Just as the government was recently releasing its Intergenerational Report spelling out, yet again, the need for higher productivity, more migration and higher participation to protect us from the consequences of an ageing population, it was busily undermining its message.

On July 1, changes to the allocations and priorities of the government’s skilled migration program commenced, in which — according to then population minister Alan Tudge last year when he announced them — “priority within the skill stream will be given to Global Talent [visas], the Business Innovation and Investment Program (BIIP), and Employer-Sponsored visas”. That included the doubling of the number of BIIP visas to 13,500 in the 2020 budget and the tripling of Global Talent visas to 15,000.

The BIIP category means that 13,500 people a year will in effect be able to purchase a visa for long-term residency in Australia — and a pathway to permanent residency — if they can bring enough assets with them, on the basis that they will be bringing additional innovation, business skills and investment into the country.

As a report by Grattan Institute in May demonstrated, however, the scheme is a colossal failure. For a start, it’s a solution in search of a problem — Australia does not lack for capital, being now a net exporter of capital due to our massive superannuation system. A visa scheme to encourage investors to move to Australia thus looks like a 1980s solution to the days of “horror foreign debt” headlines. And the “investment” brought by visa holders mainly goes into retail and hospitality businesses, rather than areas where Australia business has traditionally been weak or lacked innovation.

The results of the scheme, the Grattan authors demonstrate, are abysmal, both within the terms of the scheme itself and for the priorities we are supposedly pursuing in the context of an ageing population.

Investor visa holders are much older than other skilled visa holders, with the great majority between 35-54 compared to 15-34 for skilled visa holders. More than a quarter of investor visa holders are considerably older than 37-38, the average age of Australians.

And contrary to the rationale for the scheme, visa holders earn much less than other skilled visa holders — a median income of $25,000 compared to one of $64,000 in 2016 — and work less, with half of visa holders not participating in the workforce. They are less well-educated, with just 10% holding a postgraduate degree compared to a third of skilled visa holders, and 60% having no degree at all. Investor visa holders also bring in more than twice as many secondary applicants — family members — as other skill categories.

And remember there’s an opportunity cost to each of these visas that brings in a less educated, lower-earning, older migrant — we lose a younger migrant more likely to be skilled and to be participate in the workforce. That’s why the Grattan report recommends dumping the visa category entirely.

Unlike the investor visas, there are no points requirements around assets to meet for the Global Talent category — as the Grattan team of Brendan Coates, Henry Sherrell and Will Mackey points out, the category has virtually no criteria beyond vague adjectives like being “exceptional” or “international recognition”, to be judged by bureaucrats, and that they will readily find employment, preferably at a salary above $153,000 (although that isn’t a requirement) and are from ten target sectors. Home Affairs also uses an expression of interest process to filter applications or nominations — companies can nominate people for visas, even without committing to employ them.

The Global Talent category began as a trial in 2019 and is so new there’s little data on which to base any assessment, but that hasn’t stopped the government massively increasing it. The program is reminiscent of the migration program of the pre-Robert Ray era, when ministers and the department had almost unlimited discretion about who was allowed to enter Australia. And beyond the high level of discretion, Home Affairs devotes considerable resources to assisting applicants in their application process, adding to the cost burden.

As always, best to ignore what the government says about its policy priorities, and look at what it does.

There is much more to say on this topic. The Grattan Institute’s recent report has highlighted the flaws in permanent immigration policy that Bernard Keane is reiterating in this article. However, whilst not a major part of their report, the Grattan Institute is also indicating major problems with the temporary immigration policy, which is the “backdoor” for many low skilled workers that have, in recent times, flooded into our hospitality and aged care employment sectors. The Grattan Institute is, I understand, preparing a separate report on temporary immigration.

Both the Grattan Institute and the Australian Population Research Institute consider this large influx of low skilled immigrant workers is suppressing wages. There is growing support for this position. No less luminaries than Dr Phillip Lowe and Bernie Fraser (current and past Reserve Board Governors) are reported as having a similar opinion about immigration suppressing wages growth. For some time Labor’s shadow immigration spokes person Senator Keneally has been expressing a similar view particularly with respect to the temporary migration backdoor.

In their paper, the Grattan Institute suggest that raising skill requirements for immigrants will have the reverse effect – it will raise local salary levels.

The current immigration policy needs much more debate and a major reset before the pandemic subsides and we open up again. If I was to paraphrase the arguments being put by all these individuals and institutes it would be that we restart immigration with quality rather than quantity.

