This article is part five in a series. For the full series, go here.

Some readers may find aspects of this article distressing.

Like many of those placed under a guardianship order, Janine’s* story starts in hospital. She thought she’d be in there for a few nights. She had no idea she might never go home and could face losing her assets to state control.

Janine is in her 70s and lived in a rented apartment in Tasmania with her adult son. She raised money for a charity several days a week. She uses a wheelchair for a pre-existing condition but that hasn’t stopped her from travelling around the country in her campervan, chatting to locals and living life to the fullest.

Janine says she is competent, sound of mind and should be able to continue living her life as she always has — freely. But she is not free. She is under an order that restricts most of the decisions about her life.

Earlier this year, Janine hurt her back, limiting the use of her leg. After two months in the hospital’s rehabilitation centre, she decided she could manage her pain at home. She assumed, like other times she’d been in hospital, she would talk to the doctors and be on her way.

But before she could discharge herself, a doctor applied for an emergency order for state guardianship, arguing Janine didn’t have the mental capacity to look after herself or her finances. The order was sudden and incredibly shocking.

“It’s patronising and insulting,” she said.

Janine says she had a short consultation with medical staff — in which she says she didn’t realise she was being assessed — and was diagnosed with dementia.

A virtual tribunal hearing with the office of the public guardian was held in the rehabilitation centre. Janine says she didn’t realise its significance and didn’t put her case forward clearly.

She also says the tribunal asked her only one question — about her injury — and the decision was made in under an hour to place her care decisions in the hands of a public guardian, and her finances in the hands of the public trustee.

“As far as I’m concerned I have all my faculties,” Janine told Crikey. “I’m a fundraiser and I’ve been doing it for quite a few years, so I’m managing money all the time.” She declined to provide documents to Crikey because she feared she could be found in contempt of court.

Although there are legitimate reasons for elderly people to be placed under guardianship orders — social workers and medical staff are trained to look out for signs of elder abuse — there’s also a darker incentive: generate revenue and reduce the burden on state hospitals by fast-tracking people into aged care.

‘I’ve been imprisoned in rehab’

Once the guardianship order passed, Janine wasn’t able to leave the rehabilitation centre for six months. She couldn’t access her funds and says the state public trustee attempted to sell her assets, including her campervan. Her apartment rental lease lapsed, and her son had to move her belongings into her van.

“I’ve been imprisoned in rehab,” she said. “I don’t have any access to my money. I do a lot of reading but a book doesn’t last me long and when you sit here for so long, you forget things. It’s very depressing and very frustrating.”

When Janine was finally able to leave she checked into short-term accommodation and started looking for long-term accommodation, but she was soon placed back in hospital because the guardian deemed her accommodation unsuitable. She says she lost thousands of dollars in prepaid accommodation.

Janine knows the ordeal has been expensive, but repeated requests for itemised invoices for how much she is being charged by the state have been ignored. She says the guardian continued to organise support services such as cleaning even when Janine cancelled them because she was capable of looking after herself.

The guardian is now attempting to place her into residential aged care.

In the last financial year, Tasmanian public guardians were granted powers to decide where half the state’s 310 clients would live.

Counting the cost

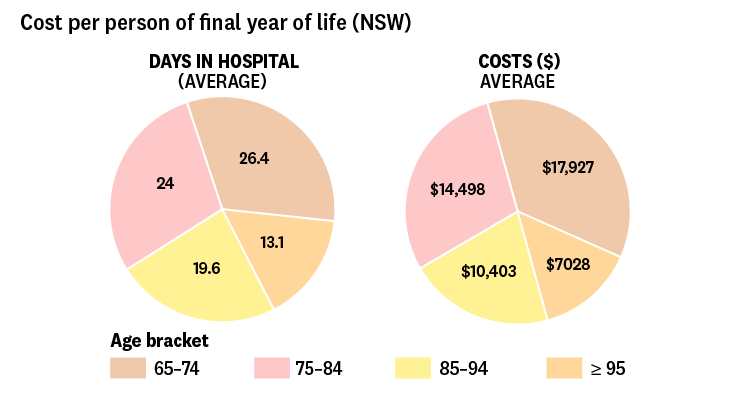

There are incentives for hospitals to support guardianship orders. In New South Wales, a 2007 study found care of people aged 65 and over in their last year of life accounted for 8.9% of all hospital inpatient costs, and average inpatient costs rose from $646 a person in the sixth month before their death to $5545 in their final month.

Australia ranks 19th out of 20 OECD nations for people over 65 dying in their own home and has the eighth highest healthcare expenditure of GDP out of 36 OECD countries. Australia had 3.8 hospital beds per 1000 population, compared with the OECD average of 4.7.

