Australia’s outgoing human rights commissioner has sounded the alarm about Australia “sliding into mass surveillance” if it continues to embrace the use of facial recognition technology. Edward Santow also criticised governments using the spectre of terrorism to pass broad laws that infringe on Australians’ privacy and end up being used for other purposes.

These remarks come after the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) published a long-awaited report on human rights and technology in Australia. It took the significant step of recommending a temporary ban on the use of biometric technologies like facial recognition in areas of decision-making that are considered high-risk, such as by law enforcement or for government services.

Santow, speaking at a webinar hosted by Monash University earlier this week, reiterated his concern about how facial recognition technology in particular presents a real threat to Australians, both due to the limited accuracy of technology and the risk of mass surveillance.

These concerns primarily focus on one subsection of facial recognition technology. “One-to-one” facial recognition, like the face-scanning used to unlock an iPhone, tends to be accurate and less controversial.

What’s more troubling to Santow is the use of “one-to-many” facial recognition, which is when multiple people are scanned by the technology looking for matches — such as when scanning a crowd for matches to a list of faces. He said this use of the technology tends to be inaccurate, particularly when it comes to women, people of colour and people with disabilities.

This can lead to cases where wrongly identified people are negatively affected, such as in the case of an African-American man in Michigan who was wrongly arrested because facial recognition thought he was someone else.

Santow also said some researchers and companies are proposing to use the technology in ways that aren’t supported by a wealth of evidence: “We can slide into phrenology really quickly when we use facial recognition to purportedly record someone’s emotional status.”

But even if the technology was 100% accurate, Santow fears that use of facial recognition — by governments, police or businesses — risks removing Australians’ right to privacy. He said widespread adoption could curtail people’s ability to move in public without being watched.

“It’s a bigger philosophical question whether we want to be a country that leans into facial recognition at a public scale. There’s a bigger issue at stake: we’ll become a country that accepts a much higher level of surveillance than we ever have to date,” he said.

Santow also condemned governments introducing broad surveillance measures and laws under the guise of national security matters, despite having much broader proposed uses.

Using the example of the Identity-matching Services Bill 2019, which proposed to use state driver’s licence photographs to create a national database for facial recognition technology, Santow said the federal government’s arguments for the bill reductively focused on combating the threat of terrorism, despite paving the way for the data to be used for a much wider variety of purposes.

“The purpose was said to be able to catch the worst terrorists and criminals. It was presented like ‘if you don’t want this technology, you don’t want the terrorists to be caught’,” he said.

While acknowledging the example of how China is using facial recognition as part of its dystopian social credit system, Santow cautioned against believing these fears apply only to authoritarian regimes.

“I don’t want to become fixated on the example of China, because we know in many other liberal democracies we know the use of facial recognition technology is growing, and being used to carry out high-stakes decision-making,” he said.

To protect Australians against harm from technology that’s already being used now, Santow says, there needs to be comprehensive reform to Australia’s privacy laws that haven’t happened for more than a decade.

Santow, who is set to finish up as commissioner at the end of the month, noted the ongoing Privacy Act review but urged further action.

“The problem is this: we have data protection laws but we don’t have proper laws for our personal privacy rights. We need to have stronger, broader protections in place,” he said.

What do you think? Are you concerned we could be heading into mass surveillance? Share your thoughts with us by writing to letters@crikey.com.au, and include your full name if you’d like to be considered for publication.

The police state began under John Howard but took off at a sprint under Abbott. The CONServative arm of the Coalition found fear and division worked well under Howard. They have embraced it ever since and wedge Labor every chance they get. What’s worse is Labor follow like lambs to the slaughter instead of taking a stand against them.

