Trending

Let’s do a role-play. It’s the 1960s. You’re the US surgeon general Luther Terry and you’ve got this sneaking suspicion that smoking might just be unhealthy.

So you come speak to me, Mr Philip Morris, to find out what I have to say about it. “Smoking is fine,” I coo. “Ignore the fearmongers, junk scientists and haters. Our data shows smokers are just as healthy as non-smokers. But don’t take my word for it: speak to this scientist whose research we’ve supported.”

Would you believe me? Probably not. Or at least, it would be foolish to do so.

And yet we take the word of a company with a product that’s been blamed for playing a role in genocide, in radicalisation, in interfering in elections: Facebook.

Two-thirds of Australians use Facebook. Millions more use the company’s other products Instagram and WhatsApp. We use them to socialise, to organise and to get informed. Companies, political parties and (as shown during the pandemic) even governments depend on it.

Over the past few weeks, the tech giant has been in its “biggest crisis since Cambridge Analytica”, according to US tech journalist Casey Newton. The Wall Street Journal’s bombshell Facebook Files investigation shows how Facebook privately knows but has failed to address how its service is hurting people in a variety of different ways. (I really cannot recommend it enough, it’s so comprehensive it’s hard to even sum up without yakking too long).

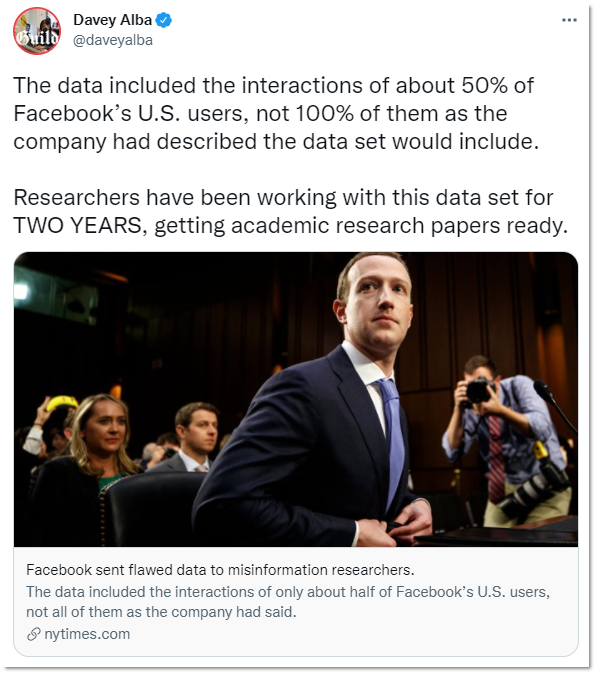

One of the reasons this investigation is so explosive is that the product itself is a complete blackbox. We can’t see how it works. The only information we have about it comes from the tech giant itself: they publish reports on a few carefully chosen metrics like how much hate speech they take down (31.5 million pieces of content last quarter!) or the top viewed posts by US users. The only other way to understand what’s happening on this platform is through janky workarounds from third parties that soon get shutdown by Facebook.

It’s clear from the company’s behaviour that we can’t just trust them to tell us the truth in a timely fashion (and sometimes even what they tell us can’t be trusted).

And it’s clear that there needs to be an informed public conversation about how they’re influencing the lives of Australians.

That’s why the federal government needs to force Facebook to give us data. There’s specific information that we could legislate them into providing:

- An Australian-specific edition of the most viewed posts

- A database of all Facebook advertisements, who they’re targeted at and how much has been spent promoting them

- How many people saw pieces of misinformation before they were removed

Additionally, a proposal from tech policy group Reset Australia would have Facebook publish a constantly updated list of the most popular COVID-19-related URLS on the platform to help track misinformation.

Or it could be a wider net. We could force Facebook to provide broad data sets about Australians for policy development or analysis by independent researchers.

We got close to something like this recently. The original news media bargaining code legislation required Facebook and Google to give news publishers insight into how their algorithms worked. It didn’t make it into the final law, but it is possible. And because this isn’t about the algorithm — their secret sauce — demanding data can be done without revealing all of Facebook’s commercial secrets.