Excellent summation of the reality of the immigration bonanza set off by Rodent Howard

Great suggestion.

Pity it won’t happen.

Immigration policy appears to be a jointly authored by the usual suspects-property developers, big business and higher education.

Good luck getting their noses out of the trough.

In the end it’s merely another argument for a federal ICAC.

And shockingly we have to watch; some think tank “expert” on The Drum exclaim Australia needs to import people with skills and qualifications”; of course because “we” the Aboriginal and existing citizens are not deigned worthy enough; such a lot of propaganda….driven by neoliberal ratbags

Two things, beware the radical right libertarian trap’ (getting everyone talking about ‘immigration’ negatively, now deceased John Tanton) and what credibility does the Australian Population Research Institute (APRI) have in demography, yet they are referred to often by some media?

Another, there is no peer reviewed evidence anywhere showing that (undefined) ‘immigration’ suppresses wages and/or creates unemployment; government policies however do impact the economy…. but easier to play ‘divide and rule’ pitching ‘immigrant’ workers against ‘Australian’ workers.

Further, Grattan Institute and others have been using the inflated estimated resident or raw population data derived from the ‘nebulous’ NOM net overseas migration (unique to only Oz, UK and NZ then inflated by the UNPD since 2006?) to base (flawed) research e.g. claiming a chunky population pyramid i.e. sufficient working age population (15-64 drawn from same), to support increasing numbers of retirees into the future. This then supports nobbling superannuation and claiming increases in SCG (super contribution guarantee) are not needed as pensions would be sufficient (and NOM if relevant, will apparently remain significant though dependent upon students from India/China), too cute.

False, like elsewhere we are headed towards not a population ‘pyramid’ but ‘arrow’ with a heavy head representing dependents i.e. mostly retirees vs. lower fertility rates for children but supported by only a slim shaft of tax paying working age ‘permanent’ population.

The demographic population analysis in Australian media defies statistics 101 and to be valid, the actual working age population needs to be filtered and supported by detailed research (including qualitative), not headline numbers then making subjective judgements.

First, requires analysis using actual permanent working age population ex. NOM, then using population including the NOM of visa holder types with full work rights (includes many new permanents from offshore), then 2nd year backpackers, then the tricky bit on actual behaviour of international students on temporary visas with restricted work right needs to be researched first hand, to parse through very mixed up data. Only then can one offer grounded and meaningful dependency ratios, that are avoided by many of the same and media as they may tell a future story…..

As it is many supposed experts, including APRI, SPA etc., use the NOM and/or student visas now as a proxy for ‘immigration’ and/or ‘work visas’ without any analysis of significance, then media assume all students work; both depersonalising and stereotyping negatively hence a dog whistle.

The ‘population growth’ and ‘immigration’ dog whistles have been running now for two decades (and further with fossil fuel supported ZPG) by the usual suspects and promoted by unquestioning media then put into action by far right mosque shooters, Trump White House, insurrectionists at Capitol Hill etc.; embarrassing in Oz when other nations are waking up to it…..

You must in some way benefit from the immigration ponzi scheme unleashed upon this nation by John Howard and his Coalition with the aim to suppress wages and reduce our working conditions all of which have been achieved.

Nothing mixed up about the data the fair work ombudsman has concerning wage theft but that is not what you want to hear you prefer an echo chamber

Wow. This is fascinating. Is there any possibility that the government has found a correlation between the sort of rich idle ill-educated dimwits that apply for these visas and – if they eventually become citizens – voting Liberal? Which would distinguish them from the sort of young hard-working post-graduate migrants we might otherwise attract? Is the government capable of thinking that far ahead?

If that’s not it, what on earth is the government trying to do?

Yes it’s hard to understand the motivation, most likely we are only being told the convenient half of the story.

Otherwise it just makes no sense at all.

“Idle” and “dimwit” make no sense unless the “rich” in some way negates it to the betterment of the country.

Exactly, think it’s why the IPA supports (undefined) ‘immigration’ for employment and/or wealthy investors, provided the former do not have access to permanency, then citizenship and voting rights….

