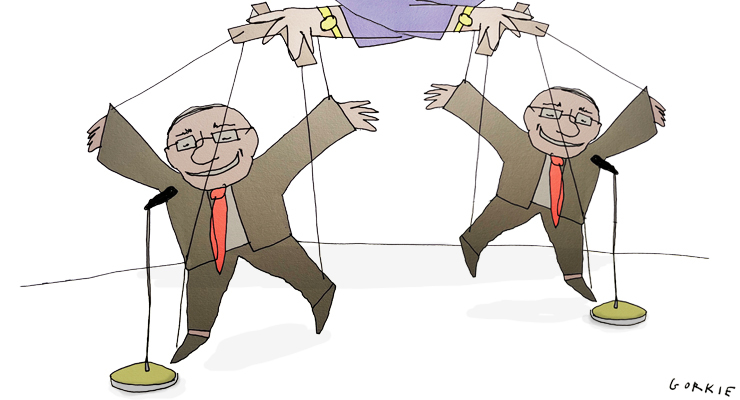

If you didn’t think Australian democracy was dysfunctional before this week (where have you been?) you have no legitimate basis for doubt now.

In Canberra a small rump of climate denialists resisted even a token climate policy unless they were handed billions in porkbarrelling. And the government blocked an inquiry into how a minister could seriously claim it was fine to accept personal gifts worth hundreds of thousands of dollars from anonymous sources.

In Sydney, a former premier described his shock at the failure of his successor to undertake the most basic governance requirements around millions of dollars in grants while occupying the position of state treasurer. In Victoria, the IBAC hearings into the squalid, disgraceful Victorian Labor Party rolled on. There was also the minor matter of two corrupt NSW Labor ministers being sentenced to prison for their crimes in the 2000s.

The upside, if there was one, is that at the state level, politicians face some kind of accountability for their egregious misconduct. Not the faux-accountability of the media conference or the parliamentary proceeding, but that of an empowered independent integrity body. One of the characteristics of the week was the contrast between politicians or former politicians and staffers appearing before integrity bodies and their usual performance in the media or parliament. In the witness box, there’s no ignoring questions, or rejecting their premise, or refusing to answer them; none of the tricks of the media trade are available. And what a difference it makes.

Even so, there’s an element of luck to that. IBAC is only probing the weeping sore of the Andrews government because federal MP Anthony Byrne decided corruption inside his own party was a hill to die on. In NSW, ICAC has only ended up focusing on Gladys Berejiklian because Daryl Maguire’s conduct was so egregiously crooked it began wiretapping him. And, of course, in Canberra there is no integrity body to investigate the widespread, indeed almost systematic, corruption of the Morrison government.

Each of the scandals demonstrates design features of our democracy that make post-fact anti-corruption bodies necessary.

For example, we allow influential interests and the very wealthy to buy access to and influence over decisionmakers. Fossil fuel companies continue to dictate the terms of the climate debate in Australian politics, with the pantomime of the government’s 2050 target really a struggle between two parties heavily reliant on fossil fuel donations to determine what climate figleaf policy to adopt to ward off international condemnation.

We allow the process of buying and exercising access and influence to remain hidden from public view, with minimal disclosure rules — and even fewer now that the Morrison government has announced, through its backing of Christian Porter, that anonymous personal donations are acceptable for MPs. Henceforth, why not bribe a crossbench MP to secure the passage of favourable legislation via a blind trust? There’s no reason you need ever be found out.

We still allow politicians far too much discretion with their use of electoral and ministerial resources, such that branchstacking as a virtual full-time taxpayer-funded role became a feature of the Andrews government — just as taxpayer-funded electioneering by the Victorian ALP was a feature in the “red shirts” scandal.

And branchstacking arises from the way we’ve allowed our political system to be run by hollowed-out political parties propped up by public funding, the benefits of incumbency and donations, leaving party branches as shells that can be moved around by ambitious party powerbrokers.

And the discretionary allocation of public funding — in the view of politicians across the political spectrum, the very core of democracy — remains a process riddled with partisan and, perhaps, personal self-interest, rather than a rigorous process of determining the public interest in the use of precious taxpayer funds.

Each of these features incentivises soft corruption, partisanship and porkbarrelling and the abuse of public funding — outcomes that anti-corruption bodies have to clean up afterwards if and when they come to light.

Curbing donations, subjecting interactions between public officials and private interests to much greater transparency and removing most of the discretion that politicians have in relation to funding — whether for their own office purposes or the use of grants and programs — is the only way to reduce these incentives. A federal integrity body worthy of the name is still necessary beyond that.

We have a political system that far too heavily relies on the goodwill and good faith of those within it. When malign actors come along — like the Morrison government, or Victorian Labor — the system too readily bends to misconduct and corruption. The answer is a more rigorous system, not hoping some better participants show up.

Apart from all the measures which Bernard mentions, there is one that would pretty well eliminate all advantage from pork-barrelling: proportional representation. If all votes were of equal value – because parties got topped-up to their fair share of seats pursuant to the filling of all electoral seats as in NZ – bribing particular voters in marginal seats would be pointless.

I’m not convinced proportional representation would have that result, although it would still be a big improvement on what we have. Bribing voters with big handouts is still a feature of political life in countries with proportional representation. In such countries small parties demand their price before going into coalition with bigger parties who need the numbers to get into government, and that price is often just as corrupt and self-serving as any pork-barrelling seen here.

