Earlier this week, Prime Minister Scott Morrison made much of announcing an additional $500 million “to support developing countries in our region as they tackle the impacts of climate change”. In particular, this included “an increase for the Pacific from $500 million to at least $700 million”.

While the amount is trivial compared with the $18 billion the government is spending to subsidise coal exports via the inland rail project, and its backing for new coalmines and gas projects, nonetheless the government is proud that its new total of $2 billion “doubles our previous five-year commitment of $1 billion between 2015 and 2020”.

Australia’s climate funding is about adaptation, not mitigation. We’re not interested in actually stopping climate change but we’ll engage in the pretence that we want to help Pacific island communities “adapt” to it, when in cases like Kiribati and Tuvalu, the only long-term adaptation is permanent departure.

A new study by Greenpeace, however, has unmasked just how paltry our commitment even to the self-serving idea of “adaptation” actually is.

Its author, Dr Alex Edney-Browne, Greenpeace Australia’s investigations officer, has forensically examined the list of aid projects funded by Australia and maintained by the OECD, based on information on all bilateral aid funding provided by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, as well as interviewing regional leaders about their experience with climate aid funding.

About 1% of foreign aid between 2016-18 was spent on climate adaptation projects, and in 2018 the government withdrew from the UN Green Climate Fund, claiming it could deliver more outcomes through direct aid.

But as Edney-Browne found, when you actually examine many of the projects, their connection to climate vanishes. The list for 2019, the most recent year — provided by DFAT to the OECD — includes funding for Australian volunteers to teach in schools and provide healthcare in Africa and South-East Asia, programs aimed at gender-based violence in Afghanistan, reproductive healthcare programs in the Middle East, trade support for APEC countries, human rights programs and business development programs.

All these worthy programs are categorised as having a “significant” climate adaptation component despite the lack of any apparent connection. There are a number of programs listed that could be linked, vaguely or more specifically, to climate adaptation — more resilient infrastructure, water supply, agricultural practices, energy projects — but they form a minority on the list.

The list of Australia-funded programs for which climate adaptation was the “principal” component is blank — DFAT hasn’t provided any detail of any such programs and refused to say why — possibly because there are none. The previous year, 2018, saw just $27 million in programs where adaptation was the “principal” component, and $24 million the previous year. Australia’s 2018 “principal” climate adaptation program list included a $5 million family planning program for the Pacific.

One of the more bizarre inclusions in Australia’s list of “significantly focused” climate adaptation programs are multiple programs in Papua New Guinea collectively called a “governance facility”. DFAT reviewed the program in 2019. There is literally not a single mention of climate in the entire 113-page review — except a reference to the “business climate” in PNG.

Australia also counts an “Australia Pacific training coalition” program as part of its “significantly focused” climate adaptation programs — designed to help workers from existentially threatened island states like Kiribati find jobs in “offshore labour markets” — e.g. fruit-picking for Australia’s rapacious horticulture sector.

On Australia’s recent track record, the extra $500 million offered to developing countries is likely to end up simply replacing existing aid across the length of and breadth of Australia’s aid efforts.

We don’t take the prevention of climate change seriously, but nor do we take the self-serving objective of adaptation seriously either — instead, it’s a shell game using existing aid funding.

Pacific Nation(s): As an Australian citizen I am beyond embarrassment. Far beyond. How my government’s duplicity has replaced genuine fellowship, financial support, sufficient to minimize climate threat . . . with deceit. More than deceit. In fact Pacific Nation(s) abandoned to their individual fates. To stand alone with only one certainty. Dispersal. An inevitable outcome facing many peoples over an ever-shortening period. How can this be allowed to happen?

Our benighted government members won’t live long enough to reep the crop they are sowing – which could well be a human wave of refugees fleeing a crisis we abetted with our disastrous promotion of fossil fuels (think Santos at the Australian stand at COP 26).

And apparently they are all sterile and have no children or their children are not going to produce grand children for our so called leaders… and soon and so forth.

