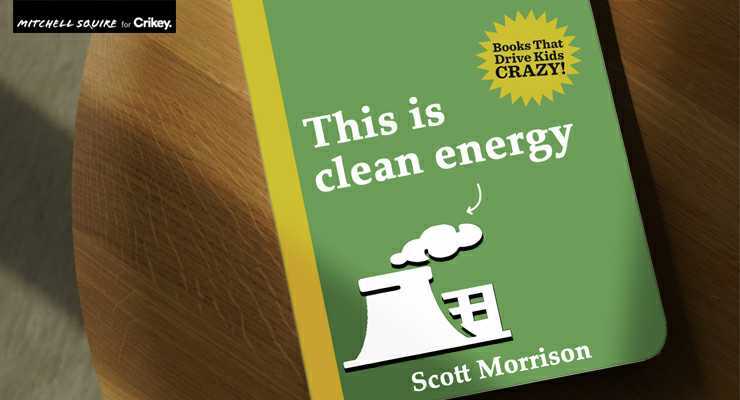

In the aftermath of COP26, and Scott Morrison’s refusal to pursue any climate policy beyond hoping something will turn up, it’s worth revisiting what is, for all its faults, an impressive policy document on pursuing net zero by 2050.

Created by the international peak body for fossil fuel industries, the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 takes a hard look at the policies needed to deliver net zero emissions. And while — unsurprisingly for a fossil fuel lobbyist — it relies on carbon capture and storage to make its numbers add up, CCS contributes only 8% of its projected total global energy demand in 2050 and 2% of electricity supply.

But the other 90+% of the roadmap to 2050 is very different from the policies of the prime minister and his Energy Minister Angus Taylor.

No new coal, oil or gas fields

The IEA says “beyond projects already committed as of 2021, there are no new oil and gas fields approved for development in our pathway, and no new coalmines or mine extensions are required”.

Morrison’s position: approving new and expanded coalmines and gas fields, subsidising new coal and gas exports through infrastructure subsidies, support for massive fossil fuel projects (like Woodside’s criminal Scarborough field development) and funding gas companies’ CCS projects they falsely claim will offset additional CO2 emissions.

Policies to send market signals to drive investment in clean technology

“Mobilising the capital for large‐scale infrastructure calls for closer cooperation between developers, investors, public financial institutions and governments. Reducing risks for investors will be essential to ensure successful and affordable clean energy transitions.”

Morrison’s position: a significant fall in renewables investment since 2018, according to the Clean Energy Council, driven by investor uncertainty; the redirection of renewable energy funding to CCS and pushing for an electricity bill tax to prop up unviable coal and gas-fired power stations.

Whole-of-government net zero policymaking

“Devising cost‐effective national and regional net zero roadmaps demands cooperation among all parts of government that breaks down silos and integrates energy into every country’s policymaking on finance, labour, taxation, transport and industry.”

Morrison’s position: the government’s net zero “plan” relies on as-yet-undevised technologies to deliver 15% emissions reductions, and 10% from discredited international offsets, and proposes no policies to deliver emissions abatement.

No coal-fired power stations by 2030 in developed countries

Morrison’s position: wants coal-fired power to remain part of Australia’s electricity generation into the 2040s, if necessary subsidised by a household electricity tax.

Increase in electric vehicle sales to 60% by 2030

Morrison’s position: after demonising electric vehicles in 2019 as incapable of towing or enabling recreation, his EV policy released in November 2021 aims for 30% of vehicles sales to be EVs in 2030. Critics point out Australia’s emission standards mitigate against EV sales here and Morrison’s policy fails to address the high cost of EVs.

End to sales of internal combustion engine vehicles in 2035

Morrison’s position: the government has ruled out ending sales of fossil fuel-based vehicles, boasting that it believes in “can-do capitalism” not “don’t-do governments”.

All new buildings are zero-carbon-ready by 2030, 50% of all buildings retrofitted to net zero by 2040

This is a crucial part of the path to net zero and one we hear virtually nothing about — especially the task of retrofitting existing buildings.

Last week NSW Planning Minister Rob Stokes announced that all new large commercial buildings will be required to be net zero from next year, as well as mandating the end of dark roofs on houses.

Building standards are a matter for the states, but the Morrison government has the Australian Buildings Code Board that reports to state and federal ministers, housed in Taylor’s Industry Department. The ABCB is “investigating” net zero requirements for its 2022 code, but refuses to commit on the basis that “some would say this is too ambitious”. As usual, NSW is racing far ahead of the Commonwealth.

The task of retrofitting building stock is daunting but also represents a potentially massive and persistent economic and employment stimulus, with additional construction and renovation work required for decades to shift existing, often carbon-intensive commercial and housing stock to net zero (the IEA assumes 85% of all housing stock will be net zero ready by 2050).

A smart, ambitious government would spot the employment and investment positives of the mammoth long-term project, which won’t be magicked away by Morrison and Taylor’s nonsense plan, but will require investment, employment and coordination across the country — perhaps even leadership.

But that’s been left to state governments like NSW that aren’t afraid to lead and understand the economic benefits of net zero.

Blah! Scarborough! Blah! 3°+ on the way. Natural gas is simply methane, and enough of it leaks along the way (3%) to make it equal to, or worse than, coal. In light of known facts, Scarborough is a crime against humanity, and against the planet. Oh well, mustn’t grumble.

The LNP, many Australians and Australian companies will not have a choice as global industry, including competitors, adopt non fossil fuel futures and trading partners follow suit e.g. EU’s mooted carbon tariffs (that will flow through supply chains).

Meanwhile majority of ‘quiet’ Australians follow climate science but will (apparently) not support any financial penalties or modest costs being attached to carbon.

This inertia encouraged by political media includes ‘greenwashing’ fossil fuels, avoiding innovation and responsibilities, by blaming immigration and population growth through an astroturfed Malthusian ZPG lens, how smart or selfish are we?

Re: “End to sales of internal combustion engine vehicles in 2035″…

The world’s primary industries need a guaranteed supply of fuel for their various internal combustion engines. Whereas a minesite can be electrified, fishing boats etc can not. In the absence of diesel, they need synthetic fuels. A global initiative is required for large-scale capture and hydrogenation of atmospheric carbon in the synthesis of fossil-free liquid fuels.

With the advent of solid state, low temp, low pressure hydrogen storage, I think cars and boats will eventually use fuel cell powered electric motors. In this area it almost doesn’t matter what the govt decides, as the market will dictate the outcome. Kandi will release the first under US$10,000 EV next year in America, I think the Chinese EV onslaught will then begin in earnest in the rest of the world. By the 2030s no sane company will be producing ice cars anymore.

Hi Bref, you may just be right about primary industry evolving towards “fuel cell powered electric motors”. However the eventual advent of “low-pressure hydrogen storage” may well involve an intermediate liquid (such as ammonia?). In turn, the gasoline industry would have to evolve to supply it, a fossil-free liquid fuel.