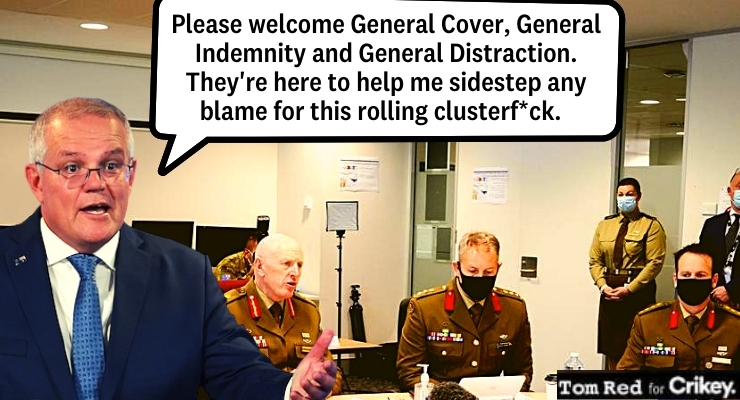

The fact that in the last two weeks we’ve seen more of “COVID-19 Taskforce commander” Lieutenant General John Frewen than the prime minister, while the country’s largest city was back in lockdown along with much of the rest of the country, isn’t an accident.

Since June 21, Morrison has done five interviews and two media conferences, the most recent last Friday after the national cabinet meeting. He hasn’t been seen for nearly a full week.

In the same time period, Frewen has done four media conferences — one with Morrison — and six interviews, including two this week. He’s often been accompanied at media conferences by another military figure, Commodore Eric Young.

It’s reminiscent of Operation Sovereign Borders, when Morrison used a military uniform, filled by Angus Campbell, to impart authority to the operation and justify a persistent refusal to share any information about “on-water matters”.

Back then, though, Morrison would present at media conferences to refuse to provide information. Now he simply doesn’t hold media conferences.

To do so this week, to even call his usual 2GB radio interlocutors, would be to invite difficult questions about the Sydney lockdown, given Morrison’s previous endorsement of Gladys Berejiklian’s “gold standard” management of the pandemic and his support for her previous refusal to enter lockdown. And difficult questions about the culpability of the Commonwealth around quarantine facilities, the general vaccine rollout and, most particularly, the failure to vaccinate aged care workers, which was a specific Commonwealth responsibility that cannot, even with the most Morrisonian casuistry, be sloughed off to the states.

Other questions might also crop up — about his treatment of Julia Banks, about the presence of an alleged sexual harasser in his cabinet, about the Nationals’ failure to properly resolve allegations of sexual harassment against Barnaby Joyce, about his role in the car park rorts scandal.

It was somewhat different with Victoria’s most recent lockdown, when Morrison referred to that state as choosing to go into lockdown, and declining to offer any financial assistance until the optics looked so bad he was compelled to. Now Josh Frydenberg has been left to deal with Dominic Perrottet’s calls for help.

There’s something to be said for a “less is more” approach to prime ministerial media, rather than feeling the need to fill the news cycle, respond to every trivial issue and incessantly feed the media’s demand for announcements. But that’s during business-as-usual, and this is anything but. The vaccination program is off the rails, Sydney is locked down, a new virus variant is wreaking havoc with planning, and there’s growing evidence that people in Sydney aren’t paying much attention to lockdown rules. A national leader has to lead in such circumstances.

But Morrison’s last two media conferences have proved damaging. Last Friday’s media conference to unveil the halving of passenger caps, forced on him by the states, and a meaningless “four-point plan” out of lockdown. The one before that, from quarantine in the Lodge, was the now-notorious press conference where he appeared to urge young people to get AstraZeneca, leading to a week of bitter Commonwealth-state fighting. Is he worried his once sure touch in managing the press gallery is starting to slip?

Morrison had already ceded enormous power to state premiers. Now his absence makes him seem even less relevant, as if he were more ceremonial president of the federation than an actual political leader, waiting for a state funeral or royal visit to emerge and undertake his duties — or, at least, for the media to move on from Julia Banks, and Barnaby Joyce, and sexual harassment, and other inconveniences. When will it be judged safe for Morrison to come out of hiding?

The man has serious character flaws which are highlighted by his belief in miracles and burning bushes and virgin births and ‘good’ will triumph! Incidentally, why was he rissoled from the Australian and NZ tourism jobs?

For gross financial mismanagement – ie – doing to them what he is now doing to us.

And from the bits and pieces that can gleaned from his tenure in those places: he was also a divisive and often absent manager, who had a tendency to blame others for his failures, while taking personal credit for achievements that he had little or nothing to do with.