The root of the problem is political parties. Once they get power they are just mechanisms for generating corruption.

I think that Victor’s final point is due to misunderstanding MME – nothing to do with PR.

With you all the way.

It would reduce the representation of the Nats and increase the Greens numbers. A much better balance.

I could lead to more minority governments but that can be managed.

The idea that we are being governed by a mob with the mindset that thinks they were elected to do whatever they like – to raze the ungodly left to the ground (as some sort of “God’s will”?) – that they were elected by a constituency that knew they would carry on like this – is the most alarming.

How much more damage could they do, if they put what little mind they have left, to it?

How appropriate that I go out on such a topic, the complete failure of our political systems.

This is my second last Crikey. No soapbox claims from me, I think I have just got to the point where knowing all the news doesn’t actually increase my happiness. I’m not making a stand or anything, I’ve been with Crikey from the beginning, back in Stephen Mayne and Hillary Bray days and have enjoyed the stories and more so the conviviality and intelligence of most of the commentary. The term ‘infobesity’ was introduced to me recently. I think I’ve got it.

I wish you all well. I’ve so enjoyed the contributions of older hands like Jack Robertson, the impish humour and asides of zut alors and klewso, the depths of discussions whenever Rundle writes. I’ve particularly enjoyed the contributions from the fairer gender who now grace the forums. There was a time when Crikey’s commentary was a bit of a sausage factory. Shout outs to DilletanteBeth, a great moniker, to Griselda Lamington, how did you come up with that name, Selkie, ratty and many others.

Some of you might not see that I comment often because I’m usually a few days late. I have tended to do this because I’m as much interested in the comments as the story itself.

I’m sure I’ll come back and add lots more commenters names that have made me think, made me laugh or made me cry, well, sort of. Nobody really made me cry.

Take care all. I’ve been Dog’s breakfast for a long time now. Time to find a new skin.

And all the new commenters that have added their thoughts to the forums. Thank you.

And Bushby Jane. Jane has been around on Crikey a fair while.

Thank you.

Thanks for your companionship, it’s been a nice trip on the hole, I’ll miss it – catch you in the dog house.

What a lovely way to ” go out”, DB… Farewell and enjoy your life.

I’m only quite new to Crikey but completely understand that “knowing all the news doesn’t add to (your) happiness”.

I must confess that I find myself in a similar situation, after many many years of subscribing to upwards of ten digital and/or paper news/media, I’ve whittled it down to three.

The way things are going, it won’t be long before it becomes two – in my case, I’ve found that too much news really does contribute to feelings of anger, dismay and often hopelessness.

Life is increasingly too short …so all the very best to you, DB.

i am also fairly new on Crikey comments. Have enjoyed the regulars’contributions. Used to rely on Fairfax papers for some balance but that has now gone, so the only voices are represented by Crikey, and some commentors in NewDaily.

I think you’ve been around a while Marcia, and rarely a cross word spoken if I recall correctly. Maybe not an old hand, but no noob.

And that’s another cheerio, to Been Around. Loved your work BA.

What a lovely letter. Well, the near-total collapse of the MSM (or maybe only my own recent awareness of it!) surely vindicated your decision all that time ago to contribute here and to then consistently do so, and thank you so much for that. No, the news isn’t making us any happier. You won’t be missing anything!

Cheers, Lord Muck. My future problem is keeping my mind active while indulging less in media. Will be a trick to manage that.

I have enjoyed and will miss your comments. Many of you of the “older guard” have an intelligence and knowledge that’s not displayed in the MSM. Enjoy the after Crikey.

Best of luck AC. The comments section is usually where the gold is found. Take that as a tip.

Won’t be the same without you DB!

Cheers Lexus. I always read your comments respectfully, while not always agreeing. Who agrees with anyone all the time though?

You will be missed – always measured, never mean.

Something to which many could aspire.

Thanks one and all. Perhaps there is a thing called ‘community’, or society. Could Maggie Thatcher have been wrong?

Farewell DB. Your thoughts ring true. I’m just a new subscriber, yet the holes in the apartment walls increase daily from the frustrations of Crikey’s revelations. I’d rather punch a politician than lose my daily read.

Stay with it Syd, and keep them on the straight and narrow. Bernard needs the occasional clip over the ear (metaphorically of course) and the editorship can get a bit click-baity, keep them honest.

Really sorry to see you go as have always valued and enjoyed your insights. Wishing you well on your info-diet and have total confidence that something new and valuable will emerge from hanging out in space you are creating.

I shall miss your comment. Always look Soward to reading them.

‘comments’ and ‘forward’.

Let’s call a spade a spade. With all these like-minded, self-serving, arse-covering elites protecting their nice little earners, what chance of any change? Us plebeians are not blameless as we voted them in (albeit a miracle!).

Don’t blame me. Blame Morrison’s “doG”.

Did we vote them in?? If we buy a product that promises youth and it doesn’t deliver did we ‘vote’ for a scam product or fall for a scam??? Australia Institute has a petition for truth in political advertising laws if anyone else wants to sign. I sure do and did! https://nb.australiainstitute.org.au/truth_in_political_advertising_fed

I love the gratuitous insults piled on the Andrews Govt whereas the Lib governments just seem to be disappointing to Bernard.

He has long been Gladys’ biggest, and most shameless, booster and the bane of Labor.

The B in BK does not stand for ‘balance’.