I’m picking Facebook because they’re the biggest player but there’s no reason this shouldn’t apply to other social networks too. Such a law could require any platform with more than a certain number of users — one million, perhaps — to provide this kind of information. There’s not really any other downsides, other than the cost to platforms that are lightly regulated.

Our data is our story. Although it’s collected by Facebook, it’s about us. Australians should stop waiting for Mark Zuckerberg to volunteer information about our lives, spun in a way that best suits him. We must take it ourselves.

Hyperlinks

We found the PM’s Facebook and Instagram accounts. That’s a national security risk

This was a couple of months in the making, but finally I had enough proof to definitely say I found Scott Morrison’s personal, private social media accounts. And if this humble internet reporter can find them, imagine what more nefarious, intelligent actors could find out… (Crikey)

Fears adult content and sex workers will be forced offline under new Australian tech industry code

Although the Online Safety Act was passed, its powers are yet to go into force. There’s concerns that its implementation could chase sex workers offline. (The Guardian)

‘A lightning rod for the disaffected’: TGA staff receive death threats and abusive messages

When we talk about the impact of social media campaigns by anti-vaxxers, it can often feel divorced from real world impact. Here’s how these things actually harm innocent people. (The New Daily)

ASIC issues stern warning about social media pump and dump posts

It’s getting increasingly difficult to tell what is and isn’t authentic behaviour online due to the power of influencers to command the attention and direct activity. When it comes to trading, it can get very complicated. (SMH)

Real Rukshan: the live streamer who took Melbourne’s protest to the world stage

Here’s my deep dive on someone who emerged as the unlikely central character of Melbourne’s recent anti-vaccine mandate protests. (Crikey)

Content Corner

One of the biggest stories in the world last week was about the disappearance of Gabby Petito. The young woman was found murdered in a Wyoming national forest after nearly a month of looking.

What made this tragic case distinctive was how communities on platforms like TikTok and Instagram popped up around the story, searching for clues in Petito’s online wake.

“While Petito’s family were desperately looking and hoping that a beloved member of their family was found safe, people on TikTok were picking apart every minute detail about the missing influencer and her last known movements,” Michelle Rennex wrote in Junkee.

When I caught up on the coverage of last week, a lightbulb went off in my head because I’d already seen the same thing happen in Australia.

The case of missing boy AJ Elfalak is one that has a happy ending, thankfully. The three-year-old was reunited with his family after being lost for three days in the NSW bush.

But some strange media moments led TikTok users to begin creating videos claiming that the family was suspicious.

People began to dissect footage, even spreading unfounded theories.

What this shows is that this isn’t just a Gabby Petito-specific phenomenon. With a culture primed by true crime media combined with the memetic, algorithmic engine of platforms like TikTok, we’re going to see ad hoc communities pop up around every high profile case like this from now on.

Sometimes, they could help like they did with Petito. In other instances, like in the case of the Reddit crowd investigation that wrongly identified a recent suicide victim as the Boston Bomber, it will often be wrong.

Here’s my awful, gruesome prediction that makes me feel depressed even thinking about it: true crime creators will get better and better at hopping on new cases. Like when a new season of Fortnite premieres or when a new game comes out, creators jump on them for clout and money, before ditching them for the next case. It’ll almost be speculative: get on a case early and you could become the authoritative voice, with all the benefits that entails.

Let’s hope I’m wrong!

After years of pleads and suggestions it seems evident that the sole thing that will address the pubiic harm social media platforms do is money. Make them liable for the effects of what they publish and suits will prompt action. I’ve mused that after decades of lawyer jokes there but for lawyers (or their ethics commitees that can deregister as one author posited) went US democracy and it seems only they can rid us of social media toxicity.

It’s deeply concerning that the other story you alluded to went viral as it can only lead to copycats sigh. I’ve long wondered if the first school shooting hadn’t received media coverage if there would have been more. Bandura’s social learning theory demostrates that humans do copycat behaviors they see.