Note: the following story contains references to suicide and sexual abuse.

It was 4.43pm on September 2 when Andrew called. The precise time matters because of what he had to say and what happened in the next 90 minutes.

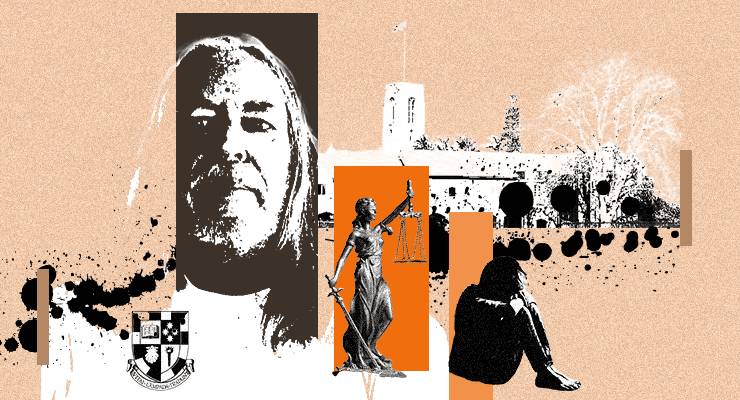

Andrew Coffey is his name. He’s brave to use it because he has been through the mill and he was about to expose it all in detail. He insisted that what he was about to say should be recorded and then given to the ABC’s 7.30. His reasons will become clear.

Coffey was raving. What I didn’t know was that he had driven to a headland and was sitting alone with a canister of petrol beside him. He also had a lighter.

There were several targets for his rage, insurance companies prominent among them. But when you boiled it down it was the system: being passed from department to department by employees of huge organisations that are meant to care, but don’t, and transferring your call to people who don’t know anything about you and your case — which you then have to explain, over and over.

It was about 10 minutes into the call that Coffey declared he’d had enough. When night fell, as he sat watching the ocean, he would douse himself with petrol and end it all.

I had a hunch that the best thing to do was to keep him talking. Maybe he would calm down. See reason. Andrew? Andrew?

Silence. He was gone.

There are two heroes in this short 90 minutes of life. One is Coffey for having made it to the age of 62 given what he says happened to him at the age of 14. The other is the New South Wales police officer who got to him fast and talked him down before darkness fell. There were minutes in it.

I found out the next day when he sent a message to say sorry and thanks. He had been taken to hospital and later released into the care of his family.

It turns out Coffey was well into his plan when he saw torchlights coming up the hill to the headland. He was persuaded to drop what he was doing and to walk away before an officer brought him to the ground.

“I even failed at killing myself,” he says ruefully now.

It was not the first time Andrew’s tried to take his life. This time though he had felt something new.

“Right at the end I thought I wanted to be alive.”

The ordeal is far from over

Andrew Coffey’s is a voice from the void.

If you assumed the ordeal for child sex abuse victims somehow ended with the McClellan Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse set up by prime minister Julia Gillard in 2013, Coffey’s case is proof of how wrong that is.

His story demonstrates how hard it continues to be to seek justice through the legal system where non-disclosure agreements act as a key bargaining chip for institutions. It is also, ultimately, the story of how a few good people acting out of genuine goodwill and the Christian values they espouse can make a big difference to a broken life.

The royal commission hearings acted as a daily reminder for Coffey of what he says happened to him in 1974 when he was a student at Sydney Church of England Grammar School, better known as Shore. They also made some sense of the horror of Coffey’s life. In 2018, more than four decades on, he took himself to the police and disclosed what had happened: he had crossed paths with a science teacher named Colin Fearon who, he said, abused him.

Coffey was gripped by a need to find out everything he could about Fearon. He pursued freedom of information requests through the police. He also came across a report I had done on Fearon for the ABC’s 7.30 Report years earlier — which is why he got in touch with me.

I suggested he get a lawyer, ASAP, the first step in seeking justice. It also meant Coffey’s life was about to enter a new hell — though perhaps one which might ultimately bring some resolution.

Shore’s insurers call in Pell’s man

Shore is one of Australia’s wealthiest schools with playing fields and facilities fit for princes. It also promotes itself as a bastion of Christian values. But when Coffey’s complaint arrived it followed a godless protocol: the school, which takes in about $75 million a year in fees and government funds, on top of assets worth more than $500 million, handed the issue to the insurance company for the school’s titular owner, the Anglican archdiocese of Sydney.

Shore’s insurers appointed lawyer John Dalzell, whose name is linked with the so-called Ellis defence which the Catholic Church under then-Sydney archbishop George Pell had used with devastating effect on victims of child sex abuse.