Aged and Disability Advocacy Australia’s chief executive officer Geoff Rowe tells Crikey the system was used to “fast-track” elderly people into residential aged care.

When a resident has a minor injury in a residential aged care facility, instead of being admitted to hospital GPs are called. The federal government covers residential aged care costs and the state covers most public hospital costs. Elderly people have to be assessed in their homes to be eligible for Commonwealth-funded home care, which can have delays.

Bedside hearings increasing

Applications and tribunal hearings where a judge decides — based on evidence from social workers, family and medical practitioners — whether someone’s care and assets should be managed by the state are increasingly happening in hospitals instead of courtrooms.

Queensland’s hospital hearing pilot program, run across four Brisbane hospitals, reduced the period between filing an application to a tribunal decision being made from an average of 13-14 weeks to three weeks. More funding has allowed an extra 320 applications to be heard at hospitals annually.

“At times, tribunals are being held without the person being aware and decisions are being made where a person’s illness might be transient,” Rowe said.

A particular concern is around elderly people who have temporary delirium — often caused by urinary tract infections — but who soon recover with antibiotic treatment.

“They returned to normal and they literally wake up and find themselves in residential aged care,” Rowe said.

Advocacy Tasmania CEO Leanne Groombridge tells Crikey Tasmania has the oldest guardianship laws in the country which actively removes the rights of those with disabilities.

“What might be a temporary illness can become an involuntary move to aged care, being detained in hospital, losing your legal right to make decisions about your life, having all your personal and emotional belongings sold, having no one actually explain what is happening to you, and having no chance to tell your story,” she said.

“People’s choices and views are not heard or respected. These denials happen across Tasmania in hospitals, services, through our legal systems, and in our society.”

Janine is furious about her disempowerment and says her wishes have been ignored.

“I make decisions and the guardian just overrides them,” she said. “There’s no consultation. She thinks she’s helping me, but she’s just hindering me.”

A spokesperson from Tasmania’s public trustee told Crikey: “There is currently an independent review of the public trustee underway and we are not in a position to comment until after that process is complete.”

Tasmania’s public guardian didn’t respond to Crikey’s request for comment, but The Australian Guardianship and Administration Council (AGAC) which represents state and territory government guardian and trustee agencies said the guardians’ role in some states is to make decisions that are in the best interests of the person they represent.

“In other states their decision-making is based on the person’s views, wishes and preferences,” the spokesperson said.

“When making decisions as either guardian or manager/administrator, public advocates/guardians/trustees are guided by national standards for public guardianship and management developed by AGAC.”

*Name changed for privacy.

To read more pieces in this series, go here.

For legal reasons, please don’t identify yourself or others under guardianship or financial administration in the comments.

Frightening. What does her son make of all this?

Hmm. I have seen some weird things in some hospitals in various departments regarding mental health in mental health units and with the aged care in general medical sections. When a migrant Dr with poor English asks people about their understanding of space and time. The reply can be not what the Dr is expecting. The Drs poor comprehension can impact on what happens to the person. I have seen exactly this scenario. It’s heartbreaking. And yes, family can muddy the process with their own agendas.

I find all these stories about guardianship have a biased slant. What they have left out of the stories, although you get a hint, are the underlying fights within the relevant families that lead to requests to appoint a guardian in the first place.

Yes, such fights exist, between family members and with ‘the authorities’. But there are many times where the situation is quite clear regarding family members, e.g. it is easy to see and prove those who have earnt the right and responsibility of being guardian etc through their previous and continuing excellent treatment of the person involved, then some distant relative comes ‘out of the woodwork’ to contest it with all signs of previous neglect of that person in need. If a suitable family member or other familiar responsible adult is available or if power of guardianship and power of attorney agreements are in place, their rights to guardianship etc should FAR exceed the possibility of these officious government employees/appointees being appointed. These public bodies should only be needed when it truly is a “last resort” situation!

This is quite separate from the legitimate role of these bodies to protect relevant individuals at risk. And in fact deprives the needy person of that protection, by combining the 2 sets of functions in one pair of hands!

I have been a nurse in the public system for over 20 years and have never even heard of a doctor getting a patient placed under the guardian in order to get them out of hospital. Further, as an ED nurse I can tell you lots of Aged Care Homes send patients to ED for minor injuries as it’s faster than getting a GP out., if a GP will call out to the home, and not tell the staff to send the resident to ED. Placing people in Aged Care is not a panacea, especially as you can wait months for a nursing home place.

Do you have any evidence, apart from what an elderly patient diagnosed with dementia tells you? Having looked after countless such patients I can assure you that many of them are not your caricature of someone with dementia.

This reads like a smear campaign without offering any evidence. Have you sat down with thus lady for an extended conversation? I will bet money that you did not have someone assess her professionally for dementia.