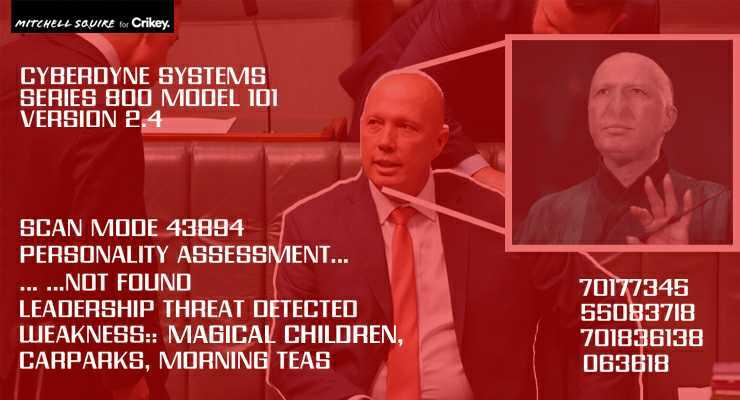

With a federal election in the near future expect to see Peter Dutton beating the drums of war loudly, whilst other dastardly scenarios will be thrown about, sending older Australians into conniptions until the election is over and nothing untoward occurs. People are so gullible. They fall for the Coalition’s scare campaigns/BS every time.

Conservatives have an enlarged amygdala they’re still carrying clubs.

Research suggests that conservatives are, on average, more susceptible to fear than those who identify themselves as liberals. Looking at MRIs of a large sample of young adults last year, researchers at University College London discovered that “greater conservatism was associated with increased volume of the right amygdala”.

The amygdala is an ancient brain structure that’s activated during states of fear and anxiety. (The researchers also found that “greater progressiveness was associated with increased gray matter volume in the anterior cingulate cortex” – a region in the brain that is believed to help people manage complexity.)

that explains everything.

Dutton wants us to be a PoliceState with him calling the shots.

I’ve heard 1984 is his favourite utopian book.

Looking at the two pictures he does not look the same. In the one on the right hel looks human. Perhaps it is just a ploy so he can look good with his facial recognition pictures. Would not put anything past him.

Unlikely, unless it comes as a colouring-in edition.

Even then, he’d prefer the monochromatic version.

All the restrictions on our liberty in the name of ‘combatting terrorism’ – how much of a threat does terrorism really pose in Australia? Most perpetrators picked up so far seem to be people driven more by mental health problems than ideology. Shout ‘Allah akhbar!’ as you commit your crime and you’re an instant celebrity, albeit in jail.

But wait – Crikey has today made a similar point, further down the page:

Emeritus Professor Paul Mullen — who, among other things, interviewed the perpetrators of the Port Arthur and Hoddle Street massacres — tells Crikey that notoriety was a driver for mass shooters. Only one in 10 actually had a serious mental illness. Most are pathetic loners with a death wish and a desire that their life means something, anything. They follow a “script” they see in the coverage of previous mass shootings: the shooter’s face plastered over front pages, reporters raking over old diary entries, suicide notes or manifestos, films made about the horror. By narrativising the attack, however you portray it, you play a part in fulfilling that script.

Many years ago, schools were set alight and got huge media coverage. No sure what State it was, but police asked media that no publicity be given to the arsonists, and it worked – no public news, no school fires.

Great article and thanks for the links. I would like Australia to pass a law akin to the GDPR in Europe. I won’t hold my breath with the current government but hopefully a new election will pave the way for the adults to be back in charge.

Although, should Labor win and try rolling back the most egregious security legislation, expect the Murdoch machine to go Hominoidea excreta, and perhaps the security agencies to stage a small event or two with some loud bangs. Told ya they were rolling out the welcome mat!

I just searched “what odds that ALP will win next federal election”. OMG. Start packing. The adults are MIA.

The technology is still way off being accurate, and is inherently racist. Yes, actually, unequivocally racist algorithms underlie it’s ‘learning’. Seriously, scholars who look at this have documented it.

Even one to one is dodgy. Consider your passport on leaving or returning to Australia. No spectacles allowed, look straight ahead, no smiles, don’t move, and even then the machine struggles at times.

Besides, what would an honest government want with such information anyway?

Dog

I agree, but it is a captive audience. When one enters the “Land of the Free” thee good ole USA. one is fingerprinted or checked against existing records. The USA must have a more extensive record of Aussie fingerprints than Ostralia.

Would the USA allow the Oz police to run a print match through their system? After all we all have five eyes.

In answer to your question, YES.

They do it routinely along with other wrinkles so that our authorities have (im)plausible deniability when they claim to be shocked, shocked I tell ye, that anyone would suggest they did such nefarious things.

We return the favour for the same reason, spying on US citizens when it is illegal under their own law – part of the joy of 5 Eyes. (I’ve often wonder whether there are two bioculars and a Long John Silver, with only 5 eyes between them.)

As usual, only Aotearoa refuses to go along with these evil activities.