Dalzell, now with Dentons lawyers, was then with Corrs Westgarth, the legal firm retained and instructed by the Catholic Church. The church made the case that there was no legal entity that could be held responsible for the actions of its clergy which meant there was no entity a victim could sue.

Legally it worked a treat. But the church abandoned the defence in 2019 after the royal commission.

From Coffey’s point of view, Shore was sending a signal: “Why Shore School and presumably the Church of England would think it a good idea to appoint Dalzell — given his past history — beggars belief. Whatever their reason, I interpret this as an aggressive step by the school and church, which is not what I had hoped for.”

Shore has declined Crikey’s request for comment on the appointment of Dalzell.

Andrew Coffey’s alleged abuser was a teacher with a history. He had fled New Zealand, with NZ police investigating allegations that he had abused boys when he was a teacher at a high school in Christchurch. Yet he somehow found his way onto the staff of the exclusive Shore school.

Tomorrow: A dangerous paedophile and the case against Shore.

For anyone seeking help, Lifeline is on 13 11 14 and Beyond Blue is 1300 22 4636. In an emergency, call 000.

Survivors of abuse can find support by calling Bravehearts at 1800 272 831 or the Blue Knot Foundation at 1300 657 380. The Kids Helpline is 1800 55 1800.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault or violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au.

Every survivor is a hero. The churches and their schools push back against all abuse claims in the hope that the matter will be delayed and never get to court. Taxpayers should not be funding organisations that shelter sex offenders.

The public sector is rife with bullies. So as long as it’s not sexual offences it’s ok for tax payers to fund it?

No it certainly is not

Laser focussed, dense and economically short. Gutsy stuff naming names. It makes the pain and lifelong torment starkly real. Kudos Mr Hardaker.

And no-one is talking about the plight of victims of child sex abuse in the prison system. I think people would be shocked if they knew how many men who end up in prison are victims of childhood sexual abuse, institutional and family. It is hard enough getting compensation for prisoners who were victims of institutional sexual abuse. If they were victims of an individual, either family or stranger, and if (very big if) the person was ever charged and found guilty of the crime, then prisoners have to go through the state victim compensation scheme. And that is really, really hard because many of them have a character test. Imagine having to convince a tribunal that the magnitude of the crime done to you as a child outweighs anything criminal you’ve done as an adult. Imagine having to make that comparison, especially in the knowledge that your offending was highly likely to be an outcome of the abuse.

One of the things that is not being talked about is how abused men are ending up in the same prisons as their abusers. This happens because so many historical child sex abuse cases are coming before the courts. There are a significant number of old men in jail, which is a problem all of its own. Coordinating prisoner movements so they are not in the same area as their former abuser is a bit of a headache.

BTW – next time you think it’s hilarious, to joke in any way, shape or form about men being raped in jail, just don’t. It is not funny and it’s not fair justice or karma or whatever people think it is. I’ve worked with men who have been raped in jail. Quite often they were victims of childhood sexual abuse. They are broken men. Don’t joke about it, and pull other people up when they joke about it. If we all start doing that, people might get the message that rape is never a joke, no matter the circumstances.

The Justice system is as much of an offender as anyone inside in my view. Each one of us that votes has had tougher on crime promises thrown at us, whilst the dream of rehabilitation coupled with support during incarceration helping offenders to reach better lives remains just that. I would never joke about someone behind bars – you never know their own back story. I wish them all well.

The Royal Commission gave us survivors hope that the pain would end.

The fact is it gave us false hope that perhaps empathy for our position would come into being and that the church’s would change – but nothing occurred .

Families still victim blame and believe it was just a few bad eggs in the church that did this

And caused even more relationship breakdowns and ostracism by bigoted families

The ritualistic abuse, hazing, violence, sometimes sexual, intimidation, vilification, humiliation. Those were the days. Called just another day as a junior at a GPS school. And that was just what the seniors did.

The teaching staff. Ha. Yeah nah.

Then 1980 happened.

After that, when I got to senior, we were told that if we, as seniors, did any of the above, as we received, the matter would be referred to the police.

Even the town pedo was locked up. Which meant no more easy pocket money ripping him off.

You lived in such a lucky town if it all ended. For the rest of Australia, the most senior executives of every religion, sect and cult were happily hiding and protecting paedophiles until much later than that. Even now, some executives of the church of Rome are bellowing for the right to hide (and thus condone) serious crime within the ranks of their own organisation.

Mine was a non denominational grammar school. The local private tyke school, for cattletics, had it bad, but we were jealous because they were co-ed. The prep school boys got a touching though including some lads in my class. I think the main pedo at prep went to jail about 2000.

…. but He loves you..