Sounds familiar.

And, one hears around Canberra, he is also bad-tempered. The Laura Tingle interview with Julia Banks seemed to provide confirmation of these traits.

Spot on, that’s the guts of why he’s been sacked repeatedly. Have posted some of it above, suggest a google of Michael West

Its best to pray alone.

Information on those matters is a closely held secret to never be released. I think he’s afraid that if we knew the truth he would never be re-elected.

Like the secret AZ contract a matter of national security no less. Scumbo’s been claiming this for eternity, praise and clap altogether now, Michael West has all the guff on the sneaky little toad:

the Senate committee looking into government advertising also requested Tourism Australia table the KPMG report.

Tourism Australia on 25 November 2005 responded: “Tourism Australia requested internal auditors, KPMG, to undertake a review of the tender evaluation process to assist the Board with their review of the recommendation to be received from management. The report is considered to be commercial in confidence.”

national security = political embarassment

Yeah the same reason Morri$in got the sack in NZ and here before Howard chose him to be his future rodent self.

Let’s incentivize Fran Bailey to spill the beans! She sacked him maybe that is why he hates women.

Been wondering why Fran has remained silent. Have any journos asked her?

As Guy Rundle writes:

” It is not Scotty from marketing but Scotty the son of a Christian evangelist cop-mayor, a man who ran a local council like a fiefdom for years. Of course he turns to the military as his total mismanagement of the situation becomes impossible to ignore.”

https://uat.crikey.com.au/2021/07/07/administration-with-authority-how-putting-the-vaccine-rollout-in-military-hands-is-corrosive-for-the-country/

Pollies setting up Military Leaders to be blamed when all goes wrong? What is new about that?

This cunning plan dates back centuries. scotty (from marketing), is only following what the Brits. and others have done, since Hippocrates ran a corner Chemist shop.

The happy look on general Whatsisface says it all he knows it’s a set up. If all goes well, the pollies will claim they fixed it all. If all goes badly the general is up the creek, and scumo comes out smelling of roses.

The military are an insurance policy in times of peace.

We are on a war footing according to one of Morrison’s earlier meanderings.

So Kip Denton’s title ‘Scapegoats of the Empire’ come to mind with the wretched behaviour of the leader of the LP during the pandemic.

https://kangaroocourtofaustralia.com/2020/10/10/scott-morrison-was-sacked-as-managing-director-of-tourism-australia-for-financial-fraud-why-should-we-trust-him-with-our-money-now/

Scott Morrison was sacked as managing director of Tourism Australia in 2006 with a year left to run on his contract. For 14 years the reason for the sacking has remained one of the best kept secrets in Parliament. Now, FoI documents accessed by Jommy Tee reveal the PM either lied about a critical probity report, or numerous government departments and agencies are so incompetent that all of them – together, coincidentally, jointly and severally – lost it.

He was sacked for doing exactly what he’s been doing since elected, in every capacity he’s been stashed

it is clear that the lack of transparency and accountability surrounding the $180 million tourism campaign – the oft-ridiculed “So where the bloody hell are you?” – and the awarding of a contract to M&C Saatchi played a key part.

The campaign’s tender process was criticised by the advertising industry, with players bemoaning that the tender criteria were skewed towards a particular agency.

Following repeated calls by the opposition for more probity, word leaked to the media that KPMG had been called in to conduct a “probity audit”. The Age declared that KPMG had been hauled in to “give an impression that the selection criteria is kosher”.

No media release announcing KPMG’s appointment as probity auditor exists in the archived websites of Tourism Australia, the department of industry, and that of the minister, Fran Bailey.

However, the plot has thickened considerably with FoI documents obtained this week by Michael West Media revealing that the probity report supposedly conducted by KPMG, a report that Scott Morrison repeatedly used to shield himself from attacks over the awarding of the $180 million contracts, cannot be found anywhere.

Moreover, Tourism Australia was unable to find any emails, briefings or tender documentation associated with a probity audit into the M&C Saatchi contract.

For anyone to believe things would be different if he became an MP or god forbid the PM, shows a leap of faith astounding in its agility.

A while back, psychologists Hare and Babiak published the book, Snakes In Suits. It was essentially a guide for HR departments, on how to spot high functioning psychopaths, before they do too much damage to their particular workplace. To anyone who’s read the book, Morrison’s work history would set off alarm bell after alarm bell.