Is it an Education Industry or an Immigration Industry?https://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2021/07/is-it-an-education-industry-or-an-immigration-industry/

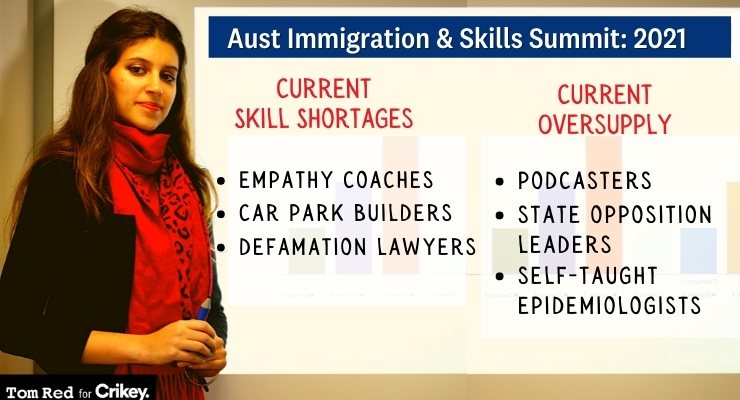

By the way, full points to Crikey and Tom Red for the check list on current skill shortages and oversupply. I couldn’t stop laughing. You have missed one important skill shortage though – gold standard managers of pandemics.

One of the shortages a while back was for Chinese speaking real estate agents I kid you not

Don’t fret, there is a long standing permanent residency visa scam that ensures young Chinese and Indians who make up the bulk of the foreign students get permanent residency after buying their degrees and working for 2 years for next to mothing.

Not true and a broad negative stereotype accepted too easily in Oz; all successful permanent migration applications, whether onshore or offshore, come under the annual cap (160K) along with refugees, family reunions etc..

You should not be so devious with your figures.

In the year ending 30 June 2020 there:

https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/migration-australia/latest-release#net-overseas-migration

NOM is not permanent migration, it’s ‘churn over’ of border movements (of those staying 12/16+ months) but presented as ‘immigration’ suggesting permanent, which it is not.

In any given year NOM is not permanent migration but over the long term the trend or average NOM is. This is just maths.

Before 2004/5, NOM was fluctuating around 100,000 per year and after 2004/5 it suddenly jumped to around 200,000 and has stayed fluctuating around this level ever since. This is a doubling of our immigration intake over the last decade plus.

The Government has reduced the permanent immigration ceiling from 190,000 to 160,000. However what that means is that those on temporary visas will have to wait longer for their status to be clarified or made permanent. This is not satisfactory for the immigrant or the Country. That is, unless your interest is primarily a steady supply of cheap labour.

Correct, it is telling that Drew is more interested in misleading readers about the level of immigration to the nation, we have higher population growth than some third world nations, totally unsustainable and undesirable, unless you profit from a never ending supply of consumers.

Good old ‘cite and paste’ MacroBusiness with daily headlines for an ageing white male audience about the problems of modern day ‘immigrants’ and ‘population growth’, channeling Bob Birrell’s APRI data analysis and negative conclusions on ‘immigration’ via Birrell’s own protege at MB, Leith van Onselen; radical right libertarianism masquerading as right on centre.

I can imagine how frustrated you must be with citing references I noticed that you don’t, and I can understand why you are unable to do so, given the content of your posts.

Everybody intending to stay in Oz for 12/16+ months is picked up by the NOM including citizens and PRs but generally the latter cohorts are removed before analysis.

However, what is left are no less than six visa categories with potentially 65 different visa sub-categories….. that precludes headline analysis of the simplistic NOM headline number i.e. no conclusions can be drawn, but they are….

Further, US media are awake to the modern ‘population growth’ and/or ‘immigration restriction’ types (since fossil fuel supported ZPG), especially after they advised Trump along with mainstreaming their messages via media, and now apparent in the UK.

Dr. Joe Mulhall, senior researcher at European anti-extremism NGO HOPE not hate, along with other researchers looking into the international far right, found they were missing part of the puzzle by taking public manifestations at face value, till recently i.e. discovering the involvement of the far right in the weaponising of climate, immigration and population.

In fact they were only partially correct as the same can be linked back to the eugenics movement etc., and is joined at the hip with radical right libertarians who also supported Trump’s administration.

https://www.macrobusiness.com.au/?s=immigration

We have one of the largest per capita immigration programs in the developed world with just the skilled visa rorts alone pre covid bringing in around 4,000 new arrivals a week.

There’s a restaurant in a well-heeled part of Melbourne that re-imagines itself every two years. The area is short of restaurants and this building could certainly survive as a restaurant under good management. But every two years the signs a replaced – no changes to the restaurant itself – now Japanese, now Vietnamese, Chinese… Presumably every two years a new immigrant “invests” in the business.

Either that or it’s a money laundering enterprise…or maybe both