If your end-of-year celebrations traditionally involve French Champagne, Chinese toys or Korean electronics, look out. Global shipping is trapped in a worsening spiral of delays and capacity shortfalls that could leave consumers hunting desperately for local alternatives to their favoured imported goods.

Welcome to the inaugural instalment of Crikey’s Shipping News, where reports are grim and the forecast is dire. When the Suez Canal was blocked by the container ship Ever Given in March 2021, that was apparently just a foreshock. The full seismic effect of global disruption on the movement of goods around the globe is only now being felt.

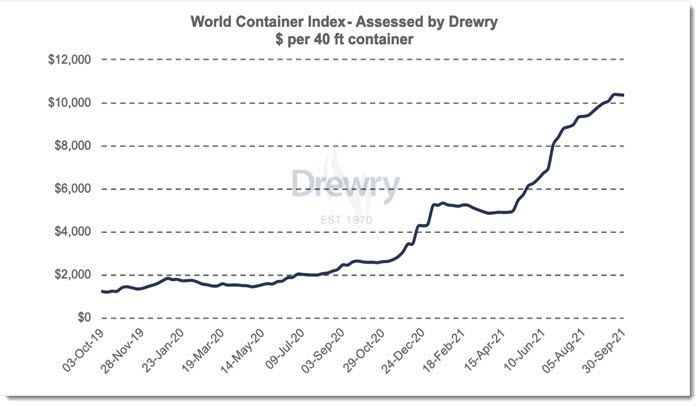

To see the simplest version of the story, let’s look at the price of containerised trade. Sending a 40-foot (13-metre) shipping container around the world used to be pretty cheap: about $1910. Now the price is about 7.5 times higher: about $14,160. That’s an enormous increment when you consider that choices about whether to trade overseas can be based on margins of just a few per cent.

A lot of exports are simply not going to hit the high seas at these prices. And that’s part of the point of high prices. There’s not space for every export to go, some need to be squeezed out.

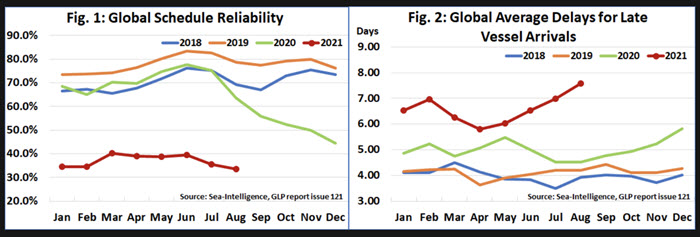

The capacity issues are real. As the next chart shows, ship delays are endemic now and delays are roughly twice the usual length for this time of year.

Reliability is the lowest on record, according to sea-intelligence.com.

The largest port in North America is Los Angeles. There, an estimated half-million containers are waiting to be unloaded and ships are waiting an estimated 10 days to get to dock.

Port of Los Angeles CEO Gene Seroka blamed record factory production in Asia and booming buying power in America.

“It’s like taking 10 lanes of freeway traffic and moving them into five,” he told CNN last week.

Delays outside ports mean fewer containers are available on shore where they can be filled, contributing to escalating delays. A similar story is found in all the world’s major ports. The world’s biggest container shipping company, Maersk, is now cancelling some services.

“Congestion in Asia and Oceania ports continues to put pressure on vessel schedules, resulting in … missed sailings, which further exacerbates capacity availability,” the Netherlands-based company said in a recent update to clients.

Outside the box

Companies who would usually use container shipping are hunting for alternatives. Coca-Cola is now shipping some of its raw ingredients in bulk ships, the kind that would usually carry ores and grain. Meanwhile, demand for new container ships is off the hook and far fewer ships are being retired. (That would be bad news for the famous ship breaking industry of India if they weren’t choking on an endless supply of unwanted cruise ships right now!)

In the Port of Melbourne, Australia’s largest port, shipping issues are exacerbated by recent industrial action. The union called off that action this week, but only after the port’s operation was threatened by over 100 wharfies being forced to isolate after exposure to coronavirus.