There is no doubt in my mind that Morrison qualifies for a DSM classification as psychopath. I was just reading about Herbert Armstrong another contagious bully coward and dangerous person

I just read that, Where the bloody hell is it; which you mentioned later in the thread. If correct, his claim that his performance was investigated and supported, by an auditor’s report that doesn’t seem to exist and that he may have made up, is pretty well textbook.

Not at LNP HQ though, they actively seek out psychopaths and sociopaths for high office, it is in their DNA.

I have to say that I think that that really is the case when you look at the array of Misfits cranks skonks and psychos on the benches

I’ve been wondering lately, if democratic tendencies in societies, are actually long running attempts to limit the power of psychopaths and narcissists. I mean, traditional monarchies, where the royal youngsters were taught that their privilege was the will of God, would appear to have been the perfect breeding ground for rampant narcissism.

Joe ‘leaner’Hockey said he was like PAC-MAN of the old Atari game. Relentless,24/7,politics,chomp chomp chomp,must destroy enemies,secret men’s business,etc.He also needs to shove his religious beliefs up the arses of the infidels of Australia.

Lack of proper governance procedures especially financial management and staff management. Interesting that Helen Coonan( former Coalition Senator as the Chairperson shunted him off.

Apologies folks, it was not Helen Coonan that precipitated his departure, it was Fran Bailey. I must have had a Crown moment

I believe in burning bushes too… at least since December 2019.

Fraud and theft.

You read him like a book Bernard and what a horrific read it is.

Yes, and a long list of chapters.

‘How we optimised aged care transmission by casualising the workforce; how I hectored Victoria to re-open schools in May 2020 because kids don’t transmit and then got a 170-case secondary college cluster in July; how I built the Covid app; how I thought that buying ‘home brand’ and not having too many messy vials left over was our best purchasing strategy; how I refused to start developing MRNA technology until mid 2021; how I refused to build Commonwealth quarantine and left the premiers holding the bag (ha!); how I refused to implement a vaccination indemnity system like other OECD countries; how I decided vaccinations for aged care staff and disabled people weren’t important; how I asked the EU and the US to help us out with vaccine supply after I’d told them to f**k off with their emissions reductions.’

Gotta be a bestseller.

Volume two: What Scotty did next. Nothing

It’s alright, he’s too busy starting a “gas led recovery”.

We are all in the chamber with him.

Hiss….

Gas lit recovery…

Yes and the book is Where’s the Wally?

It is called Operation COVID shield because it is intended to shield Morrison, not the rest of us.

Good one!!! So true in fact.

The appointment of a goddamn lieutenant general to a role in civilian government, in consultation with business heads and excluding unions, community groups and, you know, parliament, should be on the front page of The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, and Guardian Australia. Instead there is anything but….Guy Rundle

Is he worried his once sure touch in managing the press gallery is starting to slip?

Is that he same press gallery that his office backgrounded about the breakdown (??) of Julia Banks and the employment problems of Brittany Higgins’s partner?

It is bad enough that the PM does only announceables and backgrounds against women who expose his government’s sleazy behaviour. But that a gullible press gallery accept those announcements so unquestioningly is even worse.

National press Gallery wiki

Studios for the major TV networks are among the gallery; including the ABC, SBS, Channel Nine, Channel Seven, Channel TEN and other media partners.

Major newspapers that participate in the gallery include The Australian Financial Review, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, The Australian, The Daily Telegraph, the Herald Sun, The Courier-Mail, The Advertiser, The Canberra Times and Inside Canberra, as well as playing host to Fairfax radio’s 2UE/3AW and to Sydney station 2GB.

How may independent media sources are part of the press gallery?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canberra_Press_Gallery#Media_affiliations

2 out of 15 when I looked last, those being the compromised ABC and SBS

This is the standard MO. Lie low for a while and then create a distraction,

The problem is that the last two distractions left him bleeding from both feet.

He is lying low trying to figure out when it will be safe to do so.

Government is now a Game of Clowns – and winter is coming.

There is a strong resemblance between the white walkers and the soulless ministers of this government. Il Dutte has the blue eyes too, doesn’t he?

Barely humanoid

Are they his?

He has no idea in pure and simple terms. A dangerous ideological zealot masquerading as a ring master in a circus of clowns thsat is L/NP.

Reverse of beam me up Scotty is beam Scotty up as he is not a intelligent life form!

Bring in the medals and uniforms, that’s his answer, make it a secret military led operation; can’t point the finger at dirty little scummo then.

”I do not believe that Lieutenant General John Frewen is personally, in any way, anti-democratic. But his appointment represents a corrosion of the democratic commitment. ” Rundle

And when he does return, he will undoubtedly claim to have previously answered, all the unanswered questions.