Tuesday was a special day. It’s not every day we find out house prices rose by $157,000 over the past year. But on Tuesday, when the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released its Residential Property Price Index, the sheer scale of Australian house price growth was made evident. Average capital city dwelling prices rose a whopping 16.8%. That’s not quite cryptocurrency levels of return, but it’s close.

In the pandemic, we have learned a lot about what drives property prices. Old arguments about migration causing property price rises need to be shelved — or at least very much nuanced. Because the single biggest moving part in the past 18 months has been interest rates. Official interest rates fell to basically zero, and mortgage interest rates followed them down.

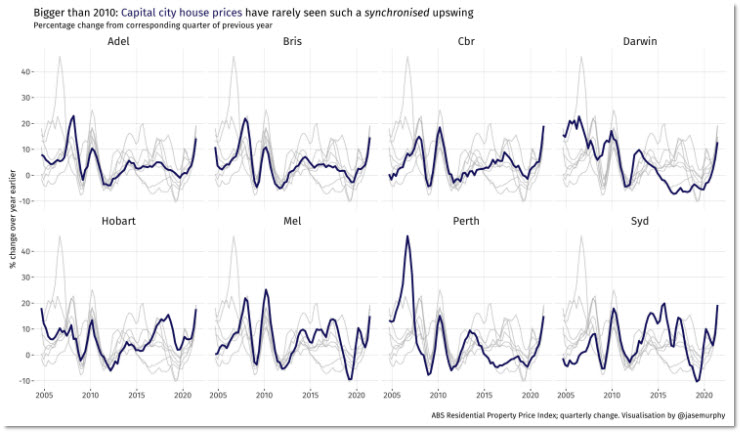

As the next graph shows, that lit a fire under house prices in every capital city. Darwin to Hobart, no city has been left behind.

You can borrow a million bucks to buy a home at less than 2% interest. That makes it easy for people to take on staggering mortgages. And Aussies are doing so. Well, some Aussies are. Not all age brackets can afford it. The level of home ownership in Australia for under-40s has been at its lowest point on record.

Should the Reserve Bank (RBA) bear the blame for all this? Not if you ask the RBA.

On Tuesday, as the new ABS house price data was being released, two RBA officials made themselves available for questioning. First up was assistant governor (economic) Luci Ellis. She was keen to point out changes in the housing people want.

“In the wake of COVID, many households have reconsidered their housing needs,” Ellis said. “Some people have considered whether moving to a regional area or to an outer part of a large city is now more practicable because working from home is more practicable, and because living in high density areas is something they don’t want to take on as a health risk.“

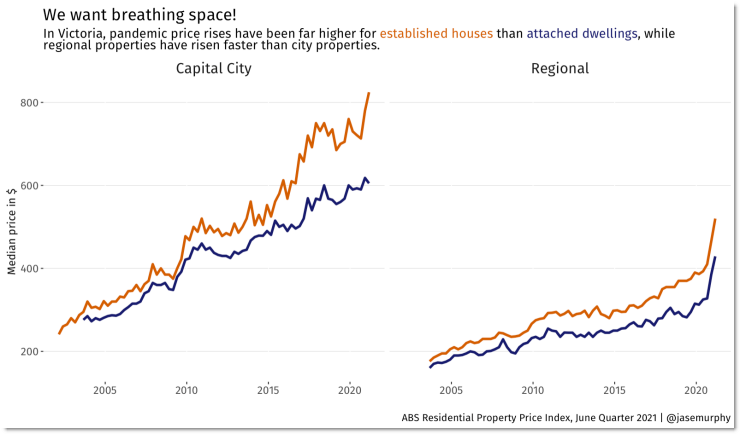

Ellis is not wrong. While every state has seen price rises, not all types of property are equally desirable. As the next graph shows, if you own an inner-city apartment in Melbourne, all this chat about rising property prices might leave you cold. The winning move has been owning regional property.

With apartment blocks in Melbourne regularly being declared as Tier 1 exposure sites, such a shift is understandable.

What this tells us is that interest rates are an accelerant. Petrol on the fire. They can’t make a property’s price rise if nobody wants that property. You need demand to make prices rise. And the supply and demand dynamics for attached dwellings in the inner city have not been enough to generate big price rises.

The RBA boss was willing to concede the role of low interest rates in rising house prices.

“I know many young people are concerned … it’s true low interest rates are having an effect,” Philip Lowe said in response to a question on Tuesday. “It’s something that as a citizen I would like to see addressed; as a central banker I can’t do anything about it.”

That’s plainly untrue, but he did go on to explain what he meant. He emphasised low interest rates are in place to help the economy, and raising them to cool the property market would hurt the economy. “This is a poor trade-off,” he said.