It may seem like a miracle anything is arriving by ship at all at the moment, but some things are arriving in large numbers. Australia imported $2.5 billion worth of cars in August alone, a new record number for a single month. Cars don’t arrive by container, they come on dedicated boats called RoRo (Roll-On, Roll-Off). If you’ve ever wondered why a new car has a few kilometres on the clock, this may be why: Each new car is driven onboard the ship by a professional (in this video you can see them driving in, parking together tightly and being driven out of the ship again by minivan.)

But cars are high-margin. Not everywhere is getting the ships they need. “Our services are omitting some ports in Asia and Oceania to protect vessel calls at key origin and destination ports,” said Maersk.

In Australia, one shipping line just skipped Fremantle, meaning a lot of agricultural machinery now needs to be transported back across the Nullarbor to get to the WA farmers who need it. Such moves help sea transport to catch up, but only by placing more stress on land transport. And we can’t forget it was a shortage of trucks and truck drivers that led to the ongoing UK petrol shortage.

It seems highly likely more shortages will crop up before Christmas. If there are imported products you can’t live without, best buy them now.

“Meanwhile… far fewer ships are being retired.”

That’s not merely an issue for the ship breakers. These ships are seldom retired until the structure, the machinery, and all that is necessary for safe and reliable operation are thoroughly worn out. So it would be interesting to know just how they are being certified as fit to continuing operation by their independent Certifying Authorities. Are the ships being refitted to bring them up to scratch? Or just held together with duct tape?

So will there be a significant rise in shipping ‘accidents’ and sinkings? We might not notice since these incidents are often not seen as newsworthy. It’s all out of sight, out of mind, and the crews on these vessels are often from countries that don’t interest us much.

How appropriate that you should be first to comment here SSR!

I live in a place with a busy shipping port all around me. It is interesting to see that the “certifying authorities” for shipping all seem to be in third world countries and tax havens. Why is that?

I think you are confusing the CAs with the flag country. The former conduct engineering surveys to determine if the vessel is sea-worthy. None of the CAs are based in third world countries. There are only about six, including Lloyd’s Register (LR), the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) and Det Norske Veritas (DNV).

In this issue of Crikey we have one article bemoaning the “fetishism for manufacturing” by the major political parties, and then this article discussing the problems occurring in international shipping.

It would seem obvious that a country with little or no local manufacturing capability would be extremely vulnerable to this sort of shipping disruption.

Some pathetic ‘buy local’ campaign is not remotely going to make a dent in Australia’s reliance on imports. Even if Australia somehow did restart eg car manufacturing (in the face of all common sense IMO, but anyway), there is no way that all the inputs will be locally sourced. If you don’t want to go back to a 1930s lifestyle, there’s no way out of reliance on imports.

So you don’t reckon we have all the local materials required to build cheap electric vehicles that have interchangeable batteries?

I reckon we’d go pretty damn close. The only thing holding us back is the political will.

We can have imports.. it’s just that we should rely on them.

Great new segment for the show. I’m up for any infrastructure and logistics news (with a sustainability angle please) 🙂

And some discussion about ways to deal with the tyranny of distance while being more sustainable. We should be at the forefront of innovation, yet we seem to fail. Bagging out the Inland Rail (because of the obvious Coal Alignment until nobody wants our coal), yet not offering an alternative to getting more and more freight around seems counterintuitive.

Assume its due to climate change, but large increase in containers being lost due to bad weather. Polluting the oceans as well as coasts when items washed up. Sorry can’t recall the site.

Jason, we are really behind the times in Oz, when you think about it.

New York Times has been reporting on this issue for months, actually not long after the Suez canal blockage.

Ports in several countries have been closed for up to six weeks at a time, due to one ship having an outbreak of Covid, holding up a large succession of others awaiting berth.

Or ,if those on the ships are not sick, workers in Ports have been – again causing a Domino effect….and so on and so forth.

The US president has recently cited this ongoing problem as one of the reasons he’s pushing ahead with his “Made in America” plan, initially a concept of Trump’s (who’d have thought he’d actually think up something meaningful?).

But it’s good that here in Australia, the media is finally catching on and giving everyone a heads up.