wages and conditions either directly (think: penalty rates) or by stacking the Fair Work Commission with ideologues to do it for them. Right now, it’s arguing against significant rises in the first post-COVID national wage case.

As an employer, the federal government froze wages for its own workers (but not its own MPs) last year and is forcing continued restraint for the 20% of the workforce employed by state, federal and local governments.

The government seems confident it can hide its wages failures behind high-vis photo ops. But as wages fall, it may have to choose between its electoral prospects and its low-wage DNA.

Is the lack of wages growth something that worries you? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. (Please include your full name to be considered for publication in Crikey‘s Your Say section.)

“The government seems confident it can hide its wages failures behind high-vis photo ops. But as wages fall, it may have to choose between its electoral prospects and its low-wage DNA.”

What failure? The government wants wages to go down and they are going down. That’s success. The government works for business, not for the little people, and business does not hide its desires. Who could forget Mrs Rinehart’s speech from 2012?

“The evidence is inarguable that Australia is becoming too expensive and too uncompetitive to do export-oriented business… Africans want to work, and its workers are willing to work for less than $2 per day. Such statistics make me worry for this country’s future.”

We still have some way to go before we can compete with those marvellous Africans, but the government is not going to let up. As for its electoral prospects, there are plenty of ways the Coalition can stay in power without the shame and embarrassment of running good policies. We should at least have learned that by now.

Public and private company executives are receiving huge wage increases via obscene bonuses, the wealth needs to be shared amongst us all. It’s our productivity increases and unpaid overtime that achieve their performance goals, usually without any thanks never mind a financial reward!

That would be only a few hundred people and it’s macro effect is minor.

The lack of wages growth isn’t something that worries me. The lack of livability on the wages people get is a bigger worry. Wages growth has that “here we must run as fast as we can just to stay in place” problem with it. There’s plenty the government can do to take away the ever-present financial pressures most Australians endure to a degree. Instead the costs of living rise with our paychecks.

An LNP government taking action which would be displeasing to its sponsors will not happen, therefore continued wage depression must have been given the tick of approval by the BCA other right wing propaganda bodies.

Unfortunately wage earners or working age population can be thrown under the bus due to changing demographics i.e. ageing population and more voters no longer in the working age cohort but retired.

Outside of safe or unchanging electorates, many (especially regions) are becoming more dominated now by retirees and baby boomers in or transition to retirement….. a powerful electoral cohort with guaranteed minimum income and benefits support.