Do you really believe “our benighted government members” won’t live beyond nine or 10 or 11 Years?? We are beginning to “reep the crop” NOW!

Less a crop than reaping the whirlwind which our previous actions have sown.

Hi graybul . How can these actions and failures to act be even vaguely in line with any belief in a God ? Does our PM believe as he helps the profiteers and money changers his god will wave his magic wand and all will be well less a 10% tithe ?

There is a direct conflict of interest between Australia’s objectives, increased and sustained use and export of fossil fuels for as long as possible and those of the Pacific nations, having land to live on. What aid we give is doubtless tied to getting them to shut up about climate change and for purchasing Australian goods and services at uncompetitive prices. Hence, not giving it to them through international institutions.

The Pasifika people should be talking to the French and Chinese, both would love to marginalise Australia, have lots of aid money that would be no more tied than what they get from us and in the case of the Chinese, a proven record of building land in the sea.

Or the Dutch – the east of the Zuider Zee is rapidly becoming a wilderness with unexpected species (some previously rare or thought to be extinct in the area, esp water fowl) through landfill, reclamation and fencing off from human depredation.

Having almost half ones landarea below sea level has concentrated the lowlanders’ minds wonderfully for centuries.

Above all AP7 The Libs will protect the fossil fuel lobby and will use the public purse to do so. Free speech will be the next victim

This Coalition Government, especially Scott Morrison like to make BIG funding announcements, but they rarely stack up.

It’s the Coalition’s way of promising funding for something that will go over well with the Public, but in reality is just putting money into slush funds that in a lot of cases are even at cross purposes with the announcement, e.g. Fossil fuel funding

How right you are: ‘in cases like Kiribati and Tuvalu, the only long-term adaptation is permanent departure.’

There’s one other thing we all need – the long-term permanent departure of the fossil-fooled Lib-Nat government, with occasional support from – let me not forget to mention – Labor.

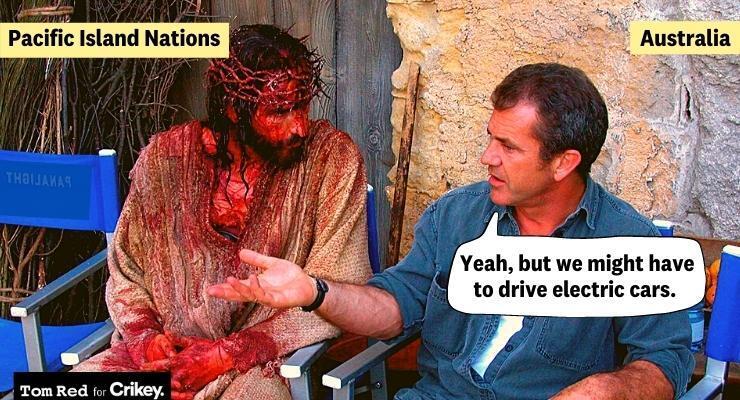

And how can we forget our would be a mutton headed leader in waiting decide the plight of the Pacific Islanders was something joke about

Senior Australian politicians made jokes about the plight of the Pacific Islanders

All of Australia’s coastal cities are going to be underwater, at least the greater part of them. It depends on how much ice we melt, which depends on how dumb we are and for how long – but the signs are not good. There is enough ice to raise sea levels 70 metres, should we melt it all. And now that it has started there is no way to foresee when it will stop. The only help we can give small island nations, in danger of drowning, is to use zero fossil fuels, replant forests, etc. But they look to be stuffed. Perhaps we could give all their people Australian passports and rent assistance if they show up?

The French islands will of course be given submarines. (That’s meant as a cynical sick joke.)

They might be useful as commuter transport, to get all those people to & from their CBDs…oh, wait.

Barely 2.3M live in the endangered, soon to be octopussy garden, islands, which is less than the legal, admitted/acknowledged, migration of the Howard years.