Long lines at UK petrol stations and blackouts rolling across China seem far away from our experience here in Australia. We are rich in solar energy and abundant in brown coal; we pump more gas than anyone. But the northern hemisphere’s energy crisis could send shockwaves in our direction, and could even be the harbinger of an enemy long forgotten – inflation.

The price of energy feeds into the global economy in many ways, and when oil, coal and gas prices are all rising at once, that lifts prices in many industries. In coming weeks, petrol prices at the pump are likely to hit new records as oil has risen to over $80 a barrel. According to the fuel price website petrolspy.com.au, Sydney’s average price for unleaded petrol (U91 with 10% ethanol) is $1.74 a litre and the cycle is still rising. Could this be the fuel price cycle where prices pop over $2 a litre?

The price of oil briefly went negative during the early days of the pandemic and it lingered around $25 a barrel for a while. But now amid a surge in demand Brent crude oil is selling for over $80 a barrel, the highest level since 2014 (when OPEC collapsed). That is also pushing up natural gas prices. Spot prices for gas in Japan and Korea have risen nearly four-fold. Keeping warm this northern hemisphere winter is going to be expensive.

Anything made using energy — be it manufacturing or construction — is likely to get more expensive. Gas also feeds into fertiliser production. So it is no surprise the price of fertiliser has hit its highest point on record, as the next graph shows.

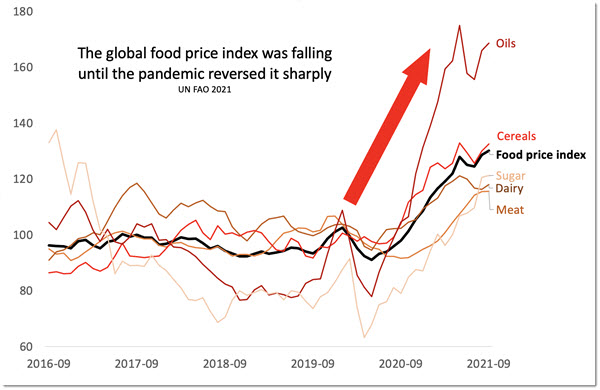

But farmers aren’t sweating this price rise because they are making hay on the other side. The price of what they sell has also gone bananas. The UN’s food and agricultural organisation (FAO) keeps an index of international food prices, shown in the next graph. Price pressure might not be showing up yet in the local shops but it has certainly hit the global markets where food trades as a commodity.

Almost everywhere we look we can find input price pressures. Lumber prices have been ridiculous for well over a year now. Coffee is supposedly going to be in shortage. Beef already costs far more than it did a few years ago.

Australia is not in nearly so bad a position as some other countries, because we sell a lot of these things. Coal, gas, beef — these are all things that fatten the Australian purse when their prices rise. Farmers win, mining shareholders win, and the federal government wins via tax receipts. But a whopping current account surplus doesn’t keep prices down at the shops. And that’s why we need to keep an eye on inflation.

Australia slew the inflation dragon a long time ago. Its skin has shrivelled up and its scales blown away on the wind like dust. A generation is rising for whom inflation is a mythical beast, a fairytale. But they might be about to get a taste of its hot breath.

The RBA is still forecasting low inflation. “In underlying terms, inflation is expected to be 1.75% over 2022 and 2.25% over 2023,” governor Philip Lowe said in August. The RBA continues to have in place policies designed to rev the economy up. Those policies are warranted given the economic destruction of the recent Delta waves. But how fast can the RBA react if inflation proves to be more than transitory?

Australia saw a big fall in inflation in 2020 and a big lift in inflation in 2021 as prices went back to normal. The question is whether we settle back into the low inflation groove. In America, the US Federal Reserve is considering raising interest rates as soon as 2022, to try to prevent inflation from frothing over too much.

The RBA has admitted global events are a major input to its interest rate settings. Is it possible the bank could renege on its plan not to raise rates until 2024? If it does, it won’t be politically neutral. Higher petrol prices and higher interest rates could create a very displeased Australian population.

Just shows the free market (and adversarial multi-party democracies) can’t engender an orderly, timely transition to green.

The global roll-out of solar/wind in free markets is too slow, resisted by fossil companies addicted to big profits; and the necessity for governments to subsidize renewables plus storage – which is still more expensive than coal – is a political non-starter because orthodox economists are still peddling their debt and deficit ideology, which requires interest rates to rise, to deal with inflation caused by temporary supply and demand bottlenecks. Result; recession.

Chris Richardson, Danny Price, Richard Holden and all the other orthodox economists – who are really only micro-economists serving individual businesses – ought to admit they are part of the problem, when faced with global economic phenomena of climate change and pandemic-related supply-chain disruptions.

They could learn from Ross Gittins, who is more willing to look at heterodox solutions

ROSS GITTINS: Funding the budget by printing money is closer than you think

And Stephanie Kelton’s best-seller: ‘The Deficit Myth’.

The Yanks say “lumber”, we say “timber”.

Looking at it more broadly, food price rises are a recipe for social upheaval.

True enough, French Revolution and Russian revolution of 1905 to name two big ones.

“A hungry mob is a dangerous mob.”

Article is about energy fuels. What I find fascinating is the non reporting on TV news of current climate extreme events and how they will affect world trade and economics. For instance, the Greek Island with recent fires has now been devastated by extreme rainfall. More fires in California. The two – climate and energy coming together – what is our future?

“” …. abundant in brown coal”

? Why highlight brown coal – we are better known for our abundance of black coal

Victorian versus NSW perspective? From a climate point of view, of course the prices of these fossil fuels can’t rise fast enough or further enough. This will make renewable investments more attractive. However, in the short term it may also stimulate demands for more investments and taxpayer subsidies to increase the flow of fossil fuels. Expect their lobbyists and Coalition politicians to jump on board this one.

in the end, no doubt ordinary taxpayers will bear the brunt, in prices paid and subsidies given. However, given this will occur (is occurring) it would be better if the money spent contributed to their children having a slightly less worse atmosphere than Coalition policy intends to deliver. Thus better to subsidise the renewables or at least leave it to the market, which will do much of the job if it’s allowed to.