The argument about house prices is not unlike the arguments about bushfire season. Is it the climate of low interest rates or the sparks of demand that causes the infernos of rising prices? The answer is one that requires minds capable of grasping nuance: both.

Low rates make house price surges more likely, but they’re not solely and uniquely to blame. You can’t have a fire without a spark, and you don’t get a house price boom without supply and demand dynamics making it happen.

So long as Australia’s economy is underperforming, with low wages growth and higher-than-desirable unemployment, we will have low interest rates, and that will mean surges in supply and demand for property cause big price changes.

So what will happen next with demand? One scenario is that the borders open back up in 2022 and the international students return just as COVID fears abate. That could cause a strong pull back to the centre, with city prices rising.

Alternatively, supply could become the relevant factor.

“The growth rate of the dwelling stock has for some years run ahead of population growth,” Ellis said on Tuesday. The government’s HomeBuilder program has also led to a supply bump. Could Australians become sated with housing? Perhaps not exactly, but equally, the growth rate of the last year looks extremely hard to maintain.

Should the Reserve Bank (RBA) bear the blame for all this? Not if you ask the RBA.

Given that the RBA is the maates hideout from past Liberal Party hacks and henchmen, from banks, tax haven users, Panama Paper fugitives, big business, the Big Four tax evasion audit firms, no one should be surprised.

I believe another reason for the huge increase in interest in both Tassie and NZ real estate is because of climate change predictions, that the mainland will become a shrinking desert, but Tassie and NZ will actually end up with milder conditions even more suited to food production.

Move to places that haven’t been spoilt yet, instead of trying to unspoil where you already are! It’s the sensible human solution. Like those billionaires eyeing off Mars. Good grief.

Splvs, pimps, touts, bludgers and urgers.How I wince when I see an article in the MSM about some bright young thing who has amassed a portfolio of ten prperties, (note Prop-er-tees, not houses, don’t you know).it’s monstrous I know, but the great unwashed had their chance at the lst election and rejected any control over negative gearing, the most pernicious tax-avoiding racket ever.evolved.

It always mystified me that the BRW annual Rich List was not considered a condemnation, like the old tabloid header “We Name the Guilty!”.

In Japan there is stiff competition to be top of the tax paying list which is published to great acclaim & approbation.

Imagine that happening here!

Or the Capital Gains Discount

Good example other day in Domain reported by SQM real estate research claiming in nominal terms a massive capital gain for Kylie who sold her Armadale (Malvern/Mel.), after purchasing in 1990 for $180k sold recently for $1.7million making a ‘profit’ or capital gain of $1.5 million…. with an expected weekly rental of (only) $700.

Apply a 7% benchmark for real value, compounding from $180k from 1990 would become $1.5 million anyway; treading water?

Further, using $700 p.w. (annual income at 7%) would make fair value only $520k….. something out of whack with the property market with massive divergence between income and asset values, unless negatively geared.

‘The growth rate of the dwelling stock has for some years run ahead of population growth’ is an utterly meaningless statement when nationwide the supply is many hundreds of thousands below demand. We can easily see that the cost per square metre of building isn’t much different from the 70s. It would be even less with medium density dwellings. We urgently need more land releases and a change of building codes so that 2 to 4 story housing can be built in or near to town centres. The average Aussie town centre is extremely boring and empty after 5.30pm. Compare that with the way most of the the rest of the world lives. In town living would revitalise 99% of country towns. Rental regulation reform would also help enormously in making in town living affordable.

On the Continent, apart from the capitals, there are very few cities over a million (the 3 H’s of northern Germany for historical reasons preVerbindungen) but many hundreds with around the optimum 100K.

A good example was Bonn when it was capital of the BDR for almost 50yrs – market gardens, thriving unis & tech colleges [all had purpose built Studentheims de rigueur], abundant small factories, theatres and the ubiquitous ‘colonies’ (allotments).

In Stuttgart there was a hill of vines across the road from the main train station, a park of several hundred acres between the main shopping CBD and the residential areas and the main factory for a well know car…can’t remember the brand name offhand.

Australia has two megapolises with half the national population, dormitory suburbs hours away from sources of employment and an empty interior.

Work from home has come out of nowhere and will be a huge lift to people who want to work regionally. There is now less reason to live with in easy commute of the CBDs.

Such common sense.

My family is going to have transport issues in the next decade or so and I can’t afford to live in the spacious properties near town. I need to be walking distance to things in the future. I am a sociable person and would go out and spend money in town if I could get there more easily.

I work in the town centre and we are can only justify opening Thurs, Fri, Sat nights. As an alcohol based business in a town with no Uber the driving thing is an issue. I used to live in the inner city and the walkability was a huge factor in people going out.