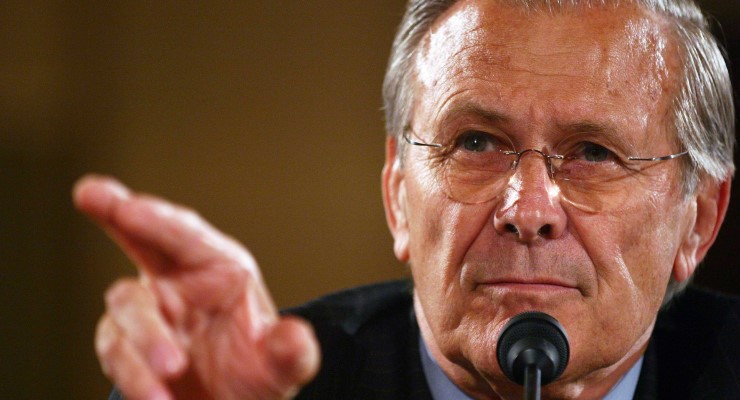

Donald Rumsfeld, the former US defence secretary who died this week at the age of 88, was a latter-day exemplar of what the journalist David Halberstam called “the best and the brightest”: a shining intellect and commanding personality who in the end was brought down by his own overconfidence.

Rumsfeld, an ultra-hawk who once declared “I don’t do quagmires” is likely to be most remembered for his pivotal role in orchestrating the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the two-decade-long quagmire in Afghanistan.

A standout collegiate wrestler at Princeton University and former naval aviator, Rumsfeld rose swiftly in Washington, holding the same job at two very different times in American history. In 1975, at 43, he became the youngest defence secretary ever under president Gerald R Ford, and then in 2001 he took on the job again as one of the oldest Pentagon chiefs ever sworn in. Much earlier in his career, starting in the 1960s, he served as a three-term congressman from Illinois and then as head of president Richard Nixon’s Office of Economic Opportunity, helping to orchestrate the rise of his long-time friend Dick Cheney in politics. In between, he became a Fortune 500 CEO and turnaround specialist.

Through it all, Rumsfeld was a dyed-in-the-wool conservative. During the Cold War, he sought to defy Henry Kissinger’s policy of detente with the Soviets and pushed for a major military build-up, pressing for the development of cruise missiles and the B-1 bomber. And after he became president George W Bush’s Pentagon chief, Rumsfeld was, along with then-vice president Cheney, one of the key members of the administration who pressed Bush to move quickly to target Iraq, not just Afghanistan, after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Square-jawed and squinty-eyed, Rumsfeld relished playing the tough guy and the embodiment of American power — Bush once described him as a “matinee idol”. It was ironic, therefore, that he ended up exposing the worst vulnerabilities of American power through a series of decisions that led to his firing in 2006. Rumsfeld hoped to achieve major results with only a “small footprint” of a few troops. He succeeded at this in Afghanistan in the early days, ousting the Taliban in under two months in late 2001 using laser-targeted joint direct attack munitions and other bombs dropped from B-52s.

But then things began to go seriously awry in what was at the time called the global war on terrorism. When Gary Berntsen, the CIA officer in charge of the operation at Tora Bora, believed he had Osama bin Laden trapped in December 2001, only three months after 9/11, he pleaded with Rumsfeld and other superiors in Washington to send troops. Rumsfeld turned him down, arguing that Pakistani forces would trap bin Laden as the Afghans forced him southward. (Instead, the Pakistanis were likely to be helping bin Laden to escape.)

And when James Roche, then the air force secretary, asked him to reconsider his support of the Iraq invasion in the fall of 2002 — saying, “Don, you do realise that Iraq could be another Vietnam?” — Rumsfeld all but threw him out of his office, according to Roche. Rumsfeld, whose main desire was to exorcise the ghost of Vietnam forever — restoring American power and prestige in the world — was outraged at the very suggestion. “Of course it won’t be Vietnam,” Rumsfeld said. “We are going to go in, overthrow Saddam, get out. That’s it.”

But none of it worked the way he wanted it to. Not only did Rumsfeld fail to follow up on the pursuit of bin Laden and his lieutenants at Tora Bora, but he decided to minimise stability operations and confine peacekeeping to Kabul. “When foreigners come in with international solutions to local problems, it can create a dependency,” Rumsfeld explained in a February 2003 speech. That restraint, however, only opened the way for the return of the Taliban. At about the same time, Rumsfeld turned his attention to making war on Iraq, albeit without an occupation plan. (Again, he wanted to leave quickly.)

Then, after orchestrating the invasion of Iraq, he remained in denial about the growing insurgency there, infamously sputtering at one news conference: “Stuff happens.” His lack of oversight helped produce the atrocities at Abu Ghraib and other prisons. Finally, as Rumsfeld’s inattention to Afghanistan and the violent insurgency in Iraq began to cost more and more US lives, Bush fired him in 2006.

Rumsfeld was not blind about Iraq. He foresaw the pitfalls of a long foreign occupation, calling it “unnatural”, like a bad set of a broken bone. He planned to reduce the US presence in Iraq to some 30,000 troops within months of the March 2003 invasion. But when things did not go his way, Rumsfeld’s habitual tendency was to simply insist that his critics were wrong. Rumsfeld, for example, defied repeated advice from senator John McCain and others that the US troop size was too small to quell an insurgency.

By the time he went into retirement, many military experts were comparing Rumsfeld unfavourably to Robert McNamara, “the best and the brightest”-era defence chief who orchestrated the Vietnam War. “Whatever McNamara’s sins in getting deeper into the ‘deep muddy’ [Vietnam], he was at least trying to do something about it. Rumsfeld demanded responsibility for all of postwar Iraq and then did nothing with it. He tried to destroy the interagency process. And I think he was successful,” one senior Pentagon official told me at the time.

In the end, as the journalist George Packer wrote in his book The Assassins’ Gate, it may have been Rumsfeld’s sheer longevity as an official that led both him and Cheney into the folly of Iraq. “Through the three decades of their public lives, the only thing America had to fear was its own return to weakness,” Packer wrote. “But after the Cold War ended, they sat out the debates of the 1990s about [transnational terrorism] … When September 11 forced the imagination to grapple with something radically new, the president’s foreign policy advisers reached for what they had always known. The threat, as they saw it, lay in well-armed enemy states.”

There is natural sympathy for Rumfeld’s relatives and friend, but none at all from me on hearing of his passing. He, Cheney and Bush did immense and devastating harm to global civilisation. Rather than fighting ‘the war on terrorism’, they needlessly created an enduring version of it. This changed (substantially for the worse) the lives we lead today. On behalf of all those who suffered and died because of his hubris and hegemonic inclinations: A pox on his house. Good riddance.

Hope he hasn’t packed anything warm.

Ouch!

Another war criminal of the Blair, Howard, GW Bush era and finally did something of benefit to the world by going home to old Nick, big party in hell tonight with a lot of war stories to tell. god just flushed the world`s toilet.

And the “embedded” Murdoch, the epoxy that stuck them all together.

Will there be a rubbish tip somewhere to accept his carcass.

One of Greg Sheridan’s heroes.p

Greg Sheridan, just a shill, paid by NewsCorpse, for the LNP… who believes in “All the Way with the USA” … was a rabid attack dog in the kennel at The Australian, just hoeing the Neocon Cabal line out of The White House before, during and after that illegal, immoral stupidity that was the The Iraq Fiasco, as well as that earlier stupidity, The Afghan Imbroglio